The reigns of Angevin Kings Charles I (r. 1308–1342) and Louis I (r. 1342–1382), coming from Naples, are traditionally regarded as the first outstanding period of Hungarian chivalric culture. The secular elite in Hungary was moved by the same ideals of pruesse, largesse, loyauté, courtoisie, and foi de Dieu as their counterparts in Europe, and had ample opportunity to practice them. Wars were a natural part of these decades, and from the 1330s onwards, campaigns were launched in all directions almost yearly. During the reign of Charles, we know of some 42 major military ventures, while the reign of Louis, later known as the Great, saw 35, 16 of which were personally undertaken by the Monarch himself. Louis’ campaigns to seize the throne of Naples (1347, 1350) forced his court and troops to make a world tour. King Louis himself was named after the holy bishop of Toulouse, the idol of the Angevins, but the same name was also borne by King Louis IX, whose chivalric virtues he emulated in many respects. It was of no coincidence that the unrivalled personality of the Monarch attracted many well-known knights to his court, such as Burkhard von Ellerbach and Ulrich von Cilli, who played a major role in spreading chivalric ideals and customs at home.

We have learnt about the details of the campaigns mainly from the royal charters, which were the only way for those who made sacrifices in battle and then won charters to record their heroic stories in writing, thus supporting not only their own future and career but also that of their families. As only they could provide precise information on the details of the physical and material damage and injuries suffered in battle, they were actively involved in their writing. These charters were also the most important channels for the dissemination of chivalric ideals and the ideals of courtly service and made it clear to the society concerned that chivalric service, heroism, and sacrifice ennobled those who deserved it, and brought with them royal estates, material, and social recompense. The opinion of Hungarian researchers that certain elements of the lost Hungarian chivalric literature can be reconstructed from these very documents is not without foundation. The values propagated in the chivalric period did not change: loyalty, courage, honour, and the desire for fame. As was clearly stated in the introduction to the biography of King Louis the Great: ‘For he who truly desires fame will be famous and glorious. Glory is the supreme and self-evident requisite of reign, for we do not seek to reign for its own sake, but for the glory that comes with it. The beginning of wisdom and understanding, then, is the desire for fame.’[1] The secular elite could prove their loyalty daily, and we see them as the valiant nobles of the ‘bons barons de France’ in the pages of the Chanson d’Antioche.

The Hungarian chivalric culture is a very controversial phenomenon, as knighthood in the Western sense of the word did not develop as a social stratum and group. All this is further complicated by the fact that there are hardly any written sources on the cultural background of knighthood, except for charters and biographies of King Louis. Nevertheless, much was transmitted from the royal court to the elite of Hungarian society at the time, and from them to the wider circles of warriors.

‘The Hungarian chivalric culture is a very controversial phenomenon, as knighthood in the Western sense of the word did not develop as a social stratum and group’

In Western courts, the most reliable traces of the period were preserved not just in Latin but also in vernacular literature—here, however, there is hardly any surviving Hungarian-language secular literature. The only possibility seems to be the search for first names that can be associated with the literature of the knights and the court. Thus, the first names of characters in the stories of Troy, Alexander the Great, and the Songs of Roland have appeared in the process of giving names. Interestingly enough, the names in these stories (Roland, Olivier, Olivant, Achilles, Priamos, Hector, Helen, Tristan) already appear in the sources from the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, first among the nobility and later among the commoners and the townspeople who had moved from the West.

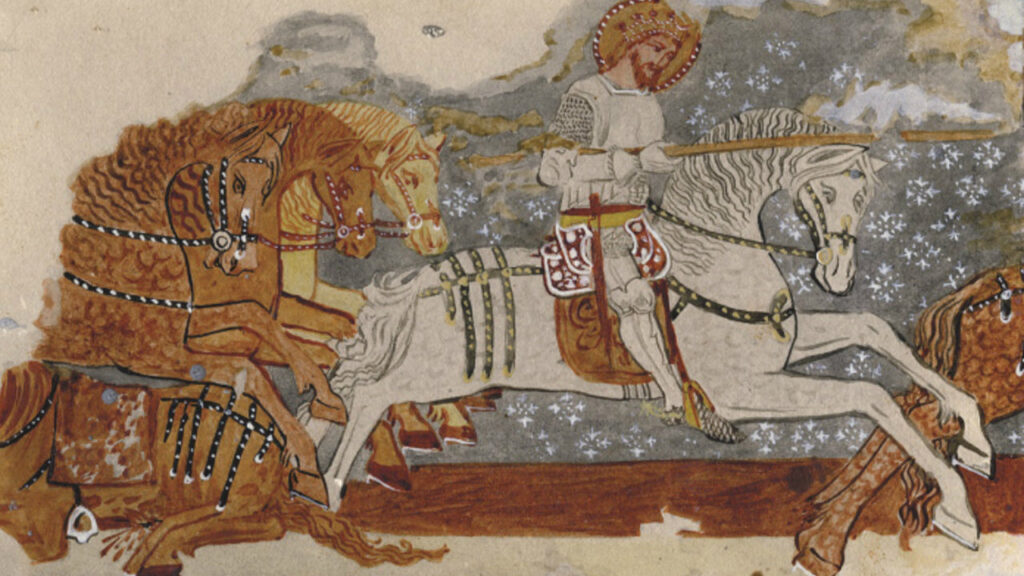

The most notable of our artefacts is the belt buckle of Kígyóspuszta, found in 1816 in the Great Hungarian Plain, with four buttons depicting warrior saints. On the buckle is a picture of a tournament between two teams of horsemen, the knights wearing a chain mail, the musicians holding a horn and a cymbal.[2] The interesting thing about the find is that the buckle was found in the tomb of a prominent Cuman, which explains why the nomadic Cumans maintained their pagan burial customs long after their settlement in Hungary in the mid-13th century. Thus, the graves of the Cuman ruling class give us an idea of the material culture of the royal and aristocratic centres of the period. These objects were most likely given to their owners as royal gifts, as was the Western-type double-edged sword from Kunszentmárton, which was decorated with the Dynasty’s coat of arms.

The typical Hungarian knight-saint became Saint Ladislaus, whose propagation by the new dynasty of Neapolitan origin can be seen as a sign of alignment with Hungarian traditions.[3] Art historian Zsombor Jékely strongly argues that the St Ladislaus fresco cycles, of which nearly half a hundred are known today, appeared in the Kingdom of Hungary during the Angevin period, at the earliest around 1310–1320. Their appearance was a pictorial expression of the Dynasty’s perception of legitimacy. It is believed that the paintings reflect the Neapolitan transmission of 13th-century French crusader art.[4]

Surprisingly, the earliest secular order of knights founded by royalty was in Hungary, just after the civil war.[5] We have a charter and seal of the order dating back to 1326, and we know that the order was organized near the chapel of St George at the royal seat of Visegrád. Probably it was the almost fatal assassination attempt on the royal couple in Visegrád in 1330 that put an end to the King’s efforts to establish the order, even though the main motive for its foundation was precisely to speed up the process of the local nobility’s attachment to the new dynasty.

‘It was an unprecedented period in Hungarian chivalric culture when Charles restored the authority of royal power and Louis reaped the benefits of his father’s policies’

However, only a few were privileged to represent the king as ambassadors at foreign courts, and of course, few were qualified to do so. In 1359 Benedek Himfi, then only a knight of the court, and András Lackfi, Voivode of Transylvania, had the privilege to travel to the papal court in Avignon as the king’s envoys. Like thousands of other Hungarians, Miklós Toldi spent long years on the battlefields of Italy in the mercenary service of the city-states.[6] A chosen few had the opportunity to encounter the high culture of Europe at the time, while the knights of the court fighting on the battlefield must have gained a much more superficial impression. The time of captivity offered a special opportunity for this, as Voivode István Lackfi could experience it in Venice. He was taken prisoner in 1373, and we know that he was given a room and distinguished guards in a Venetian palazzo, perhaps the Palazzo Ducale itself, the Doge’s Palace. Court people also had the great advantage of being able to marry within the aristocracy, using their court connections, sometimes to foreign princesses, and to have their children educated abroad.

The Hungarian court had embraced the crusading idea since the 13th century, which was transformed into campaigns against the Orthodox Christians and ‘heretics’ of the Balkans from the middle of the century. The Baltic region was also a favourite target for European crusades against the pagan Lithuanians and Prussians. We know of two Lithuanian campaigns led by King Louis, but we have no knowledge of any Hungarian nobles taking part in the Preussenfahrt (Prussian Crusade) without the King. At the same time, pilgrimages to the Holy Land were popular among the nobility of the time, and permission was often obtained before they became barons. Benedek Himfi, castellan and county steward, later a Bulgarian ban, asked permission to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land with six of his party in 1357, which he did in 1376, while István Lackfi chartered a boat from Venice for himself and 14 companions in 1376.

It was an unprecedented period in Hungarian chivalric culture when Charles restored the authority of royal power, and Louis reaped the benefits of his father’s policies. At this time the court of the Hungarian kings had international clout and a network of contacts indeed, with King Louis corresponding with influential figures such as poet Petrarch and famous Florentine chancellor Coluccio Salutati. ‘The Hungarian chivalric culture had an important historical function in the development of Hungarian civilization, to bring for the first time a secular colour and character to Hungarian cultivation after the decay of the ancient pagan culture.’[7]

[1] Johannes de Thurocz, Chronica Hungarorum, Erzsébet Galántai and Gyula Kristó (eds.),Vol. 1, Textus, Budapest, 1985, p. 160.

[2] David C. Nicolle, Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050–1350, White Plains, New York, 1998, Vol. 1, p. 544, and Vol. 2, p. 940 (nr. 1513).

[3] Ernő Marosi, ‘Between East and West. Medieval Representations of Saint Ladislas, King of Hungary’, The Hungarian Quarterly, Vol. 36, 1995, pp. 102–110.

[4] Jékely Zsombor, ‘Narrative Structure of the Painted Cycle of a Hungarian Holy Ruler: The Legend of Saint Ladislas’, Hortus Artium Medievalium – Journal of the International Research Centre for Late Antiquity and Middle Ages, Vol. 21, 2015, pp. 62–74.

[5] László Veszprémy, ‘L’ordine di San Giorgio’, in Enikő Csukovits (ed.), L’Ungheria angioina, Roma, 2013, pp. 265–282.

[6] Attila Bárány, ‘The Communion of English and Hungarian Mercenaries in Italy’, in János Barta and Klára Papp (eds.), The First Millennium of Hungary in Europe, Debrecen, 2002, pp. 126–141.

[7] Klaniczay Tibor, ‘Lovagi kultúra’, in István Sőtér and Pál Pándi (eds.), A magyar irodalom története, Vol. 1, Budapest, 1964, p. 72.

Related articles: