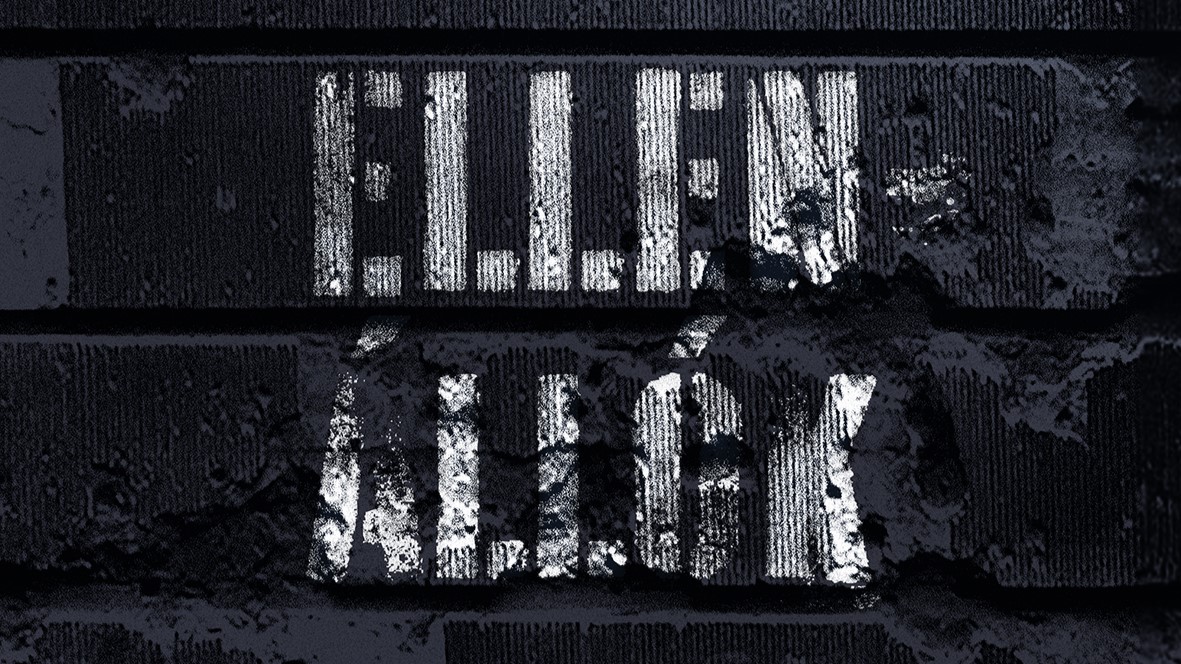

An exciting, thought-provoking publication has been released by the Committee of National Remembrance (NEB) titled Resisters 1944–45 (Ellenállók 1944–45). This particularly beautiful, richly illustrated volume briefly presents the life stories of 104 resistance members, accompanied by the insightful narration of expert historians. As the editors—Ákos Bartha, Réka Kiss, and Nóra Szekér—clarified in their introduction, they did not aim for completeness in selecting the individuals featured, but sought to demonstrate the diverse forms resistance could take.

The people featured in the volume are those who, in some way, took part in the anti-Nazi resistance movement that emerged in Hungary during the Second World War. Following contemporary trends in international historiography, the book includes not only armed resistance but also intellectual opposition—articles and leaflets, anti-German and anti-Arrow Cross (nyilas) propaganda, symbolic acts, bureaucratic resistance within the public administration, as well as efforts to save Jews, including self-rescue.

The authors’ primary aim was clearly to present as many individuals as possible who had previously received little attention in the public discourse on 20th-century Hungarian history, or who had remained entirely outside the canon of historical memory. The history of Hungary’s non-communist resistance groups was a forbidden, and even later merely tolerated, subject before the regime change of 1989—and for years after the fall of the dictatorship, it remained among the neglected topics.

Naturally, given the nature of such a project, not every act of resistance could be associated with identifiable faces. One well-known example is the story of ‘Little Warsaw’ between October 15–17, 1944, when Hungarian Jewish forced labourers at Teleki Square of Budapest opened fire on the Germans and the Arrow Cross; their resistance could only be crushed with the deployment of German tanks. But since the names of these resisters are unknown, their stories could not be included in a volume built around personal histories.

‘This entire tangled, difficult-to-unravel, complex, and multifaceted story makes up the whole of the Hungarian resistance’

The volume does not claim that the individuals featured within its pages led spotless lives or were liberal democrats. But perhaps national memory has reached a point where we are open to the idea that those who took part in the resistance were not always people who made the right decisions, or were necessarily successful, or politically colourless, odourless figures. Even so, researching, uncovering, and presenting their life stories remains both legitimate and necessary. Of course, the resistance also includes those far-left figures whom communist memory politics inflated or portrayed in a disproportionate light. This entire tangled, difficult-to-unravel, complex, and multifaceted story makes up the whole of the Hungarian resistance.

The core of the volume, following the introduction, is made up of these life stories. Here we find familiar names such as Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky, Pál Demény, János Kiss, Áron Márton, as well as Károly Lázár and Hanna Szenes. But the book also brings to light lesser-known figures like István Vasdényey, Kálmán Zsabka, and Antal Sigray, along with others whose names had long faded into obscurity. It is genuinely fascinating to read about Gyula Magyary, a priest recruited by the OSS who, under cover, made his way to Buda Castle to deliver a message from the Allies to Miklós Horthy; about Kálmán Rátz, a former Arrow Cross politician who became an anti-German activist; or about István ‘Potya’ Tóth, the legendary footballer and coach of Ferencvárosi Torna Club, who took part in the resistance, was arrested for it, and executed in the courtyard of the Interior Ministry’s building in Buda Castle.

The book Resisters 1944–45 is, overall, a significant achievement, and its quality is undoubtedly enhanced by the fact that the editors secured contributions from several prominent, highly respected historians—such as Balázs Ablonczy, Pál Pritz, and Sándor Szakály—to write some of the biographies. Of course, many more names could have been included, and there will inevitably be debates about why certain individuals were featured. Yet the reader finishes the book with the reassuring sense that, at long last, there is now a serious, carefully crafted publication that does not speak solely of the heroics of communist partisans, but also of the courageous stands taken by Hungarian men and women who believed in other ideals.

Related articles: