Historical vantages are tricky places to climb. One simply too easily believes that one has reached the summit and has a good view of what is beneath. However, the past is elusive, more like a mirage than a solid kaleidoscope of things that is always fixed in place.

We are, perhaps, almost at a vantage point from where we can look at the socialist regimes of Eastern Europe. The young generation does not carry that much personal baggage concerning these regimes to feel either nostalgic or resentful about them; and they are slowly dissipating into history, seeming like an age which is surprisingly interesting but at the same time a bit odd and antique for generations who open their textbooks for the first time at the Cold War in 2025.

But what does this point of vantage mean? One can only hope that it is more about correct understanding than the calcification of popular myths and misunderstandings.

One point in case—both regarding the growing distance and the usefulness of looking back from a correct vantage point—is the feared interior security organ of one of the most typical Socialist republics, the East German Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, that is, Stasi in popular parlance and MfS for the lovers of acronyms, which was founded 75 years ago today, on 8 February 1950. While every socialist security service was notorious in its own way, Stasi served as a case in point. The East German state merged the cultist zeal of Bolshevism with the administrative prowess of German statecraft. Its founder and longtime leader, Erich Mielke, personified the organization. He led the service only from 1957, but he was the embodiment of his brainchild. He was ever-suspecting. Mielke had a file on the whole leadership of the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands—SED. He was also pathologically pedant, to the extent that his personnel had a drawing of how his lunch and office table needed to be set up, keeping tabs on the last napkin, pepper pot, and the number of pencils. The attention to detail and the setting of complicated rules became the tool of ruthless oppression.

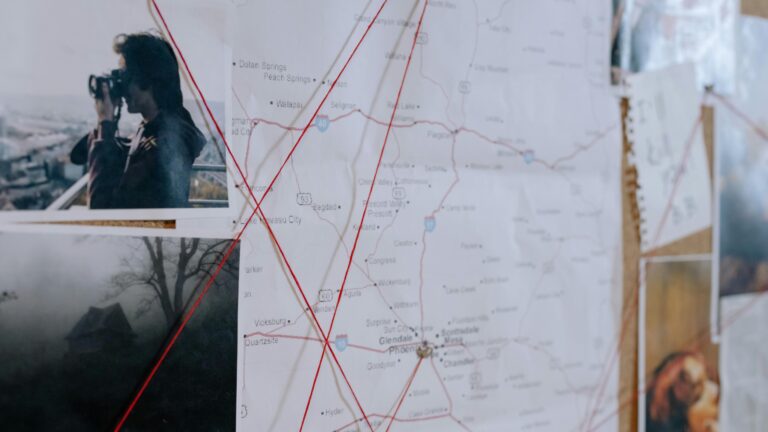

The Ministry of Security, like other Eastern European services, kept a tab on almost every workspace and its ‘characters of interest’ through the pervasive use of civilian informants. ‘Anti-state activity’ was not necessarily stifled with apparent repression; the ‘black car’ did not necessarily come for ‘wrongdoers’, but they were relentlessly bullied into submission by making the everyday life of them and their families unbearable, which could range from usual nastiness like denying a wage raise, a work or university application to the stalking and small attacks on the intimate life of the subject. And the crime? Sometimes, it is just ‘ideological subversion’, an elastic term invented by Mielke himself. East Germany was pathologically dreading not only the present but the potential future threats. Thus, dissent was choked in the crib, so to speak. With it, the soul and spirit of the East German people, too.

‘The Stasi is a warning sign of not only invasive ideologies but the sinister nature of our worst instincts to control and subjugate others’

What is more, the Stasi was not the necessary outcome of Soviet conquest and oppression. This is not to say that Moscow’s rule was not inevitably bad: the Russian plunder, the forced isolation from the West, and the externally imposed communist regimes together could produce good outcomes in neither Eastern European country. Still, the GDR excelled in making the ‘perfect’ police state much harsher than some of its companions in distress—for instance, Hungary. The instincts of radicalism made the GDR even push back against its overlord when the Soviet Union finally started its long reformation of perestroika and glasnost, openness and democracy. Through the course of 1987–88, there was rhetorical pushback and even the banning of some Soviet news materials over the excessive openness of Moscow. Central Europe was conquered and subjugated by the Soviets—but the region crafted its own version of repression and Bolshevik radicalism.

The Stasi is consequently a warning sign of not only invasive ideologies but the sinister nature of our worst instincts to control and subjugate others bureaucratically. The East German repression, institutionalized 75 years ago and already gone decades ago, embodies the power of bureaucracies and the pervasive wish of the modern technocracy, the managerial state, to make its subjects rationally controllable. That it could be born in our region means that we need to look inside and pay attention to the urge of bureaucratic control that we need to have a stable and organized society, which can also roam free and cripple whole communities.

The story of the Stasi was a dead end in Central European history, but at the same time, a warning about the self-serving qualities of the bureaucratic state. As modern industrial civilisation is slowly maturing and searching for new paths of innovation, like information technology, we should take heed of the lessons of past failures of tyrannies to lead a better life in the 21st century.

Related articles: