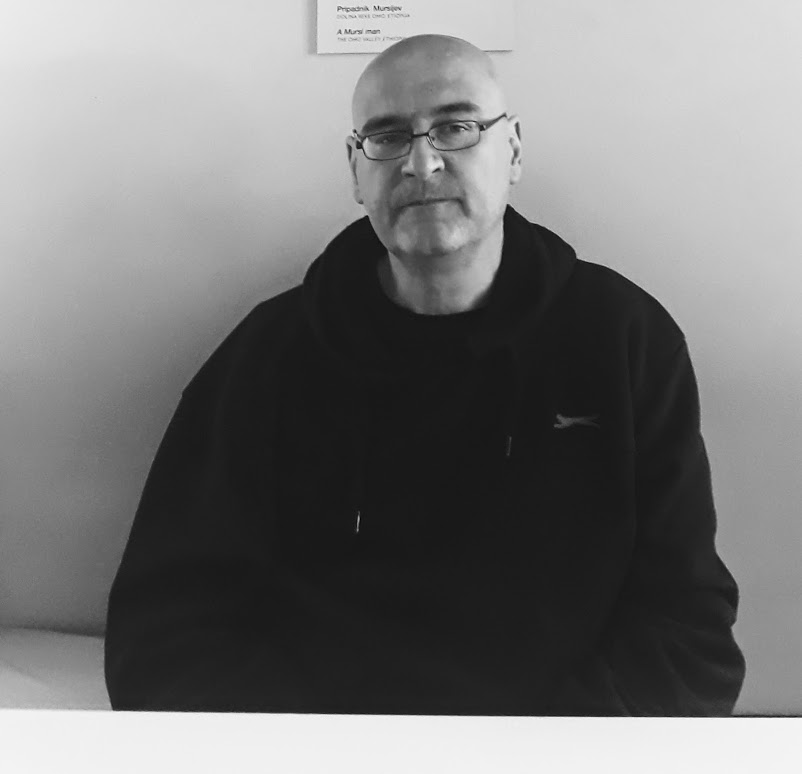

Andrej Lokar is a Slovenian conservative essayist, translator, philosopher, journalist, and president of the Kdo Art and Culture Association, born in Trieste. He is the organizer of numerous cultural and artistic events and the author of the 2015 book Vračanje mesečine (The Moonlight Returns). Since 2017 he has been President of the Cultural and Artistic Association KDO? (Who?). He has published numerous essays and articles in magazines such as Dnevnik, Delo, Večer, Slovenski čas, Mladika, Zvon, Kud online philosophical portal and in the online magazine Hungarian Conservative.

***

How do you view the actions and policies of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán?

I cannot say anything about the internal political activities of Viktor Orbán because I do not live in Hungary. But there is a move that is very attractive to Slovenians—and that is the victory over, or at least the restriction of, the deep state. We can see the results, but I don’t know how this victory was achieved. I think Orbán is one of the first conservative politicians to understand the inevitability of the culture war. We are already in a culture war; it is not a matter of whether we want it or not. The goal of winning the culture war, however, is not to defeat the opponent but to build and establish a new ‘hegemony’, or—if we talk as conservatives: the revival of the inner essence of the elements is already present in the collective unconscious at the level of Burke’s ‘prejudice’. The New Right needs a cultural apparatus, record labels, producers, media, exhibition spaces, and educational institutions to do this.

Why do you think so?

Because it is necessary to change people’s feelings. Viktor Orbán understood that even if you win the elections, you cannot govern if all the elites in society oppose you. Therefore, you must act as a charismatic catalyst for the elites who espouse conservative views and allow them to create an atmosphere in society that is conducive to conservatism. This phenomenon is called the social legitimation of politics and is one of the key concepts of conservative political philosophy. If we look around the world, the situation is currently very favourable to conservatism. The narrative of left-wing progressivism is increasingly anachronistic; the left has made a pact with neoliberal capital, but it has left the weakest strata of the population to their fate; after the wave of neo-Marxism, it has not been able to formulate a political philosophy that would cope with the situation in modern society. Its impotence is manifested in the fact that it knows only one approach: anti-fascism and the awakening of the fear of fascism. Anti-fascism is legitimate as a historical stance—it is opposed to fascism. As a universal worldview, however, it is utter idiocy since it assumes that there is some view in political history that has introduced some absolute evil into it while history as such has been absolutely good. And that rebellion against this evil will restore its absolute goodness to history. Conservatives know that evil is as inherent in history and politics as it is inherent in all things, and it is a matter of ethics of individuals and groups whether we choose good or evil. However, being aware of these historical moments is Viktor Orbán’s greatest virtue.

‘Conservatives know that evil is inherent in politics, and it’s a matter of ethics of individuals and groups to choose good or evil’

What are the chances of the Slovenian right to win the elections?

The chances of the Slovenian right (or rather, the Slovenian centre-right) winning the elections depend on many aspects. In my opinion, the following is particularly important in this regard: the situation in Slovenia is such that a simple victory is not enough; Slovenia needs a centre-right win that would allow for a stable government to govern for two mandates and to carry out reforms that are necessary for Slovenia’s survival as a sovereign state. Given the fragmentation of the Slovenian electorate, this presupposes two things: a) a strong pre-election party coalition led by the currently strongest centre-right party; b) a strong civil society coalition of various social subjects which would enable the pluralism of such a coalition and, above all, legitimize reforms which in some cases must be very draconian. The soft totalitarianism of the mutated left has gone so far in Slovenia that it threatens the existence not only of the Slovenian state but also of the Slovenian nation. Slovenia needs a radical alternative to the ‘ruling from behind’ that is characteristic of the veterocommunist continuity of the deep state. Of course, this can only be done by the centre-right, but it must clearly position itself as a radical alternative, just as it happened at the time of Slovenia’s independence. However, even the approaches of Slovenian autonomy are no longer appropriate because, in our case today, we are dealing with two problems: a) the hybrid survival of the totalitarian system that has infiltrated all pores of our social life; b) an incomparably more uncertain time than that of the end of the Cold War. Any decision will lead us into the still unformed world of new ways of political life and new ways of international integration, which will require us to invest all our creativity. For all these reasons, the centre-right must formulate a clear programme for Slovenia, and the civil society that supports it must closely monitor the implementation of the programme. We need a broad grassroots movement to completely transform our country and instil hope in all citizens.

What about conservatism in political parties in Slovenia?

In Slovenia, due to the already mentioned lack of reflection regarding conservatism, we do not have any conservative party in the true sense of the word. At the time of Slovenia’s independence and also immediately after it, there was a party called the Peasants’ Union (Kmečka zveza), which most closely resembled a conservative party but then merged with the Christian Democrats. That is why it is better to speak of ‘centre-right’ than conservatism in relation to Slovenia. The Slovenian centre-right has three parties: the strongest Slovenian party ever, the SDS, and two Christian Democratic parties, NSi and SLS; the first is parliamentary, and the second has not crossed the parliamentary threshold for a long time. With centre-right governments, these parties try to form coalitions with other parties that do not directly belong to the centre-right, and therefore, these coalitions tend to be fragile and unstable.

What about the SDS?

The SDS party has the most conservative elements, but its views on democracy, society, the economy, politics, and people are not conservative. Instead, they belong more to the realm of classical liberalism, which is naturally adapted to the Slovenian situation. The party has a charismatic leader, Janez Janša, and its strongest point is a stable electoral base rooted in the Slovenian countryside, which, of course, as I have already mentioned, is the most conservative in Slovenia. Essentially, it could be defined as a classic liberal party but one that has a conservative electoral base. Its greatest merit is the fight against the survival of regime communism in our society and the effort to dismantle the deep state. That is its greatest virtue, and that is why I always support its rule. Both Slovenian Christian Democratic parties have eventually alienated themselves from their traditional voters, who make up about 20 per cent of the total electorate. They are currently pursuing an inconsistent policy and are not able to mobilize the entire Christian population in a uniform manner. The consequence, of course, is that explicitly Christian content, such as subsidiarity, is disappearing from Slovenian politics.

Does Central European conservatism even exist?

Regarding conservatism, it is always difficult to determine in advance whether some regionally conditioned form of this school of thought exists. In my opinion, in this case, we should first define two things as precisely as possible: a) what Central Europe is and b) what is the corpus of conservative thought on the basis of which we could measure the Central European conservative experience. It seems most appropriate to me to take the work of Roger Scruton as a fundamental measure of conservatism since Scruton’s philosophy is similar to Hegel’s in this respect: he created a philosophical space that we must cultivate and develop in accordance with our beliefs and needs and of course in harmony with the philosopher’s guidelines. That is to say, the reading of Roger Scruton must be done methodologically, taking into account the basic guidelines of Central Europeanism that we have mentioned. The final step, however, is the rediscovery of Central European thinkers who considered themselves conservatives, as well as conservative elements in those who did not consider themselves conservatives. So, I would formulate the answer to your question as follows: the existence of contemporary Central European conservatism has yet to be methodologically discovered through a comparative study and the harmonization of three aspects: a) the defined common Central European space/tradition; b) the modern conservative canon and the conservatives who preceded the chosen canon; c) the ideas of Central European conservative thinkers and conservative ideas and phenomena in society itself. As Edmund Burke would say, Central European conservatism exists at the level of ‘prejudice’, but it has yet to be articulated.

‘The nation-state is the foundation of today’s international political order’

What about Central European conservatism in contemporary politics?

On the contemporary political scene, the idea of Central European conservatism as the only force that can reawaken Central European identity seems to be becoming more and more topical. Only conservatism can revive elements of a tradition through a selective approach, and the revival of a common Central European tradition could represent a political counterweight to the hegemonic aspirations of Western European member states or founding member states of the European Union on the one hand, and a counterweight to the political ambitions of Russia and its allies on the other. Although this topic is no longer so topical today, Central Europe is not only a mediatior between West and East but also a mediatior between North and South. The characteristic of Central Europe is that it possesses elements of all the above-mentioned geopolitical dimensions: West, East, North and South. At the same time, of course, it does not fully identify with any of them. Of course, all of this means, above all, returning Europe to its identity. The EU project has uncritically taken up a liberal and progressive agenda, which unfortunately has also prevailed among Christian Democrats, and has thus turned away from a fundamental feature of the European continent: the so-called Europe of nations. All this, of course, also presupposes a new geopolitical redistribution of the world.

Do you feel that Central European states are alien to each other?

All states must be alien to each other to some extent; otherwise, they would not constitute themselves as independent and sovereign states. And if they weren’t alien to each other, they wouldn’t need to be connected. Therefore, it is necessary to define what alienates them and, above all, why they need to be connected. What historically, in the past, united Central European countries was that most of them were not states at all. Central Europe has been connected since the Middle Ages, and it has been torn apart by the inability of its elites to create a centripetal force that would allow individual entities to maintain their sovereignty (which was just awakening in them at that time of crisis) while remaining in some loose connection. Central Europe is a paradigmatic example of why the idea of a Europe of nations always remains unrealized: there is a nation that is experiencing the peak of its heyday in any historical period and wants to subjugate all others based on territorial claims, which are the biggest problem in Central Europe as national borders between individual nations are not precisely drawn. All this, of course, is a great challenge for the nation-state, which is the foundation of today’s international political order.

In the case of multinational configurations, the dominant political entities respond with centralization (which is also the case now in the EU). Looking at this issue from a historical point of view, then, we can see this: for the first time in their history, Central European peoples and nations feel the need to unite as recognized nation-states, which presupposes that they must determine from the outset exactly how they will guarantee the rights of indigenous nationalities (minorities) living outside their nation-states in the event of an alliance. This would avoid the most dangerous hotbed of conflict. At the same time, however, some kind of political link should be established, which would take place first at the economic level because this is the area in which it is easier to reach a consensus. This would create at least the first outline of a common belonging and, above all, a common goal. The most important thing about these types of projects is that they contain some prospects for the future in their design.

‘Central Europe did not know the revolutionary Enlightenment because it manifested itself through reforms by political elites’

Do you think that the cultural elites and politicians of Western Europe understand what Central Europe is?

If we consider the political and cultural structure of the new and even the newest generation of politicians and members of various commissions in Brussels, it goes without saying that they cannot understand Central Europe. Everything, including politics, in Central Europe, as Scruton and Hazony would say, has its origin in something that is expressed through a commitment to a tradition that acts not only individually but collectively and in a prerational way. That is to say; the fundamental Enlightenment-liberal pattern does not apply in Central Europe: that there is a universal reason, that the use of this reason is available to every human being, and that this inevitably leads us to universally valid truths that are the property of humanity as a whole. The application of this reason, if we just so desire, leads us to the inevitable realization that there is a political order based on reason and which is the optimal solution for man as such, regardless of the circumstances. And this order is called liberal democracy. It is enough to introduce this order by some decree anywhere in the world, and the very reason the individuals we will include in it will tell them that it is the perfect order that can be achieved for all mankind, anywhere and at any time. It is, therefore, an arrangement that transcends space and time. This understanding of man and the world has become common sense and extends to other areas: law, economics, and science. It goes without saying that such an approach cannot be accepted in Central Europe because of its particularity and for the sake of individual identities, which, also due to the lack of state frameworks, are rooted primarily in traditions. The only thing it can do is impose on these subjects some a priori solutions that have been born in brains prone to abstractions. And that’s exactly what’s happening in these days.

What about the great conservative thinkers? Do we have any Burke or de Maistre in Central Europe?

In Central Europe, of course, we have our conservative thinkers, but we do not have such cardinal or seminal theorists (and, ultimately, practitioners) as Burke and de Maistre. Of course, we have to ask ourselves why this is so. If I try to understand this from the Slovenian point of view, I have to say that Slovenians did not have a layman and creative reaction to the Enlightenment. This is also a consequence of the fact that the Enlightenment in the Habsburg Monarchy was, of course, not the French Enlightenment. We can cite the reforms of Joseph II, but this is certainly not comparable to the movement of the philosophes of the Encyclopedia. Conservatism was indeed decisive in politicians such as Klemens von Metternich and also Alexander Bach, but in both cases, they were not theorists. Of course, there are thinkers like Adam Müller and Othmar Spann; there was Karl Mannheim from Budapest; Leo Strauss was an important thinker; artists like Hugo von Hofmannsthal were also conservatives, and conservative tendencies are present in Stefan Zweig and Joseph Roth. Important to conservative thought was Richard Thurnwald. The Hungarians have John Lukacs, the Poles have Ryszard Legutko. Roger Scruton also counts Hayek among the conservative thinkers, which I do not think is true because he himself explicitly said that he was not a conservative and, above all, it is quite clear from his essay about conservatism that he did not understand what conservatism even was. However, I think Central Europe did not know the revolutionary Enlightenment because it manifested itself in our environment through reforms introduced by political elites. This presents an even greater challenge for us to find these roots and build a new paradigm on them.

What about Slovenian conservatism?

The situation with Slovenian conservatism is as follows: if we look at it historically, at the time of the birth of Western conservatism and also at the time of its predecessors, we did not have conservative thinkers: moreover, our conscious culture (especially literature) which was literally the creator of our modern (including political) identity was led by liberal cultural elites, as much as by intellectuals on the periphery of European events who were as libertarian as possible at that time. We can even call them classical liberals. Liberal elements prevailed in our culture, even during the Romantic period. In essence, however, it is more a matter of the so-called Freigeist, which was popular in German-speaking countries. Of course, there is a Slovenian identity that is pre-modern, that was monopolized by the Roman Catholic Church, and that knows a rich liturgical but certainly lower quality creativity. That is to say, Slovenians have never had secular conservatism but always a form of conservatism that was expressed predominantly by the clergy and was primarily reactionary. The Slovenian nation has deeply conservative tendencies in its understanding of the world, but its conservatism has never been reflected.

Another problem is of a sociological nature: due to the loss of our indigenous ancestral nobility in the Middle Ages and due to the limited development of the bourgeoisie (we did not have large urban centres), we did not stratify (or stratified dysfunctionally), and the consequence was that our progressive intellectual elites, who literally built our self-informed image, accepted the progressive mindset as the only one which should correspond to our condition and, above all, to our development. This does not mean, however, that the part of our collective self that has remained unreflected and inarticulate has disappeared; quite the contrary: it still fatally determines our essence, which, precisely because of this, is somehow divided.

‘The Slovenian nation has deeply conservative tendencies in its understanding of the world, but its conservatism has never been reflected’

What is the task of Slovenian conservatism?

The task of Slovenian conservatism, therefore, is to articulate this inarticulate lack of reflectiveness and, based on a selective study and application of general conservative doctrines, to make concrete an identity that already exists on a potential level. The most interesting thing is this: our ideological opponents, who are trying to deconstruct our tradition, keep saying that it is necessary to prevent the ‘retraditionalization of Slovenian culture’. Selective retraditionalization, however, is exactly what we do with our publishing house and our online reviews.

What books do you publish?

The fate of our publishing house, the Kulturno umetniško društvo KUD KDO, is paradigmatic for today’s situation in Slovenia. Our publishing house has seven collections that differ in colour on book covers: the blue collection for conservative thought, the yellow collection for fiction, the pink collection for general philosophy, the purple collection for the essayists, the burgundy collection for music, the green collection for topicality and the okra collection for religious studies. The key, of course, is the blue collection for conservative thought, which revolves around the works of seven cardinal authors, which we attempt to translate in their entirety: Ernst Jünger, Roger Scruton, Robert Nisbet, Michael Oakeshott, José Ortega y Gasset, Ramiro de Maeztu and Nicolás Gómez Dávila. At the same time, we publish two online magazines, one for arts and culture, Kdo?, and one for political thought, Anamnesis. We intend to publish translations of all the classics and modern authors of conservative thought, as well as contemporary critics of cancel culture, wokeness, cultural studies, deconstruction, etc. In other words, our intention is to win the culture war. Of course, this has met with unspeakable resistance and the cultural establishment, which is supported by the deep state in Slovenia, is trying in every way to destroy us.

Is it possible to import the English version of conservatism?

The English or Anglo–American version of conservatism cannot be imported into Central Europe for a number of reasons. Both British and American conservatism are forms of this political philosophy that are deeply rooted in the traditions from which they are derived. The fundamental principle of conservatism is most recognizable precisely in the British and American juridical and sociopolitical experience: that the formalization of law already exists ante litteram, in the commitment that creates the cohesion of a community even before it is expressed in legislative form. Essentially, it is an understanding of sociogenesis that is radically different from the liberal and socialist one because it is based on a completely different understanding of man as an individual. All of this, in some respect, is the result of the development of these nations in the process of historical becoming. This is unique and unrepeatable. Therefore, the approach I advocate is this: non-English and non-American conservatives must first examine this organic development, then view their particular historical development selectively choosing conservative elements in it and, on their basis, formulate a form of conservatism that is consistent with their specificity.

What is the situation at Slovenian universities?

The situation at Slovenian universities is similar to that at universities throughout the Western world. The elites formed by Slovenian universities are used by left-wing parties to ‘cleanse’ Slovenia of elements that they consider reactionary or dangerous to their total power. The strategy is as follows: when these parties are in control, they fill all institutions and NGOs with their people, set up new NGOs and give them powers that they should not have, such as being able to even propose laws. The consequence of this state of affairs is, of course, that in the case of a defeat in the elections, these cadres completely control culture and the media, especially the subsidy mechanisms. This creates a mechanism of control in Slovenian society led by the misuse of public funds, which no one controls or can control. All of this is maintained by taxpayers without insight into what institutions are doing with their money. This causes terrible social dysfunction. Individuals who are appointed to various commissions to utterly massacre everyone who is not left-wing are mainly employed at the universities as well. All I’ve mentioned does not only mean negative selection but also an obstacle to privatization and establishing normal economic or property relations. Slovenia has become a completely lawless state; courts judge on the basis of political affiliation, the police treat citizens based on political beliefs, and the powers that dominate the country from behind prosper on the basis of economic crime.

Related articles: