The following is an adapted version of an article written by Orsolya Ferenczi-Bónis, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

Good Friday is the day commemorating the death of Jesus on the cross, a time of great mourning, observed with total silence, the fires extinguished, mirrors covered with a black shroud, and all clocks stopped. Early in the morning, families would walk to church, women and girls in black mourning dresses; white in some regions. It was a strict fasting day: many people only ate a little bread in the evening, while some consumed only three grains of wheat and three drops of water.

Folk beliefs were also associated with the day. For instance, we know from Hungarian Folklore (Magyar néprajz) that on Good Friday, people did not curse because they believed that if you cannot stop yourself from cursing, you will be struck by lightning.

They did not do any work related to animal husbandry or certain kinds of agriculture, because Good Friday was considered an unlucky day. It was also forbidden to bake bread because it was believed that it would turn to stone—but this belief may also have been based on the fact that, since no fire was lit on Good Friday, no bread could have been baked.

‘On Good Friday, people did not curse because they believed that if you cannot stop yourself from cursing, you will be struck by lightning’

On the other hand, it was worthwhile to leave the clothes and handwoven items out to air that day, because it brought blessings to the wearer; and those who bathed before sunrise on Good Friday were not affected by diseases. The water was believed to have powers of preventing illnesses, of purification, fertility and beauty. The water brought at dawn on Good Friday was called golden water, rose water or raven water, referring to that the ‘raven was washing his son’ at that time. Eliminating worms was also associated with purity and purification. Furthermore, it was believed that by sweeping around the house, witches would be driven away.

Processions, Tableaux, Passion Plays

On Good Friday, the suffering and death of Jesus on the cross was commemorated with mystery and passion plays, processions and songs. These often drew on apocryphal tradition, legends and visions, including details such as Jesus being thrown into the river or having his tongue pierced with a thorn. Fairground entertainers told the story of Jesus Christ’s bitter agony to the illiterate by illustrating each moment with drawings and illustrations on sticks.

In Sándor Bálint’s Christmas, Easter, Pentecost: Traditions of the Great Festivals in Hungary and Central Europe (Karácsony, húsvét, pünkösd: A nagyünnepek hazai és közép-európai hagyományvilágából), we can read that the suffering and persecution of Jesus became the source of many myths explaining natural phenomena. One of these is that Christ fled under a poplar tree, but it refused to help him out of fear, so Christ punished him—ever since, the leaves of the poplar tree have been shaking.

‘Christ fled under a poplar tree, but it refused to help him out of fear, so Christ punished him—ever since, the leaves of the poplar tree have been shaking’

The Lombardy poplar did not shelter him either, but rather reached up—it has been growing ever since. The turkey oak failed him as well, so Christ cursed it to be struck by lightning: since then lightning has struck this tree the most often. The birch tree, on the other hand, has covered him nicely—thus, its branches have been easy to bend ever since.

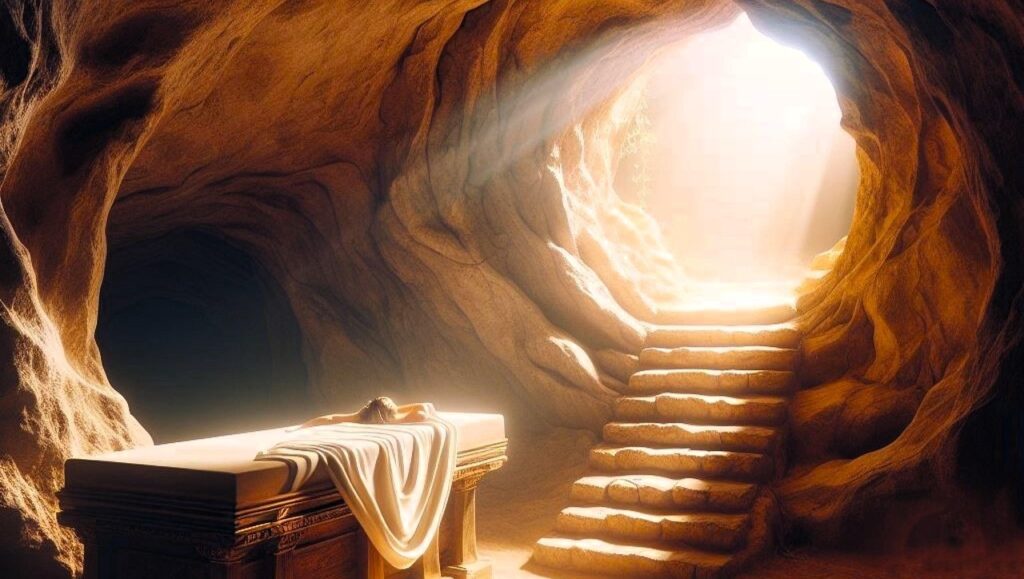

The burial and wake of Jesus was part of the popular liturgy, with the Stations of the Cross and the holy tomb of the church as a reminder of the sacrifice. A special tradition was the so-called black mass or funeral mass, during which vigils were held throughout the night, prayers were said, the sorrowful reading was performed, and Marian hymns of grief were sung.

The Reproduction of the Tomb of Christ in Jerusalem

We can read in Sándor Bálint’s book that the holy sepulchre, or the tomb of the Lord, is a specific liturgical development in Hungary and Central Europe. Originally, it consisted of the cross, which was covered with white linen cloth, and even with vestments and a stole, while mourning songs were sung. It was sprinkled with holy water, smoked, as it was the custom at funerals, then a stone was placed on it, which was then sealed, and a guard was placed beside it.

The guard of honour around the tomb was once the privilege of a guild or pious society; the participants were called the soldiers of Jesus. The tomb was decorated with rosemary, the flower of undying love, but it was also customary to decorate it with glass globes. These were filled alternately with white and red wine, and a lighted candle behind them illuminated the bottles.

The Most Beautiful Domestic Holy Tomb Relic: The Lord’s Coffin from Garamszentbenedek

The Christian Museum in Esztergom preserves the most beautiful relic of the Hungarian tradition of sacramental worship. Known as the Lord’s Coffin, it comes from the Benedictine abbey church of Garamszentbenedek. It is the only surviving late medieval example in Hungary of a type of wooden freestanding Gothic holy tomb, rare in Europe.

The canopy over the coffin symbolises the heavenly Jerusalem to come. Between the pillars supporting the canopy is the figure of the twelve apostles. Beneath it is the sarcophagus of Christ, the sides of which are decorated with biblical scenes and figures.

The tomb also included a statue of Christ with a movable arm, which was taken down from the cross during the ceremony, placed in the coffin, and kept there until the dawn of Easter. On the day of the resurrection, the statue was again removed from the tomb and the empty coffin was paraded in the church. This statue, also of medieval origin, can still be seen in Garamszentbenedek.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.