I first met Jeff Kaplan shortly after arriving in Budapest, in the baking heat of early July, 2021.

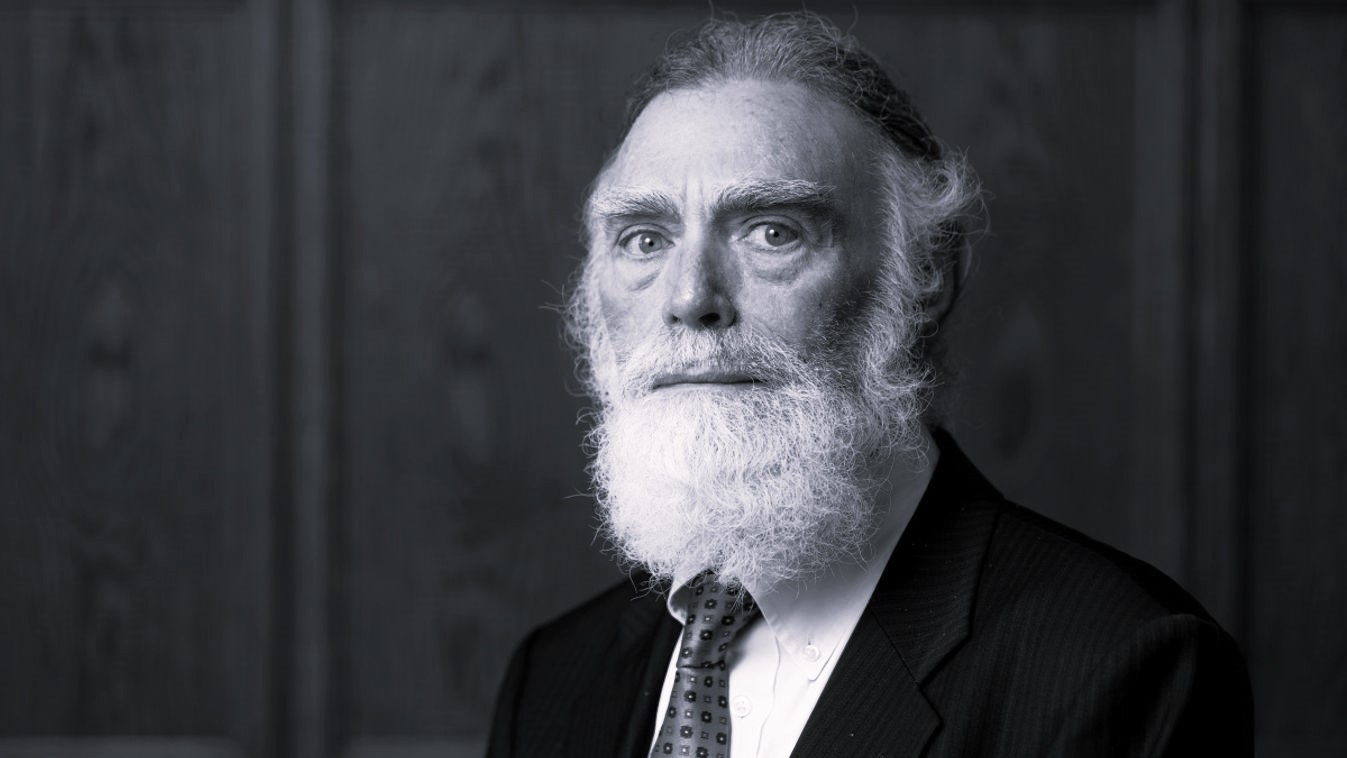

Browsing my new institute’s website, among the profiles of my colleagues one stood out: a man with an untamed beard, tight ponytail, and piercing stare. Intrigued, I googled his work.

Discovering a common interest in millenarian movements, I shot off an email, attaching a half-drafted piece on the topic, not expecting it to be read.

Within hours, I had a response. He’d not only read the draft, but done so attentively. His email wove together encouragement with gentle corrections. It riffed widely on our shared theme, before landing on a compelling conclusion:

‘We should have lunch.’

We arranged to meet the next day, near the institute, in the dappled shade of Liszt Ferenc Tér.

Although he was, I’d discover, an intensely private man, Jeff could never pass unnoticed in any street. Rangy, with a sinewy athleticism even in his mid-sixties, his movements were nevertheless always cautious and unhurried.

He was therefore easy to spot, pulling on his pipe, Australian bush hat in place. A man of living paradoxes, in motion he invariably appeared lost in thought while also intensely vigilant to his surroundings.

To spend time with Jeff was to converse with someone governed by private rituals and routines, like a man used to silence, isolation, and the rhythms of the real world that most of us have lost a sense for, in the din of digital distraction. Belying the obvious intensity of his inner life, he created around him a refreshing sense of calm, and of time slowed. Faced with a problem to solve, he would invariably begin packing and tamping his pipe.

Like a great athlete, Jeff had the rarest of skills: an ability not to react to a pace set by others, but to set the pace to which everyone else must react. In conversation, this was especially evident. It was the hallmark of a great teacher, or mentor. In another life, where he did not dedicate himself to the study of radical movements, he had the presence of one who might have started one.

But Jeff was not all mystery and quiet, uncanny charisma. Discovering we had both spent years playing the most solitary position in organized sports—goaltending in ice hockey—we would occasionally meet at his apartment to watch pre-recorded NHL games. His knowledge of the league and its statistics was encyclopaedic. Not given to talking about himself, I never learnt where exactly Jeff grew up. Yet, watching him lean forward in his armchair in Budapest, a beer in one hand, and a slice of pizza in the other, cursing at the TV as his team gave up the puck in the neutral zone, one could imagine a winter wind whipping through a small town from the Great Lakes.

Jeff and I shared one big adventure: in 2023 he invited me to join a two week field-work trip to Iraq. There, at work, his paradoxes made sense. How else, in fact, could one spend a lifetime conducting fieldwork in forsaken places, without an ability to be at once lost in thought while also remaining hyper-vigilant?

Professor Jeff Kaplan had the aura of a man burdened by secrets, but untroubled by convention. What the former were, and how he achieved the latter, were questions his very presence provoked from our first meeting under the bower of the Plane trees that lunchtime. These questions were never answered, but never lost their mystique. He was a singularly memorable figure, as indelible in presence as he was enigmatic in nature.

Along the way, he wrote good and important books, and saw and cultivated the potential in others. He will be missed by many, not least here in Budapest, where he made his home the last five years of his life.