The Kádár regime’s secret police department responsible for internal counterintelligence (BM III/III) had numerous tragic, dark, or even absurd episodes in its relationship with the Jewish community—we’ve written about these several times on the Hungarian Conservative. Particularly shocking, however, are the reports concerning the Anne Frank High School, a Jewish high school, as these fundamentally involved minors as well. The documents related to the surveillance of the congregational high school—which have only survived in scattered form among other materials—offer a unique opportunity not only to study the Kádár regime and its antisemitism, but also to gain insight into the cruel mechanisms operating behind the mask of the so-called ‘soft dictatorship’.

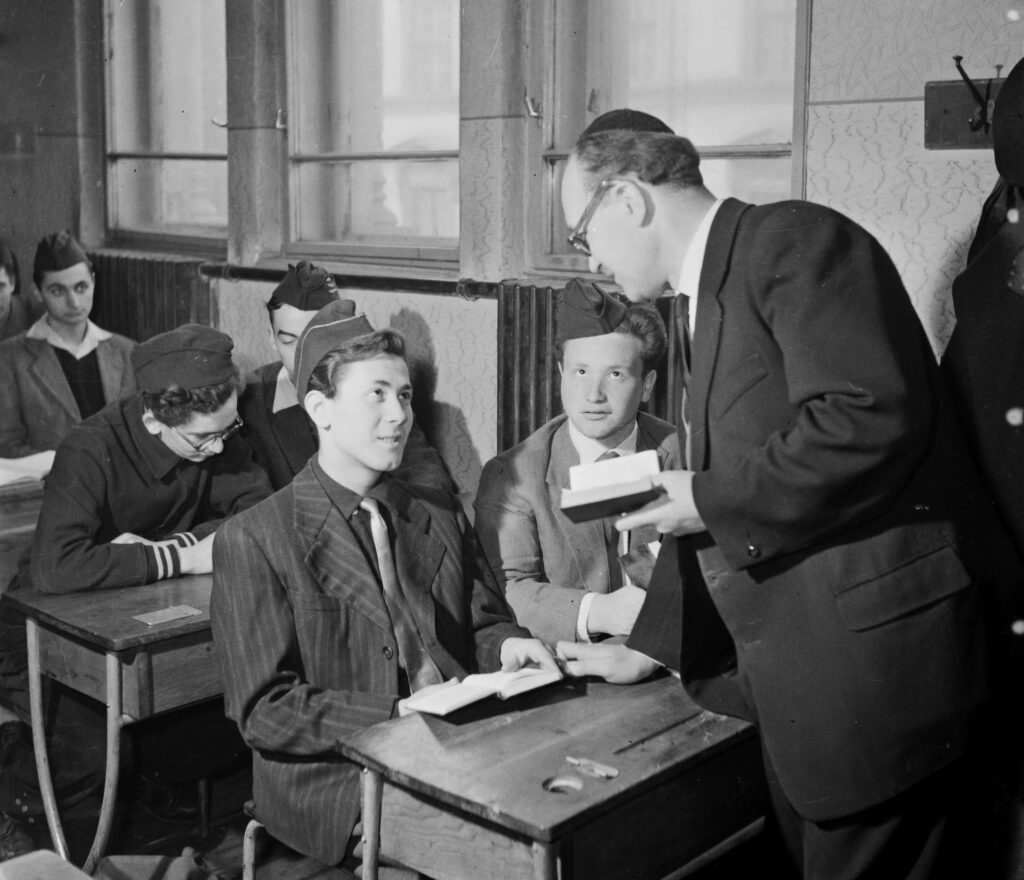

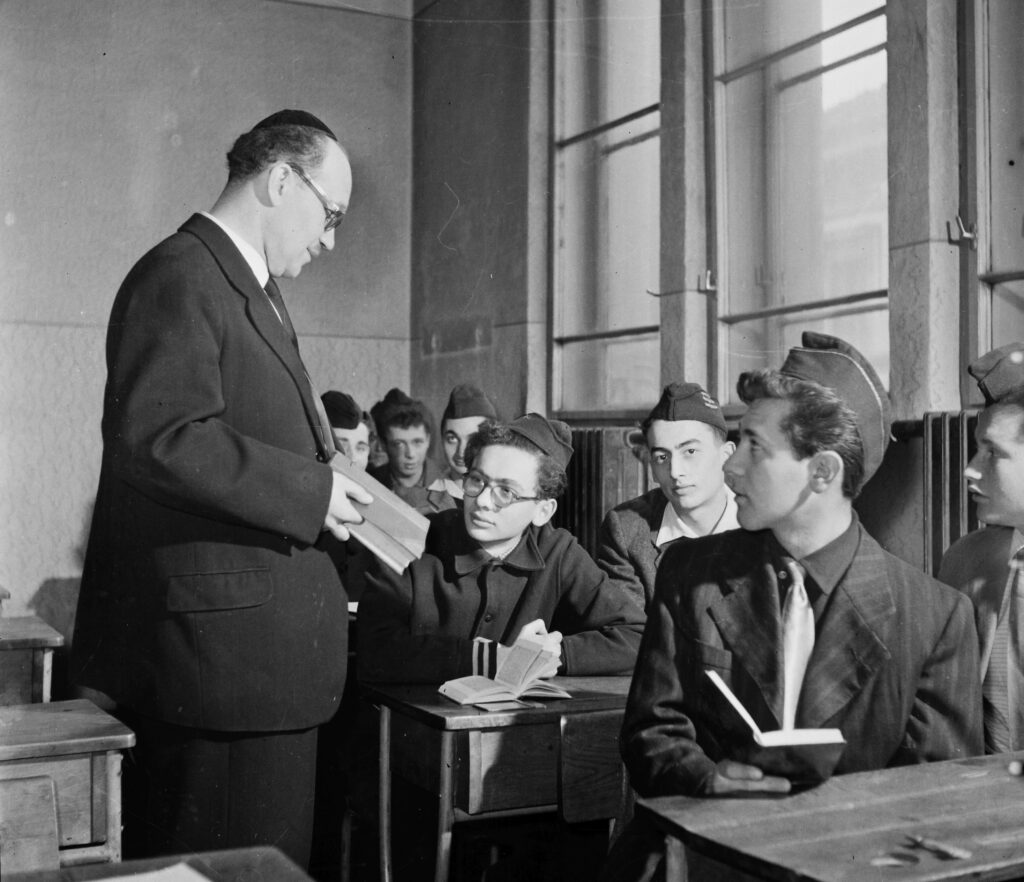

First, a bit of historical background on the Jewish high school is needed to fully understand the reports. Although there had been earlier efforts to establish such an institution, ironically, it was the wave of antisemitism following the collapse of the Austro–Hungarian Empire in 1918 that gave the final push. The Jewish high school opened in September 1919, initially housed in the building of the congregation-run school on Wesselényi Street, before the completion of its permanent home on Abonyi Street. Its first principal was Bernát Heller (1919–1922), a renowned Bible scholar and rabbi, and the mentor of Sándor Scheiber. Over time, the school also had other notable educators, such as Zsigmond Pál Pach, Miklós Szabolcsi, and Scheiber himself. In 1923 the school moved into the Abonyi Street building, but it was nationalized in 1952. As a result, the Jewish high school was relocated to the Rabbinical Seminary, and later became part of the Boys’ and Girls’ High School of the Budapest Israelite Congregation—which has borne the name Anne Frank since 1965, and since 1998 the name Sándor Scheiber.[1]

One of the main targets of the surveillance was Principal Jenő Zsoldos (born Stern), who had served as principal of the girls’ high school since 1939 (the boys’ and girls’ high schools were merged in 1959). Zsoldos was clearly well loved by the students. At his funeral in 1972 educator Mrs Miklós Fischl said: ‘The effectiveness of a teacher’s work is most reliably measured by the reactions of their students: his pupils responded with perfect resonance to his exceptional influence as a teacher. His impressive presence, strictness laced with gentleness, profound knowledge, and broad cultural sophistication were each a pathway to his students’ hearts.’[2]

Zsoldos came under the focus of the Ministry of the Interior’s III/III-2-a subdepartment as early as 1964, when a report titled ‘American Scholarships at the Jewish High School’ claimed that several instructors—including the principal—were receiving financial support from overseas, amounting to several thousand forints.[3] It likely didn’t help that Zsoldos had previously opposed the merger of the two high schools; his colleague, Rabbi Miklós Mandel (later Máté), the school inspector, even resigned from his position in protest. At the time, Máté—who would later play a significant role in the story—was clearly identified as an oppositional, Zionist-leaning rabbi. In the spring of 1961, the ÁEH (State Office for Church Affairs) refused to recommend issuing him a passport for travel to the West, stating that ‘Miklós Máté…sympathizes with those of Zionist orientation and with the Israeli embassy. He’s up in arms whenever he’s asked to do anything in service of our regime.’[4]

Plans were made to remove Zsoldos, but it seems there was no agreement on who should succeed him. With the agreement of the ÁEH, the state security turned its attention to Rabbi Ödön Singer, who at the time was serving as a rabbi in Kaposvár and Nagykanizsa. Singer had lived in Israel from 1956 to 1959, then returned to Hungary, and from that point on was considered a rabbi loyal to the regime—presumably the price he paid for being allowed to return. The proposal stated: ‘Given that there are Zionist teachers at the Jewish high school, it is necessary that after Rabbi Dr Ödön Singer is transferred to Budapest, we provide him with a teaching position at the high school, and later appoint him to the position of principal. Through him, we will have the means to gradually replace the Zionist-leaning teachers over time and install individuals with loyal attitudes in their place.’[5] He did not, in the end, become the principal.

To effectively take over the high school, it was clearly necessary to expand the counterintelligence service’s operational capabilities, which in turn required extending the surveillance network into the institution itself. In the second half of 1965, several recruitment plans were drafted by the Ministry of the Interior’s III/II-5-a subdepartment: ‘From a long-term perspective, we will select two or three individuals at the Jewish High School for study with the goal of recruitment. We will proceed with the recruitment of the appropriate candidate.’ And: ‘At the Jewish High School, we are studying the profiles of (xy) and (xy), both female teachers. The appropriate one will be recruited.’ In the end, it appears they abandoned the idea of recruiting the female teachers—all known agents who were active in the high school were men.[6]

Of course, Zsoldos wasn’t the only one to attract the attention of the Ministry of the Interior. One of the primary targets of the anti-Zionist (essentially antisemitic) campaign at the time was Sándor Scheiber, who taught religious studies at the high school. The Ministry waved around the following quote from the renowned rabbi like some sort of indictment: ‘Modern thinking is unworthy of the Jewish school because it accelerates and facilitates assimilation. Young people must be raised to feel guilty if they are unable to observe any of the holidays, dietary, or other religious laws.’[7]

Another person singled out was teacher Tivadar Szántó, who was said to have ‘ongoing contact with (Zvi) Shamir (Second Secretary of the Israeli Embassy—L B V).’ A note from the handler attached to the agent’s report read: ‘Tivadar Szántó, orphanage director and Jewish high school teacher, has an interesting embassy connection. This is the first time his name has come up as a contact with the embassy…We will confirm Tivadar Szántó’s personal data, run a criminal background check, and cross-check through Directorate III/I on the embassy case. We’ll also review our other network options, and have our network sources characterize him, if they know him.’[8] A translation of the counterintelligence jargon: they intended to check whether Szántó had any compromising information on file in the Ministry’s records, verify him through counterintelligence channels, find out whether colleagues knew him, and, if any agents had contact with him, request a profile.

The removal of those accused of Zionist sympathies occurred in the spring of 1965. According to the summary by the ÁEH, ‘during the organization of the Jewish Passover celebrations, a dispute arose between the principal of the high school, Dr Jenő Zsoldos, and Chief Rabbi Dr Imre Benoschofsky, as a result of which the principal became offended and submitted his resignation to the MIOK (National Representation of Hungarian Israelites). In solidarity with him, Deputy Principal Gyula Laub and teacher Dr Sándor Scheiber also submitted their resignations. These accidental events solved an old problem for us, as it is well known that the political and “educational” atmosphere at the Jewish high school was problematic.’[9]

However, there was nothing ‘accidental’ about it. The Ministry of the Interior described the same series of events as follows: ‘During the summer (sic! spring), through our network and operational combinations, with the agreement and cooperation of the ÁEH, the following individuals were removed: Dr Jenő Zsoldos, the principal, and his deputy. Politically reliable individuals were placed in their positions. Dr Sándor Scheiber, who taught religious studies at the congregational high school, was also removed and, starting from the new school year, he no longer teaches at the high school.’[10]

An interesting choice of words here is ‘through our network’—Rabbi Benoschofsky was not listed in the network’s registry, and there is no evidence that he was an agent. However, through his sister, who was indeed an agent, they likely had the ability to influence him. Moreover, there are documents suggesting that the Ministry of the Interior may have had compromising information that could have been used to blackmail him.

It is also noteworthy that Zsoldos’s resignation was initially not accepted by Endre Sós, the president of MIOK. As a 1967 report by the Agitation and Propaganda Department prepared for the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party Political Committee states: ‘Since the congregational elections, several individuals who were known for their excessive nostalgia for Israel and Zionist behaviour have been removed from leadership positions. Among them:…Jenő Zsoldos, the former principal of the high school, and Sándor Scheiber, who was removed from his position as a religious studies teacher at the high school. It must be noted that…Sós did not want to accept Zsoldos’s resignation and even tried to persuade him to stay. It was only after a firm intervention that Sós changed his stance.’[11] This was noted by the Ministry of the Interior back in 1965, and it was treated as distinctly negative information, despite the fact that Sós himself was one of their agents.

Zsoldos’s successor was, in the end, not Rabbi Singer, but one Lajos Davidovics, who, although he was not listed in the network’s registry, was appointed to the position explicitly upon the Ministry of the Interior’s recommendation. According to the ÁEH, ‘The appointment of Lajos Davidovics was primarily proposed by the officials of the Ministry of the Interior, with whom he has been acquainted since his time as a member of the militia (munkásőrség, workers’ guard). As his attached biography shows, he would be politically suitable to fill the principal position, though it should be noted that he will only obtain his secondary school teaching diploma this fall, after successfully passing his state exams.’[12]

According to his attached biography, Davidovics was indeed a reliable comrade: he had been a party member since 1947 (his father had been an illegal communist since 1932, and his sister since 1938), and furthermore, in 1956, ‘during the counterrevolution, I served in the VIIIth District militia as a workers’ guard and was also the interpreter for the Soviet Command in that area. For my participation in the armed suppression of the counterrevolution, I was awarded the State Decoration for Workers’ and Peasants’ Power (Munkás-Paraszt Hatalomért kormánykitüntetés).’[13]

A conflict soon arose between the new leadership and Scheiber. According to an October 1965 report, Scheiber ‘protested indignantly against Lajos Davidovics’s intention to take the gymnasium students’ youth services out of the rabbinical seminary’s synagogue and to organize a separate youth service for the gymnasium students at the orphanage.’[14] An intriguing detail is that a copy of the report was filed in a folder titled ‘Jewish Gymnasium’, suggesting that a separate dossier was maintained to monitor the institution. Unfortunately, this file has not been preserved. It is also known that Zsoldos continued to be monitored after his removal. Since he regularly met with a few friends, including the elderly scholars and teachers Samu Szemere and Mór Léderer, at the Kékes restaurant, their personal data was collected, a criminal background check was requested, and they were also monitored by agents. The reports about them were placed in a folder codenamed ‘Old Zionists’, but unfortunately, this dossier has not been preserved either.[15]

The authorities were likely not too satisfied with Davidovics, as he left after barely a year. His successor, as acting director, was his former deputy, Magda Timár. A more lasting legacy of his was that, at Davidovics’s initiative, the school adopted the name Anne Frank. In 1967 Rabbi Miklós Máté became the principal of the school. Under his leadership, the institution began to slowly decline, but at least in terms of politics, it seemingly started to meet the expectations. The school’s 1969 work plan, written by Máté, can be found among the ÁEH documents today.[16] According to this, there were 78 students attending the institution at that time. ‘In the teaching of every subject, we use the available opportunities to deepen the feelings and duty of patriotism and proletarian internationalism…Religious education is not an exception among these lessons.’ In the report, he mostly defended his teachers, describing everyone as a capable person, except for Tibor Kuti, a mathematics and physics teacher, who was ‘the greatest burden of our school’. Although learned and serious, he was not suited for the position, and ‘his educational work can be considered null’. (We will return to this remark later.)

In addition, he attached to the work plan a draft for ‘deepening patriotic education’. It is worth quoting in more detail because Máté reflected on the conflict between loyalty to the socialist homeland on the one hand and Judaism and Zionism on the other. ‘We live in a socialist country, whose principle is materialism, while the principle of religions, including Judaism, is idealism…As a result of this fact, there may be conflicts in the souls of the students. However, in the teachings of our religion, there is so much in common with the ideals of socialism that this aspect can be safely omitted. I am thinking here of truth, love, respect for human life, the blessing of work, peace, bringing a happier world, and the categorical condemnation of war.’ Additionally, the ‘question of Zionism’ arises. ‘Hungarian Jewry has always, throughout its history, considered itself completely Hungarian…only a small fraction of Hungarian Jewry considered themselves Zionists.’ Of course, many people have relatives in Israel, and there is also the biblical connection to the Holy Land (‘I would rather call it interest’). ‘The question that arises, therefore, is this: What is the Anne Frank Gymnasium doing, or what does it want to do, so that the students who attend there, the potential future leaders of Hungarian Jewry, will be loyal sons of their homeland, free from any harmful influences, love it, be proud of its achievements, participate in all its work, and share in its joys and its pains?’ ‘In a few sentences, I would like to outline our plans. I start with religious education. From the Bible…I discuss with my students the tasks awaiting us in the direction of the homeland. Those that are related to Israel, I neglect.’ Máté considered it important to teach Hungarian Jewish authors whom he regarded as assimilationists, such as József Kiss (although Kiss was a more complex poet and not hostile to Zionism).

Although it might seem like a minor issue, which poet the students learn poems from, the truth is that the authorities were very much interested in this. When, in the early 1960s, a female student recited a poem by Chaim Nachman Bialik, a Zionist Hebrew poet, instead of the prearranged poem at a provincial event, the matter led to an undercover investigation. The girl—probably under another pretext—was also summoned for questioning at the police station in the 5th district, where they asked her about her teachers. The agent who reported on the girl was assigned the task of ‘getting to know more details about the activities of the Zionist youth group gathering at the Jewish gymnasium.’[17]

The counterintelligence service not only monitored the teaching staff but also the students. Interestingly, it was handled by the III/I-1 unit of the Ministry of the Interior (task: ‘intelligence gathering against the USA and international organizations’), meaning that it was not internal counterintelligence but external intelligence that dealt with the matter. According to an internal correspondence from September 1964: ‘I ask the Department Head Comrade to send the list of the graduating students of the Budapest Jewish gymnasium to the III/I-1 unit.’ Within this, for a few selected individuals, detailed information was requested regarding ‘their personal and character traits, political stance, and possibly foreign connections.’ The few young people were all born between 1941 and 1944.[18]

In addition, personal data (name, birth year, mother’s name, address) of all class heads and their students were requested in several years. These were handled by the Ministry of the Interior’s III/III-1-c unit. The lists for the 1966/67, 1970/71, and 1975/76 school years have been preserved, but it is a logical assumption that such lists were submitted every year.[19] Next to a few names, small lines were added with pen, but the meaning of this is unknown, as among the names are both surveilled individuals and others whose names do not appear again in the documents. The data was provided by one of the recruited teachers. The agent was not only asked about the students but also about the parents and colleagues. The agent clearly tried to protect their colleagues, even reporting about the aforementioned Tivadar Szántó, saying that ‘his teaching work is mediocre. He is of Orthodox religion, but not really. Rather, he wants to appear as such. Politically reliable.’ Of course, what constituted valuable information and what did not was not decided by the agent but by the handler. A note at the bottom of the report reads: ‘The report has operational value; the agent carried out the task according to our instructions.’[20]

The agent also reported on the students and their parents. In 1971, for example, we can read the following in one of the reports: The student P A ‘lives with his widowed mother…They manage well on her salary…He shows little interest in political matters.’ In the case of H Gy, ‘the father is a watchmaker, earns well. They have a two-room apartment…The boy is a bad, careless student…He is not very interested in foreign politics.’ In T T’s case, however, ‘very decent parents…The father has a well-formed, well-founded opinion about everything. He loves his country, sees Israel’s role in the politics of the superpowers.’ The agent found excuses here as well: ‘I want to note that I encountered no hostility against the Soviet Union. Everyone understands the fact that they owe their lives to the Soviet army. Critical remarks were made, but they reflect the question of how a superpower can oppose such a small, long-suffering nation like Israel. However, they clearly see that this is a political issue arising from the conflict between the two superpowers.’ The handler was not satisfied with this. His comment reads: ‘The report does not reflect the political issues raised during the conversation or provide adequate answers. The informant, taking a protective stance, lists general, well-known political facts. The information regarding the families is perhaps partially usable.’ Therefore, the following orders were given: ‘He should change his rigid behaviour in the future,’ and understand that ‘we are primarily interested in those persons in whom we observe Zionist manifestations and who are suspected of engaging in hostile activities.’[21]

Of course, what constituted a ‘Zionist manifestation’ was again a relative matter. The reports were not only provided by recruited teachers but also by recruited high school students. One agent, who was in his mid-teens when he was recruited, was likely blackmailed due to his well-known homosexuality. This student reported on other students as well. After the Six-Day War, when Hungary broke off diplomatic relations with Israel, the agent reported on the mood of his classmates. ‘The break in diplomatic relations with Israel is a topic that strongly occupies the students of the high school. Despite the end-of-year exams, during break time, groups of five–ten students discuss the events. In these conversations, they take a stand in favour of Israel and make critical statements about the Hungarian government. Some statements include that the Hungarian government did not speak up during the 1944 deportation of 600,000 Jews, yet it is now shouting about the fate of 100,000 Arabs.’ If anyone dared to appear with a Star of David pin on their coat, he quickly reported their name to his handler.[22]

Unlike the recruited teacher, this young agent no longer covered up for the teachers critical of the regime. According to a 1968 report, Mrs Fischl, the biology-chemistry teacher’s ‘pedagogical work is sometimes harmful. For example, when teaching materialism, she says we should read and learn from the book because she doesn’t have anything to say about it.’ Tivadar Szántó, the history teacher’s ‘pedagogical work is of low quality and unserious. He is well-known among the students as a Zionist. Though occasionally, such as during the Middle Eastern war, he tries to create a positive impression by making statements like he sympathizes equally with every Arab and Israeli soldier who dies in the war. This caused hatred against him among the students.’ Regarding Tibor Kuti, the teacher who Máté had also criticized, the report states that ‘his pedagogical work is repulsive, constantly reactionary…at every political event, he only highlights the negative side to the youth.’ These comments should be read with a pinch of criticism, as it is clear that the ‘Zionist’ teachers were portrayed as untalented, poor educators.[23]

The surveillance of the Jewish high school is an exemplary case of the repressive policies of the communist dictatorship, in which innocent, sometimes underage individuals were harassed and monitored in a manner that would be considered a severe violation of rights by today’s standards. Despite over a decade of surveillance, the Ministry of the Interior never managed to uncover a single substantive case, and despite the involvement of counterintelligence, there was no proof that any of the young people were spies.

Under Máté’s leadership, the high school began to decline slowly. According to a 1976 summary, by this time, only 11 teachers were educating a total of just ten students. No new class was launched in that year. The possibility of closing the institution arose, and the MIOK was open to this, but the ÁEH concluded that ‘the closure would cause international political complications.’ ‘It was agreed with the MIOK leadership that no new student applications would be initiated, and the school would be gradually phased out within three to four years. The current principal of the high school is Rabbi Miklós Máté. He is a progressive personality, and he fully adheres to the instructions of the Ministry of Education regarding the high school,’ according to the ÁEH summary.[24]

The regime appreciated Máté’s activities. In 1979, Imre Héber, President of the MIOK, nominated him for the National Peace Council’s (Országos Béketanács) award, saying that he was ‘an outstanding figure in the Hungarian rabbinate’ and that he ‘encourages and educates the students of his school to actively and militantly stand for socialism.’[25]

Despite Máté’s efforts, the institution remained open. Today, it operates in a new building, bears the name of Sándor Scheiber, and according to its website, in the 2020/2021 school year, 480 students’ families chose the institution.

[1] Erdei Hajnalka, Marton Péter, ‘Élet a zsidó gimnáziumban’, História, 1988/2-3, 61–62.

[2] Évkönyv – Magyar Izraeliták Országos Képviselete, 1973–1974. Ed Scheiber Sándor, Bp, 1974, 230–231. Some documents on Zsoldos’s surveillance were published by: Kovács András: A Kádár-rendszer és a zsidók, Bp, Corvina, 2019, p. 339, p. 356, p. 365.

[3] Állambiztonsági Szolgálatok Történeti Levéltára (ÁBSZTL), 3.1.5. O-17169/1, 129.

[4] Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Országos Levéltára (MNL OL), XIX-A-12-a, 151. d. 2–25/1961.

[5] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/1, 167.

[6] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/1, 245, 379.

[7] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169, 239.

[8] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.2. M-37809, 319–320.

[9] MNL OL, XIX-A-21-d. 11. d. 0020-3/1965.

[10] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/1, 324.

[11] MNL OL, M-KS 288.f. 22/1967/1-22.ő.e. 20.ő.e. 41–51.

[12] MNL OL, XIX-A-21-d. 11. d. 0020-3/1965.

[13] Ibid.

[14] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-13558/2, 84.

[15] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.2. M-37809/2, 74.

[16] MNL OL, XIX-A-21-c. 87. d.

[17] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/1, 207 and ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-13772/1, 38.

[18] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/1, 215, 219.

[19] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/5, 28–34, 38–45, 48, 51, 56, 77, 107.

[20] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/5, 87–88.

[21] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/5, 73–75.

[22] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.2. M-37477, 24.

[23] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.2. M-37477, 31.

[24] MNL OL, XIX-A-21-c. 87. d.

[25] MNL OL, XIX-A-21-c. 89. d.

Related articles: