President Trump’s recent shift in terms of US foreign policy regarding relations with continental European states as well as his initiations of negotiations with Russia have caused uproar and negative reactions. Elements of the foreign policy establishment which has dominated for decades are quick to employ the absurd ‘ad-Hitlerum’ tactic. A general rule of thumb seems to be that any approach that does not include foreign policy adventures thousands of miles away from American soil or prioritizes the welfare of domestic citizens is to be considered as ‘Isolationism’, ‘Appeasement’, and paving the way for the next ‘Hitler’.

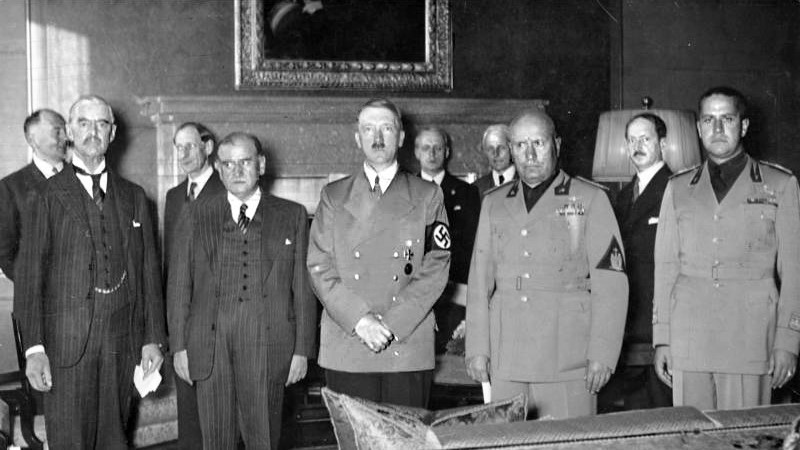

The Munich Angreement and crisis is considered as a canon event in world history. Probably it’s the only diplomatic episode most people have ever heard about. It is unlikely to hear of any other historical analogies to our contemporary events, even though there are others that seem to fit better.[1] As we know, ideology oftentimes blurs the lines between objective reality and ideals. European elites are more than happy to join in this quest of total denial of on-the-ground reality in Ukraine, and the general realignment of the geopolitical field since 2022.

Nevertheless, one thing that remains unchanged is the prevalence of inaccurate 1938 Munich analogies trying to steer the discussion away from honest debate. Indeed, any politician who has tried to mediate thus far between the sides is to be linked to Neville Chamberlain. As the dominant narrative says, he was weak and failed to prevent German expansion. On the other hand, politicians who advocate escalation are the Churchills of our time, willing to fight evil. Few phrases other than ‘Appeasement’ might have a more detrimental effect on a person in the world of International Relations.

‘One thing that remains unchanged is the prevalence of inaccurate 1938 Munich analogies trying to steer the discussion away from honest debate’

For better or worse, history is not so simple. However, reducing it to a black-and-white interpretation, it leads to a woeful misunderstanding of the nature of WW2, the general Grand Strategy, but also of the situation that the West faces in Ukraine at this very moment.

To begin with, Chamberlain was definitely not this uninspiring, feeble, delusional person that most people have come to believe. Nor were his decisions before 1 September 1939 irrational or catastrophic. Winston Churchill, who on the other hand is usually portrayed as the antithesis of Chamberlain, was far from perfect. His famous debacle in Gallipoli in WW1 is often cited, but not his other equally disastrous decisions: including Norway, the sinking of the Prince of Wales & Repulse, the fall of Singapore, the Greek & North African campaign during WW2, or the humiliating concessions Britain had to make to the USA.

Churchill is also suspect of an even greater act of ‘appeasement’ regarding the post-war settlement of Poland, for whom Britain entered the war, but then let is become a socialist republic within the Soviet sphere.

To circle back to 1938 Munich, it is true that both France and Britain hoped to avoid a European war through concessions to Germany and Italy—then still wary of German ambitions before Anschluss. Both France and Britain had not healed from the wounds of the Great War, and neither had their respective population. A declaration of war against Germany, which was revamping the map of its neighbourhood after the territorial losses of Versailles, would have amounted to a political suicide. We also cannot forget the fact that another regime in Moscow presented itself with an equal threat to the West. The last thing that the British and French would want to do is exhaust themselves in another war of attrition against Germany, thereby tipping the balance of power in favour of Moscow. Even worse, as seen later by the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact, push these powers together in a temporary struggle against the Capitalist West.

Taking aside the poor general understanding of the pre-war period, it is also a blunt myth that Chamberlain was under the illusion that war could certainly be avoided if he appeased the German side: ‘It is perfectly evident surely now that force is the only argument Germany understands, and that collective security cannot offer any prospect of preventing such events until it can show a viable force of overwhelming strength backed by determination to use it’.[2]

The typical appeasement narrative ignores the nuances of Grand Strategy and historical context. By 1937 Britain had found itself in a difficult situation concerning its strategic position. It was underprepared for war; it lacked in armaments and especially airpower, which was vital. The RAF consisted of mostly biplanes, with no Spitfires in production lines as of yet. Britain needed to avoid at all costs conflict on potentially three fronts: against Germany in mainland Europe; Italy, which was threatening British power in the Mediterranean; and Japan, which was also a threat to British overseas possessions in East Asia. In this scenario, it was all but clear that the Royal Navy would have been overstretched, and in that case a fatal blow against the British Empire could have been struck. Thus, any sensible policy would have to follow compromises to at least one of the sides to avoid this catastrophic scenario.

Both Britain and France needed time to mobilize, increase output, and gather resources. Germany at the time was going through an unprecedented but unsustainable military build-up, with the hope that territorial gains would be able to pay it off. Nevertheless, by all economic measures the Allies seemed to have time on their side, and in the long term their economic potential, resource abundance, and potential Naval blockade, just like in WW1, would have strangled Germany through a long sluggish war of attrition. Engaging prematurely before 1941 or 1940 would have meant that Germany would have had the upper hand in the short term.

As for the 1938 crisis in Czechoslovakia, it is true that the Czechoslovak armed forces had considerable defensive capabilities along the Sudetenland, but these could be bypassed after Germany’s Anschluss with Austria. Aside from this, the Allies did not fare much better either in terms of airpower.[3] As the events of 1939 proved, a year later an offensive on the Western border of Germany would have been unlikely. In other words, it becomes evident that even with a declaration of war Czechoslovakia would have done all the fighting in the opening stages.

‘Appeasement, as understood by strategy theory, is a perfectly rational choice as long as it is a short-term policy’

For all the talk of Chamberlain as naïve in his predicament, it was Hitler who believed in the aftermath of the Sudeten crisis that he had been outmanoeuvred, since he did not get his early war. Nor could he count on the growing German economic power, which was losing steam. Britain did not scale back on its rearmament programmes but instead significantly accelerated them. Its output grew, and increased total divisions could be placed in mainland Europe. Following the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, both Britain and France could count on the enormous American industrial capacity to bolster their armaments efforts. Ultimately, the beneficiaries of Munich were Britain and Italy rather than Germany.

The situation by 1939 seemed more detrimental to the German side than to the Anglo–French alliance. As for Germany, her dwindling resources were causing major issues,[4] and an oil crisis would have been imminent if not for a new trade deal with Romania. The German General Staff was expecting to be able to conduct full operations against the West for no more than a year at most. Considering production figures at the time, Britain was already matching German aircraft production, and, ceteris paribus, the balance of power would turn decisively by 1941.

It might be the case that the decision not to declare war in 1938 can be considered prudent. Indeed, as controversial as it might sound to some, appeasement, as understood by strategy theory, is a perfectly rational choice as long as it is a short-term policy with a strict schedule to turn the balance of power against the aggressor, through either internal or external counterbalances.

The unexpected signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact gave Germany a new lifeline to sustain its operational war capabilities for a longer time period, but this was not indefinite. Germany still faced huge issues in relation to resource deficits. The 1939 invasion of Poland was the last chance for Hitler to play his huge gamble of a short-term war, in hopes of achieving a decisive victory in a matter of a year, at the absolute most.

What we know for sure is that Hitler was very lucky in relation to the Ardennes thrust. Had it not been for the Mecklen incident is it probable that a similar repeat of the Schlieffen plan would have led Germany to a disastrous war of attrition, which it was doomed to lose.

The final assessment in terms of the policy of appeasement would be that at the diplomatic and political level, the allies did indeed achieve their goals of buying time, mobilizing, as well as isolating Germany in the first months of the war from either Japan or Italy.[5] They made Germany dependent on Soviet resources to sustain short-term operations, and pushed its economy on the brink of collapse. The embarrassing failures in May and June of 1940 at the operational and tactical level by the Allied military command overshadow all the following factors that prove that the British and the French were under no illusions that a piece of paper would be able to guarantee peace.

One could argue again that the right course of action could have been different in 1938. There were factors at play such as the overestimation of German air superiority at the time, or the overestimation of the level of destruction that strategical bombing could cause, or the overestimation of the Wehrmacht’s strength and morale, or the fact that Germany’s tank programme greatly benefited from the Skoda factories, but then again, people had to deal with the limited and flawed information they were given.

‘At the diplomatic and political level, the allies did indeed achieve their goals of buying time, mobilizing, as well as isolating Germany’

Turning to the present, it should first of all be evident that any analogy between National Socialist Germany, 1930s politics, and contemporary Russia is beyond ridiculous. Even if, in the unlikely scenario in which Putin harboured unlimited geopolitical ambitions to achieve, these objectives are all thwarted by the fact that Russia does not have unlimited military capabilities. In fact, one must seriously question the logic behind the statements that the ‘Russian bear’ can steamroll Europe—and, on the other hand, that Ukraine can win the war.

More importantly, I would argue this discussion ignores the role of nuclear deterrence (MAD) between Russia and the West, as both the UK and France carry a nuclear arsenal.

European leaders could certainly learn from the period—such as creating a strict time framework to build up military strength, improving industrial capacity through re-industrialization, propping up manufacturing, or minimizing external dependence on critical resources. Medium to small sized European countries should learn the age-old lessons provided by realism as vindicated from the interwar period and current international developments. Self-help and hard power are the only sustainable policies towards geopolitical relevance and national security. External counter-balance through alliances is an invaluable tool, but for the moment, current reality within EU circles means it has to take a backseat.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio has made it abundantly clear that we are for a shake-up in the international order. The USA is now focused on positioning itself in the most advantageous way in the new multipolar world; thus, it is certainly true that NATO as we know it will come to an end. A Sino–Russian split is highly unlikely; Russia does not have any strong reason to trust the West. Stable relations become a necessity for a sustainable coexistence between the competing poles. Of course, this does not translate to the USA not being aggressive towards China, but it changes the focus from one of global hegemony to one resembling tacit spheres of influence. Regarding the future of NATO in Europe, a lot is dependent on whether a minerals deal between Ukraine and the USA goes forward.

European countries now face a conundrum. Calls for the centralization of defence policy via the Commission are politically dubious at best, and will lack support from members, who are in favour of intergovernmentalist options—like they always have been. Poland seeks to maintain partnership with the United States and relies on a compromise between Russia and Ukraine. Greece wants to keep a special relationship with the United States in the eastern Mediterranean and continues following a strategical dogma of aligning itself with the major naval power. Hungary has managed to successfully invest in bilateral relationships that offers great benefits in a bipolar or multipolar moment; the question is whether the Sino–Hungarian partnership will cause problems between Hungary and the United States, furthermore, Hungary’s future relations with an even more hostile Commission and major member states that encompass different geopolitical goals.

Current European political leverage without US backing is minimal, nevertheless, individual member states, such as Hungary, Poland, Italy, Greece and others, can exploit opportunities from recognizing this reality: either by investing further in bilateral partnerships or by using political leverage within the EU to steer foreign policy discussions more towards their own security concerns.

If Europe wants to play any role in this new international system, that is shaped right within our own very eyes, a radical shift in leadership and policy directions is necessary. Recognizing that one way or another, the conflict in Ukraine bears more costs than benefits is fundamental. If the previously outlined facts are not taken seriously, then Europe is doomed to collectively experience a century of grand humiliation on the global stage.

[1] For an interesting analysis on the parallels between the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the crisis of the summer of 1914, see: https://mises.org/mises-wire/we-must-now-learn-lesson-1914-not-lesson-1938

[2] Norrin M Ripsman, Jack S Levy, ‘Wishful thinking or buying time?’, International Security, 33.2.

[3] Britain had only 100 hurricanes, no more than a dozen spitfires, and only 5 radar stations, which later proved crucial in winning the battle of Britain.

[4] For a more detailed outlook on the following, Adam Tooze’s The Wages of Destruction is an excellent book on the topic.

[5] Italy would only enter the war in 1940 after the outcome of the Invasion of France was beyond certain.

Related articles: