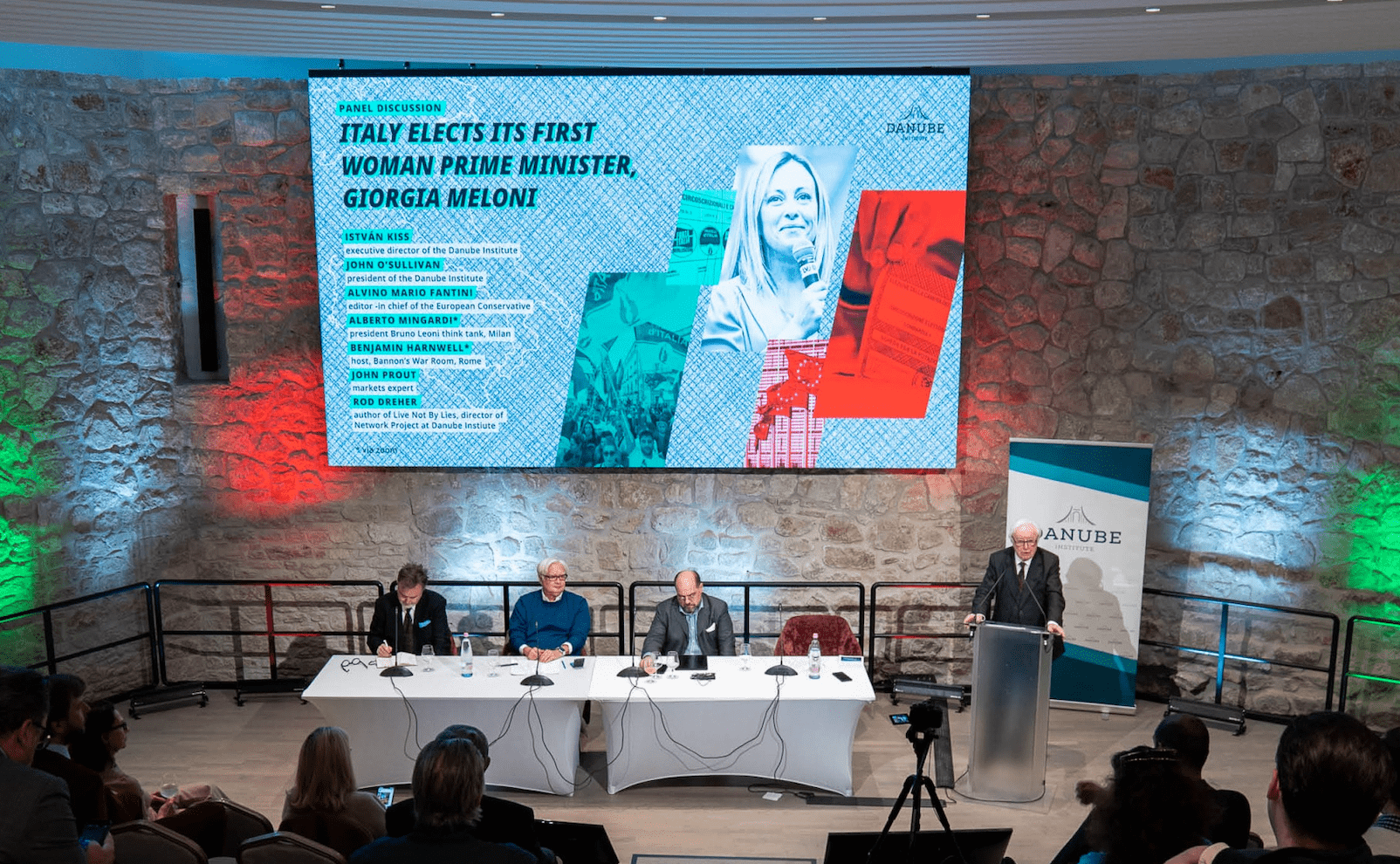

The Danube Institute Event was organised at the Golden Bastion Restaurant, located at a breathtakingly beautiful spot in the Buda Castle. The panel discussion looking at the repercussions of the FdI win in Italy’s elections was held in the auditorium of the restaurant, with some of the commentators joining via Zoom. Commentators included John O’Sullivan, President of the Danube Institute; Alvino Mario Fantini, Editor-in-Chief of the European Conservative; Alberto Mingardi, President of the Bruno Leoni Think Tank, Milan; Benjamin Harnwell, Host, Bannon’s War Room, Rome; John Prout, markets expert; Rod Dreher, Author of Live Not by Lies, Director of Network Project at the Danube Institute; and István Kiss, Executive Director of the Danube Institute.

Disruptive Conservatism

Alvino Mario Fantini opened the discussion with remarks about the growth of ‘disruptive conservatism’. He emphasised that such conservatism has nothing to do with the Tory Party, but rather characterises Meloni, ‘a real conservative’ who symbolises what can be achieved with the tools at disposal. He argued that Meloni represents the conservatism that Europe needs today. In Fantini’s opinion, politics are no longer divided between left and right, but the dividing line is rather between the managerial elites and hard-working, regular people.

Fantini emphasised the need for coalition-building, underlining that the Italian elections saw an unprecedented convergence of different sectors were represented—academics, politicians, leaders, and the common folk were all getting along, agreeing on the same ideas. He added that supporting one another was increasingly important in our world today—not only supporting those around us, but also those beyond our borders—, and that we need to build cross-border alliances and conservative coalitions that go across country borders. Fantini said Hungary is a great leader in this movement, as it is already building alliances with foreign conservative politicians and nations. However, he added that there is still more to be done. ‘Coalitions cannot be about one’s own goals, they have to focus on the greater, common good. As cliché as it sounds, I still believe that the more you do for others and the less you do for yourself, the better off we will all be,’ he remarked.

There is great enthusiasm for this new movement of alliance-building as conservative people around the world and in Europe begin to realise that they are not working in isolation. Many people in conservative countries still work alone, isolated in their foxholes, unaware that they have a ton of supporters all over Europe. Many of those who would actively fight for conservative values and join a coalition are also afraid to step into the light. Since the media paints a threatening image of those who speak their mind, they fear retaliation. Fantini stressed that Disruptive conservatism is not fascism, even though the media loves to describe it as such. ‘We need to help each other as friends and allies and learn from our mistakes. This is not a sprint—this is a relay race where we pass the baton, and Meloni knows this,’ Fantini added.

A Rundown on the Election, and the Future of the Government

Alberto Mingardi spoke about the numbers behind the elections and a shift in voting patterns in Italy. He pointed out that with a staggering 26 per cent of the votes, Meloni began to change the equilibrium of right-wing voters. She differs from Salvini in two ways, Mingardi noted. First, in that she has been in opposition since 2011, and her party has not joined any government coalition in the past decade. Second, at the start of the campaign she established herself as a serious leader, unlike most, more weightless Italian candidates. Mingardi also added that since 2018, Meloni’s voter base has changed drastically, and her situation is changing as well. She represented national conservatism even before it became popular in other countries. Her voters come from different backgrounds but represent and believe in the same ideals. As the elections were dominated by the budget deficit and the ghost of the coming energy price rises, she campaigned using ideas that appeal to the ‘median’ voters as well who could swing the election.

She needs to ‘put her own signature down on the table’, as she faces strong opposition from Salvini

Mingardi emphasised that the increase from 4 to 26 per cent in just four years is extreme, however, it puts Meloni in a difficult position. Mingardi believes that she must do something now to leave her mark on Italian politics, because if she governs neutrally, she will not be able to consolidate her own party. She needs to ‘put her own signature down on the table’, as she faces strong opposition from Salvini, a leader similar to her. Mingardi also underlined that Meloni’s decisions will largely be defined by the government team she sets up in office. Among them, the three most important persons will be the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of the Interior, and, perhaps the most important, the Minister of Economy, who, according to Mingardi, should be someone whom Europe and the market can appreciate, but at the same time someone who is does not want to align themselves with ‘what was before’. He added that he could think of about two or three people in the country who could do that. To close his statement, Mingardi remarked that Meloni’s victory was spectacular, and it is apparent that she is growing as a politician, however, to see her path laid out we all need to wait a few weeks.

British Influence and Finances

Benjamin Harnwell answered a previously mentioned question about Meloni and British conservatism. Before he spoke, members of the panel discussed news about Ms Meloni liking and following Roger Scruton’s ideas, posing the question of how much his philosophy might affect Meloni’s governance. Harnwell expressed a firm opinion on the matter, simply saying, ‘I hope it won’t affect her’. He went on to say that he believed that British conservatism was now ‘dead and should be buried’, stressing that, in his opinion, British conservative politics was currently a ‘disaster’ as true British conservatism had ended with Margaret Thatcher.

Harnwell also added that, to put it simply, Meloni was elected because she seemed the most humane of all the candidates. Authenticity is back in politics, which is indicated by the fact that she was the only candidate that came out of the elections with her head held high. Harnwell also reflected on what Fantini had said about the dividing line between the right and the left: he thinks these terms are ancient and already debunked as they come from the French Revolution. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, referring to the left or the right as political categories is nonsense—these terms are no longer applicable.

Following Harnwell’s statement, John Prout dissected the economics of the European Central Bank selling and buying bonds from different European countries—for example, buying weak bonds and financing them with high-quality German bonds. He added that if politics are right in European countries, this instrument can and will be utilised effectively.

Reception on the West—Journalism Internationally

Rod Dreher began his statement by explaining that he had been ‘bouncing around’ between Europe and the United States for a year and a half. He said he had learnt a great deal about his own profession, journalism, and how different it is in certain countries of the world. According to him, the American media does not exist to write news, but to reinforce an already existing narrative on a given topic—similarly to what the opposition media is doing in Hungary with Orbán’s government. American media outlets did the same to Meloni as they did to Orbán after the elections. As Dreher put it, interestingly, the only media that started reporting ‘Oh my God, lights are going out in Europe’ and ‘Fascism is returning’, were American sources. In Italy, there were no such commentaries in the media, as they do not follow these narratives. Dreher also explained that he thinks social media is a great tool in these times, as one does not have to believe what the mainstream media outlets is feeding them when it comes to certain sensitive topics. He added that social media platforms help debunk regular reports, since if someone knows where to find them, they can go directly to the source to find information on the topic.

Dreher continued by recalling the time when Viktor Orbán said that ‘things won’t change’ with regard to Hungary or Poland, until a core European country goes to the right’—’this has just happened,’ remarked Dreher, adding that over a hundred million people are governed by those who ‘give Ursula von der Leyen indigestion’. He then referred to what Fantini spoke about, the need for a cross-border conservative coalition. According to Dreher, conservatives need to work harder for an international union. Conferences held with conservatives from different countries are needed, like the MCC Budapest Summit that was recently organised by Mathias Corvinus Collegium, bringing together conservative thinkers from all around the globe. He said that the European right must follow in Hungary’s footsteps and reach out to others. Bringing other intellectuals to their own country and conversations that go beyond the media narrative are important in the process of building networks of understanding and support at once.

He emphasised that both Meloni and Orbán are now fighting culture wars. In Dreher’s opinion, both politicians represent what is the popular view on migration at the moment, but others lack the courage to take that upon themselves. They are scared of antagonising the business world. By contrast, Meloni has made it clear that she will not let big businesses have an influence on cultural issues in her country. Dreher concluded by adding that ‘while we have people on our side, we have to show them that these ideas can be embraced—Meloni showed that these ideals can win and be popular at the same time.’