A 1919 British government report on Adult Education had this to say about the changing nature of modern society: ‘Where modern industry has multiplied the commodities within reach of the consumer, it has undoubtedly lost many of the humanizing and educative features which were characteristic of the earlier economic organisation.’[1]

Inadvertently perhaps, the insight is an early recognition that technical and cultural or moral progress do not necessarily move in tandem. The loss of ‘humanizing and educative features’ also seems to be an apt description of contemporary education in the Anglo–American world. Like commodities, qualifications multiply; governments monitor their nation’s position in international comparative league tables; they are keen to proffer statistical evidence to show the success of their existing educational policies, or to justify new ones guaranteed to raise educational performance. Two questions arise:

1) Is qualification the same as education, or to what extent are they synonymous?

2) While the acquisition of knowledge is undoubtedly central to education, is it the sum total of it?

Qualification Versus Education

The strength of connection between qualification and education is historically contingent. In large part it depends on societal and cultural attitudes towards knowledge, and the extent to which canonical knowledge is understood and valued as something distinct from, although related to, every day, informal knowledge. More specifically, it depends on whether exam boards and educational professional bodies, teacher education departments, and publishers recognize and value the distinction because, collectively, they produce exam papers, attendant guidance, supplementary material and labyrinthine mark schemes, which teachers are expected to use. Exam papers are limited in what they can assess, and in a subject like English, the internal transformations in pupils’ responses are unlikely to be fully accessible to examination.

But there are better and worse types of questions. The traditional essay-based question used in Britain until the education reforms and reorganization of existing exam boards from 1988 differed from the psychometric-based testing used in the American education system.[2] However, soon after the reorganization of exam boards, the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (UCLES), in the process of amalgamating to become OCR, introduced psychometric testing units within their Research and Development Division. The effects on the quality of examinations have been dubious at best.

The De-Humanizing of Literature

If we accept that the study of English—either as a course in language or literature—belongs to the Humanities and/or Arts, then at the very least we should expect to see exams that seek evidence of pupils being familiar with interpretative complexity, able to make reasoned inferences, and having an ability to express an individual personal understanding in more formal, public language. In this aesthetic paradigm of English, the features of language that can be separated out as techniques, grammar or literary devices, for example, are reconnected with their core function which is to convey and modulate readers’ responses, internal and in their external articulation. In other words, contrary to a common misconception among the education profession, knowledge of the text is not antithetical to a Leaviste experience of the text, although sequencing of lessons is important.

It is very possible to dampen pupil’s motivation to engage fully with what they are reading by introducing too much contextual or technical information too early. Matthew Arnold made this very criticism of the teaching of Classical texts (which would have been in Latin) in his general reports as a government school inspector between 1867–1871. His complaint was that too often the annotations and historical notes were longer than the text itself. For Arnold the priority being given to linguistic techniques and factual information was hindering a proper engagement with the moral content or wisdom encapsulated in the Classics. However, there are different ways to obstruct a proper moral and aesthetic engagement with literature. The example below, from one of Britain’s major exam boards, OCR, shows the importance of framing questions and instructional language in exams.

‘The cultural value…is not on the humanizing dimension of reading literature, but on its more technical analysis where the art of judgment has little place’

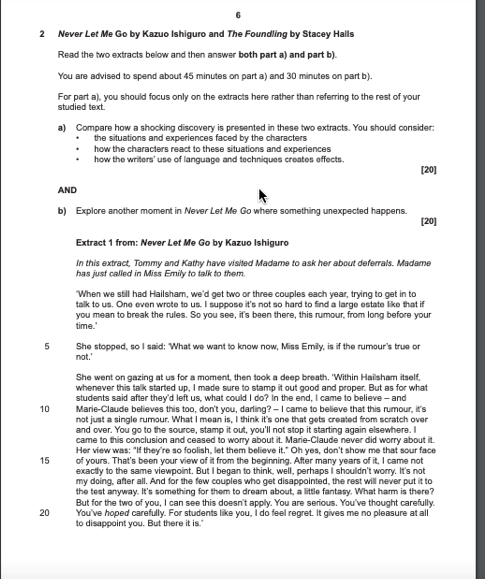

The example is from OCR’s 2023 English Literature paper: J352/01 — Exploring Modern and Literary Heritage Texts, and the question is on Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Never Let Me Go. The novel’s themes offer rich content for engaging with moral questions about what is unique about humans, the extent to which non-humans (or in this case clones) can be human, and the narrative plotting is complex and echoes, to some extent, the ‘movements’ of memory, and his writing is masterful in building suspense and slow dread. With such emotionally and intellectually rich content the exam question directs pupils’ attention to the technical presentation of a shocking discovery (that deferrals, a chance for a clone to live, are only rumours). The question in Section B is extemely general and encourages a generic search for ‘something unexpected’ rather than deeper understanding of universal themes or practising moral judgments vicariously through literature.

The exam paper encourages either a technical analytical approach, or an over-general response based on a personal opinion or feeling. The type of traditional essay-based question, which would require extensive knowledge of, or engagement with, the text as a whole, including its major themes and characters and a judgment, is largely missing. Of course, this doesn’t mean that richer classroom discussions have not been provided, but it indicates that the cultural value, what counts officially, is not on the humanizing dimension of reading literature, but on its more technical analysis where the art of judgment has little place.

If we compare the 2023 example with a question from a traditional essay-based question from an UCLES O Level paper, bearing in mind O Levels were taken by pupils deemed to be most academically able, the difference becomes clear to see: ‘“Inside the house [The Radley Place] lived a malevolent phantom”, writes Harper Lee in the first chapter of the book. Explain briefly how Boo Radley had acquired this reputation, and then referring closely to the part he plays in the novel as a whole, say how far you think he deserves to be called “malevolent”’ (Question 19 from Section B of UCLES English Literature O Level Paper, 1971, based on To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee).

The question requires both substantive knowledge of the narrative as a whole and a personal judgment grounded in the text, not individual opinion or feeling alone. The reduction of intellectual demand can be reasonably inferred by comparing the changes in the instructional language. The questions in the 1971 paper included the following:

- Illustrate

- Show that

- In what ways

- Explain

- Make clear

- By referring in detail to…say how far you think that…

- Describe

- Give a brief account of

- State simply

- Give in your own words

- How would you express in modern English

The 2023 paper, by contrast, uses a far more restricted range of instructions, limited mainly to ‘compare’ and ‘explore’. This reduction could be presented as a positive development offering greater systematicity, generalizability, more equal access for pupils whose prior cultural and linguistic capital is less advantaged than some of their more middle-class peers. Whatever the intentions, the attempt to apply methods of psychology and seek generalizability that characterizes scientific knowledge has resulted in the weakening of what is unique to both literature as a form of knowledge in the Humanities, as well the specific imaginative and intellectual riches of specific books. While individual teachers may find ways of incorporating the more practical criticism approach of Leavis, who contributed to writing exams for grammar schools, we can infer from the above that there has been a social demotion of the humanistic heart of literature. Exam boards, after all, provide paper to be taken by almost all the young generation, not only those continuing to higher education. So, sociologically, they represent a society’s most general, official models of knowledge and education.

Furthermore, this has been accompanied by a similar demotion of the status of the teacher. This much is indicated in the quantity and quality of mark schemes, guidance, Assessment Objectives, where a historical comparison is telling. Before the reforms of the1980s, teachers would get little by way of guidance, supporting documents for the syllabus. The examiners’ report would be the main source of guidance for teachers regarding the more or less successful aspects of teaching they gleaned through their marking and moderating papers. The following is from the UCLEs Examiners’ Report of 1957 which stated the aims of the syllabus for the pupil were ‘to discover what reading (in its fullest sense, with enjoyment and understanding) can mean, to widen the range of what he (sic) can read, and to give him the opportunity of developing a sense of discrimination and a vocabulary which will allow him to formulate his own response to what he reads.’[3]

An OCR short statement of aims from its 2009 Specifications for GCSE English Literature states:

‘The GCSE English Literature specification has been designed to be enjoyable and inspiring and to allow you to make the most of your passion for literature. It provides good links to further study for your learners.

The English Literature specification comes with a large range of set texts designed to suit a variety of learners. We want to help you bring the wonderful power of English Literature into your learners’ lives, and this is reflected in the texts we have chosen.

There is a flexible and practical choice of poetry assessment in this specification. In the examination there is a choice between answering a question on a previously studied or an unseen poem. You and your learners can choose the best way for them to address this question.’

The latter has the hyperbolic tone of an advert: it posits the study of English Literature as a commodity to be enjoyed or used instrumentally; and it embeds a wholly static and passive model of the reader. Absent are any idea of developing a deeper response or sense of discrimination. If we are concerned with the flattening and coarsening of public language and discourse, we couldn’t do better than to start addressing the problem here.

The intellectual and imaginative evisceration of English Literature through framing it according to principles from science, a form of knowledge whose object of study is the material external world, not human subjectivity or moral thinking, also affects curricula at the level of higher education. In part this arises from the development of modern secular universities such as Berlin’s Humboldt University, established in 1809, in the wake of the philosophical revolution of the Enlightenment. Humboldt, inspired by his reading of Kant’s work, established the institution to provide courses organized along principles of scientific rationality. The focus of knowledge shifted from transmission of past canonical knowledge, to be studied for pursuit of metaphysical truth and virtues such as wisdom, towards producing new knowledge to better grasp the modern world and the changes in social and individual life it introduced. Sociology and psychology were, in part, the result of such a change in intellectual and ethical orientation.

‘Should education be organized according to theoretical principles derived from science, or the ethical orientation of the Humanities?’

Science came to be regarded as better, not only for its applicability to technical problems, but also as it lacked the cultural elitism thought by some to inhere in the Humanities. This, essentially, was the nub of public debates between Matthew Arnold and the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley: should education be organized according to theoretical principles derived from science, or the ethical orientation of the Humanities? The two aims can, of course, be held in productive tension, but there are political, cultural and intellectual preconditions for that possibility which, increasingly, became weaker.

Over time, especially scientific knowledge, combined with an emerging class of industrial capitalists, proved capable of improving material conditions for many as well as profits for the few. This lent scientific knowledge an aura of being a superior form of knowledge, one capable of providing organizing principles for all manner of human endeavours beyond its immediate remit, including education itself. In the early 20th century, Ernst Cassirer was not the only thinker to warn that society stood to lose a great deal if we persisted in conceiving of scientific knowledge not only as the best form of knowledge, but the only form.[4]

One important contemporary development within academia, related to these longer-term changes, is the inflation of the role of research as opposed to traditional scholarship. A theoretically narrow and chronologically truncated idea of research is often regarded as the main substance of any academic inquiry, rather than one part of it; and a part which is supposed to test hypotheses derived primarily from wider and deeper reading within the particular, and cognate, fields of knowledge. Pierre Bourdieu is critical of the situation in French academia where study was pushed into either hyper-empiricism ‘drowned in data’, or theoretical formalism; neither of which are adequate for capturing, or at least better approximating, social reality.[5] He laments the state of knowledge in his discipline: ‘Sociological practice is more and more confounded with computer work, with exercises in game theory, which rest on the hypothesis that one can, by setting out from formal principles, deduce behaviours, groups of behaviours or the organizational forms of social reality.’

He rails against intellectuals who too cavalierly exempt the study of persons from being an object of scientific study. He proposes that anything can be an object of science, and if there are particular difficulties, then ‘particular must be found to overcome them’. It is important to note that he is not describing empirical reality, ie suggesting for example, that education or knowledge itself are themselves scientific phenomena. Rather he is making an epistemological point that anything from social reality can be studied scientifically or systematically: nothing should be out of bounds. But a social fact differs from a fact of nature: in the social sciences there has to be a prior act of theoretical construction of, or apprehending, the object of inquiry. From this a model can be developed, but not ‘a formal model destined to be a void, rather a model intended to be matched against reality.’ We can extend his formulation to ask of our current and past models of English Literature as evinced in past and present exam papers, which better matches not so much social reality, but the reality of literature and the reality and richness of human subjectivity.

To conclude, there have been some strong criticisms of the loss of Humanities at the empirical level, as in courses closing down, but we also need to attend to the internal reconfiguration of knowledge in the Humanities and Arts in which their aesthetic and moral dimensions are shorn, leaving only technique or unreasoned emotion as their main principles of their framing.

[1] Ministry of Reconstruction, Final Report: to Consider the Provision for and Possibilities of Adult Education (other than technical or vocational) in Great Britain and to Make Recommendations, HMSO, London, 1919.

[2] Sandra Raban, Examining the World: a History of the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2008.

[3] University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate, 1971, 5.

[4] Ernst Cassirer, The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, vol. III, the Phenomenology of Knowledge, Yale University Press, 1957 [1929].

[5] Pierre Bourdieu, ‘Thinking About Limits’, Theory, Culture and Society, 9, 1992.

Related articles: