A prolific author of fiction books and poetry, translated into a number of languages worldwide, Dániel Levente Pál is the director of the literary division of the Petőfi Cultural Agency (Petőfi Kulturális Ügynökség). He has worked in journalism and publishing, theatre and circus, has travelled extensively and has studied and lectured at prestigious universities abroad. As a polyglot who is passionately curious about different cultures, he has devoted himself to the promotion of contemporary Hungarian literature abroad. We spoke with him about the work the division he heads is doing, about the importance of bilateral cultural relations and the universal language of literature at the Frankfurt International Book Fair in October.

When was the Petőfi Cultural Agency founded, and what is its mission?

We started preparing the agency in 2019, still under the wings of the Petőfi Literary Museum, and we were able to establish it at the end of 2019, beginning of 2020, when the pandemic hit us right away. We work in three major areas. One is the promotion of works written in the Hungarian language and of authors writing in Hungarian in Hungary and across the border, at all levels of education, from elementary schools to secondary schools and universities. We also strive to provide contemporary authors with as many opportunities as possible to show themselves. On the one hand, there are events in the capital, there are various literary fairs and cultural days, and then we have festivals in the countryside, like the Valley of Arts, where we either have our own stage, or we pay for and manage stage classes, and then we put different authors there. This happens in Hungary as well as across the border, in Transylvania, Vojvodina, and Upper Hungary [the parts of today’s Western Slovakia that used to be part of Hungary.]

Our other activity is exporting Hungarian-language literature abroad, in translation. Our work is needed because a Hungarian author who does not speak a foreign language or doesn’t have actively maintained foreign relations or doesn’t have the talent for self-management has little chance of getting published abroad. I will give you an example, István Szilágyi, one of the best contemporary Hungarian prose writers, aged 80 plus, but even Imre Oravecz, they have very few foreign language editions, especially István Szilágyi, which is a shame.

Our relationship with language departments of various universities is also getting better and better. In August, there is an annual conference where teachers of Hungarian as a foreign language from all over the world are invited. There are 150-200 participants there every year, and at one point I told them that I would be happy to give a presentation about what the agency can offer them, what we can share about contemporary Hungarian literature. And since then, the first half a dozen joint programmes have already been implemented, in Zagreb, Rijeka, Ljubljana, Barcelona, Cassino, Naples, Brussels, Curitiba (Brasil) and in the United States. The participants came from Chisinau, from Madrid, Krakow, Warsaw, Sofia and Belgrade, but also from other continents, from all over the world.

These people get to know a Hungarian author up close, who signs the book on the spot.

Our third activity is building bilateral relations. That is why we organize the international writers’ residency program, an online magazine for translated literature (1749.hu) or a poetry book series of contemporary foreign poets, and also masterclasses and fellowships. Most recently, we organized a Turkish fellowship. We have learned from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade that there will be a Hungarian cultural year in Turkey in 2024, so that’s what we’re working on now. We invite Turkish publishers, Turkish agents, Turkish festival organizers, we introduce them to the entire Hungarian publishing scene. To give you another example: the other day I had a discussion with Egyptian colleagues that in 2025 Hungary could be the guest of honour at the Cairo International Book Fair which is the largest book fair in the Arab world.

We also organize publishing masterclasses, with lecturers who are experts on how to be included in the international blood circulation of literature works. In September, we invited Katharina Loix van Hooff, a German French literary journalist and book publisher, who was previously, for four years, the international literary editor of the long-established Gallimard publishing house, and more recently has worked with the Les Argonautes publishing house. Her new project is the development of a social website processing European novels, which partly creates a community with its interactive interfaces, and partly functions as an informative website with its informative elements. I think that all such knowledge and experience are important for Hungarian publishers: they should start thinking in much broader perspectives and horizons, either about themselves or about their authors.

What is the significance of the Frankfurt International Book Fair for Hungarian authors and for the promotion of Hungarian literature?

Hungary has been here in Frankfurt for more than three decades. We have always had a strong Hungarian presence, with a large Hungarian national pavilion. Here in Frankfurt, several Hungarian publishers come to sell and buy rights. We are trying to boost that process through tenders on the one hand, and organization on the other.

Frankfurt is important because it is one of the heart chakras of literature trade and agent activity. This is a rights trading fair. Publishers and book agents come here, even a few days before the fair, to conduct as many closed negotiations as possible, to show each other their publishing portfolios and novelties, to draw attention to the fact that someone will soon be made into a Hollywood movie, for instance, and that’s why it’s worth buying the rights, and so on and so forth.

Our agency does not represent one particular publisher, we inform. We inform the professionals about the upcoming trends, waves and voices of the Hungarian literature, and of course about who we are, that we have many products, such as grants and an international writers’ residency programme; we publish The Continental, an American literary magazine with a strong focus on Central and Eastern European literature, and that we have been a co-organiser of the PesText international literary and cultural festival for four years. Some people find us by accident. Earlier today two ladies from the International Bookfair of Taipei came and explained that there is always a European stand there, which we had no idea about, and they would welcome us there as co-exhibitors.

You know, the German-speaking line was always important for the Hungarian intellectuals and writers, we belonged to the same empire, even a hundred years ago. Then this relationship was not completely severed until the World War, and after that the strong relation with the GDR survived. From the eighties of the last century, German literature meant the West for most Hungarian authors: publishing in German meant, and perhaps still means today, that you entered the international literary circulation. What for Romanians was the French language and Paris connections, for us Hungarians was the German language and Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Berlin.

Even though more and more Hungarian writers speak excellent English, the United States is too far,

in some respects, but Germany and the German literary life are close, also considering the fact that the road to the Nobel Prize for literature starts there.

So, there is this Austrian-German connection, and many of our really grand old writers have been translated into German. It was more of a generational thing, but it’s still the case today. They knew German very well. The generation of the ’80s, Péter Esterházy, Péter Nádas, and Imre Kertész are very well known in Germany. The fairs in Leipzig and Frankfurt have always been the most important, to achieve some international recognition, and then things may move on from there. Now the American line has also appeared, with László Krasznahorkai, but the main direction has always been Germany, because this is really the heart chakra, and everyone is here.

We also have printing houses like Alföldi or Kner here, and there are two or three other printing companies present as well, who are hunting for German and European customers. Those beautiful books, albums, let’s say printing industry masterpieces, are displayed, to show that these printers can make such beautiful books, and at a much lower price than their competitors. So, the printers say: why produce it in China when we can, too? The big Hungarian printing houses do a lot of business here.

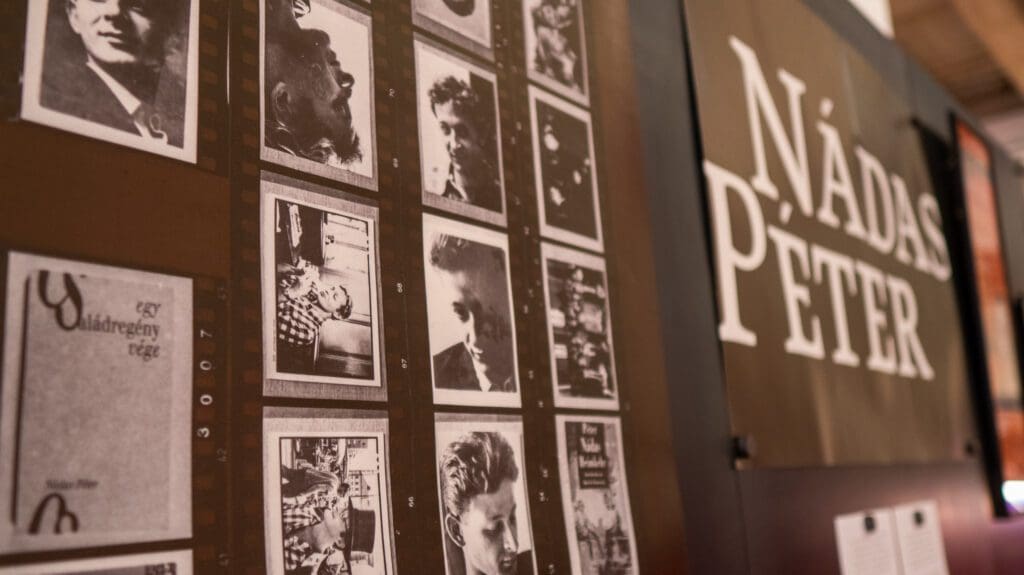

In addition, Péter Nádas turns 80 this year, and half of Frankfurt is talking about him, his new book has been published, so he is an amazing world star of Hungarian literature, especially here in Germany. He has been a potential Nobel-winner for more than a decade. We have also made a micro-exhibition for the round anniversary of his birth, which attracts attention. I saw that many people stopped, took photos, looked through the rare books and theatre posters of the plays based on his books that we displayed. They looked at them, and they got a new type of experience about who this person, Nádas, really is. He is on the front page of the daily newspapers even now. The biggest German newspapers are lining up to get an interview with him. He really is an 80-year-old rock star of almost unapproachable status, a Roger Waters of world literature.

This fair has about half a million visitors, and it is already a success if someone takes home one Hungarian book, if somebody takes a Hungarian author off the shelf, because our competition here is everybody else’s literature. We are here to make it happen that people fall in love with a Hungarian author, because if they give a chance to a book, they will continue to look for that author. It doesn’t matter if it’s Sándor Petőfi or Sándor Márai or Magda Szabó, or one of the young talents: what matters is that it’s Hungarian.

And so, on the last day of the fair, I can proudly say that yesterday a German book influencer ranked our stand among the five most beautiful pavilions of the fair.

Societies in Europe and in the United States are becoming increasingly polarized, with ideology-driven culture wars raging in many countries. Is that type of polarization, which could be somewhat simplistically described as left-liberal versus conservative, reflected in the literary world as well in your opinion?

The way I see it, the world has overcome this right-left division in literature. These discussions are only important to us, Hungarians, they are our internal affairs. Frankly, the opposite is also true: if I am impressed by a good Hungarian or foreign novel, I am not interested in the biography of the author. I don’t care whether they cheated on their spouse or not, who they voted for, or in what literary or political battles they took part.

In the past 15 years, I have held many lectures presenting Hungarian literature and culture in the Far East and Latin America, Europe and North America. Everywhere I talked late into the night with my hosts, and I noticed that when we start talking about politics, attention takes the place of attacks. I listen with interest to matters of Brazilian domestic politics, or the arguments and counterarguments of the American Republican-Democrat divide, or the political aspects of the difficulties and momentum of a country moving forward from its (post)colonial status. And they are curious about the Hungarian perspective. When you move around the world, everything becomes a perspective, a geopolitical perspective. How the same world political or cultural event is perceived from where you live, in the political or cultural context in which you socialize or move around on a daily basis. It is no coincidence that in many countries the ‘how are you?’ question is immediately followed by the ‘where are you from?’ question.

If I go to a book fair, the ideological scale is very wide, everything from A to Z can be found here, and it is refreshing that there is not just one idea, not one view.

If you travel a lot in the world, you will realize that the world is very colourful and that it is very accepting,

and not as exclusionary as it seems on Facebook. It is not that artists are isolated or excluded as it may appear in press reports. But of course, individuals have completely different preferences, prejudices, and opinions. When you go to someone’s house, they don’t first ask who you voted for, but when you’ve had dinner, talked about everyday things, started drinking wine or beer, more sensitive topics come up. If appropriate, a discussion will start about them. A discussion where the parties accept each other’s points of view and treat each other with respect. Of course, the debate can get heated, but if intellectuals come together, people with similar, more complex thinking, then it’s a good debate, time well spent, and not at the level of newspapers or social media.

The world is not a shop window, the reader is not a shop window, and it is also true that the world is diverse, that you too have different kinds of prejudices. You prefer to read someone who writes on a topic and from a point of view that is close to you. And you’re less likely to read someone who is not. That’s it. The same applies to publishers, professional readers who write reviews, recommendations, proof-reader reports, and translators. Everyone likes to spend their time with what is closest to them.

But even within a country, one encounters diversity. In Sao Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, the biggest cities of Brazil, with such a liberal society, you have a strong trans scene, for example. And then you go up north, which is basically a right-wing, conservative, deeply religious part, where you meet completely different people. However, you can take the same Hungarian author here or there. But again, Brazil is a quasi-European country. It is totally different in a Muslim country. You have to go there with great empathy and openness. Three of my books have been translated into Arabic and published in Cairo. Since there are erotic scenes in all of them, I was asked to consent to certain parts of the text being changed or omitted with my approval, because the sensibilities of the readers there cannot be offended by certain explicit dialogues. At most, we laughed with the translator about what the sensitive sentences ended up being replaced with. Let’s say in the original version the hero took off his trousers, this had to be rewritten as ‘he took off his jacket’; we had a lot of fun with that. That’s how the fuck turned into a kiss. I was not offended: the more restrained text is even more erotic, leaving more to the reader’s imagination. But there are those who say no to that and refuse to rewrite the original. Why do I need to be respectful to another culture’s sensibility, they ask. That is a choice, but if the author says, I’d rather provoke them, then they will say well, I don’t need that.

And just one step away are some of the heated debates of the last couple of years, for example, what took place around Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Winnetou. I think the more different voices have validity and weight, the more perspectives and truths prevail, the more conflict there is. The more colorful the world we live in, the more shadows there are.

But the history of culture has always been a game of light and shadow, it’s up to us whether we fight it with words or weapons.

There are always fashions, there are always ideologies, there have always been, and always will be. Art managers and artists tend to ride the waves of fashion on a surfboard. But no matter how colourful a part of it is, the majority of society always wants to be somewhere in the middle. Eat, drink, have fun, live normally. They accept many things as private individuals, as a family, and as a micro-community, but they can decide, because they have the freedom to do so, to follow a certain course or not. When an ideology becomes stronger than the desire for normality, something gets a little overturned, but it bounces back over the years.

And it varies from country to country.

For example, we in Hungary cannot relate to the BLM movement, and neither can people in the Far East, they see it as a cultural-historical ‘curiosity’.

Post-colonial literature is an equally important trend in many countries. Authors who are part of this trend are receiving awards one after the other, in France, United Kingdom, United States. We don’t understand that in Hungary, because we have never been a colonial empire. For them, it is a matter of conscience. Of course, we Hungarians can relate to the oppression, poverty and humiliation that say a Caribbean mother of four children talks about in a book, or to the story of someone who grew up in the apartheid of South Africa, because at home we may have had similar experiences. There are issues that we Hungarians do not understand, just as some of our issues are not understood abroad. Our literature is exciting for others if we manage to identify a unique issue in such a way that we can turn it into world literature.

The Petőfi Cultural Agency is also the publisher of The Continental Literary Magazine, a quarterly English-language publication. This is an all-American literary magazine with a strong focus on the literature of Central Europe with the aim of creating a platform for contemporary Hungarian and Central European fiction writers to stake out their place in the English-reading world and, in particular, the North American literary market. Representatives of the American and Eastern European intellectual and literary elite publish together in the magazine on a given, leading theme, such as Noam Chomsky and Thomas Zmeskal, Roxanne Gay and Krisztina Tóth, to give you a few examples. We are constantly receiving feedback, from Chicago, Philadelphia, New York and Boston to Vienna, Warsaw, Prague, Zagreb, Belgrade, Bucharest and Kiev, about how much of a gap this paper already fills. With the magazine a forum has been finally created that functions as an intellectual and artistic channel between two continents that are becoming increasingly separated from each other. If I can really believe in something during my work, it is these projects. It is worth putting all your energy and even a whole life into them.