Many feel strongly about whether the belief in God makes people selfish or altruistic. What is more interesting, however, is whether the subconscious belief that an omnipresent being is watching our decisions effects—or not—human behaviour. In a thought-provoking research paper published in 2007, Azim Shariff and Ara Norenzayan[1] investigate precisely this question. The study builds on earlier research that established that college students who were casually told that the ghost of a dead student was reported to be spotted in the private room where they were taking a test were significantly less likely to cheat than others who were not told this story. Similarly, when printed eyes were put on college ‘honesty boxes’ (used for collecting payments for drinks and snacks) the proportion of students who paid the correct sum (and not less) for their consumption increased. Subconsciously, the belief that we are being watched by an omniscient and omnipresent being affects our behaviour, making us act in a more prosocial way. Drawing on these earlier experiments, the 2007 study by Azim Shariff and Ara Norenzayan investigated whether God concepts also affect people’s behaviour.

In the cited study the two authors were primarily interested in the effects of God-related concepts on selfish and prosocial behaviour.

As a first step of the research, half of the research subjects were primed with sentences that included God-related concepts (e.g., prophet or God) while the other half of the participants were not. The first group was given five-word-long incorrect sentences (with God concepts) that they had to correct by removing one unnecessary word—thereby creating a four-word-long, correct sentence. The other group also had to correct sentences, but their sentences did not include any references to God. This priming method is widespread in social sciences—it is useful as participants tend not to connect it with the survey they need to take later, therefore, the effect these priming sentences have on the participants remains mostly subconscious. After finishing correcting the sentences, the participants were presented with ten one-dollar coins. They were told that were designated as the givers in the experiment, and they can take and keep as many of the coins they want. The bills that they take are theirs, they can decide how many they take, but they were also told that there is another subject, a receiver, who will receive the remaining coins. If they decide to take all coins, the receiver gets nothing. The participants were also told that their identity will not be disclosed to the next participant—so their reputation will not be damaged if they decide to take all or most of the coins.

Earlier studies had already established that

once people are told that the game was anonymous, they would leave little to no money on the table for the next participant.

While this study also found a selfish behaviour among those participants who were not primed with sentences about God, those participants who were asked to correct God-related sentences beforehand left much more money on the table for the next participant. Those who did not have God-related sentences before the experiment left, on average, $1.84 dollars on the table (52 per cent left $1 or less and no one left more than $5). Those who were given sentences about God concepts, on average left $4.22 (64 per cent left $5 or more). Even those participants who described themselves as atheists after the experiment was finished but were presented with God-related concepts before asking to take as much money as they wanted, decided to leave more money for the next person. Those atheists who were not presented with God concepts before asking to take a decision about the money took slightly more money (to a statistically non-significant extent) than those self-reported believers who were similarly not primed with God-related concepts.

In sum, it was not the self-reported belief in God that significantly changed people’s behaviour but whether they were primed or not with God concepts.

If they were primed, their tendency for prosocial behaviour increased.

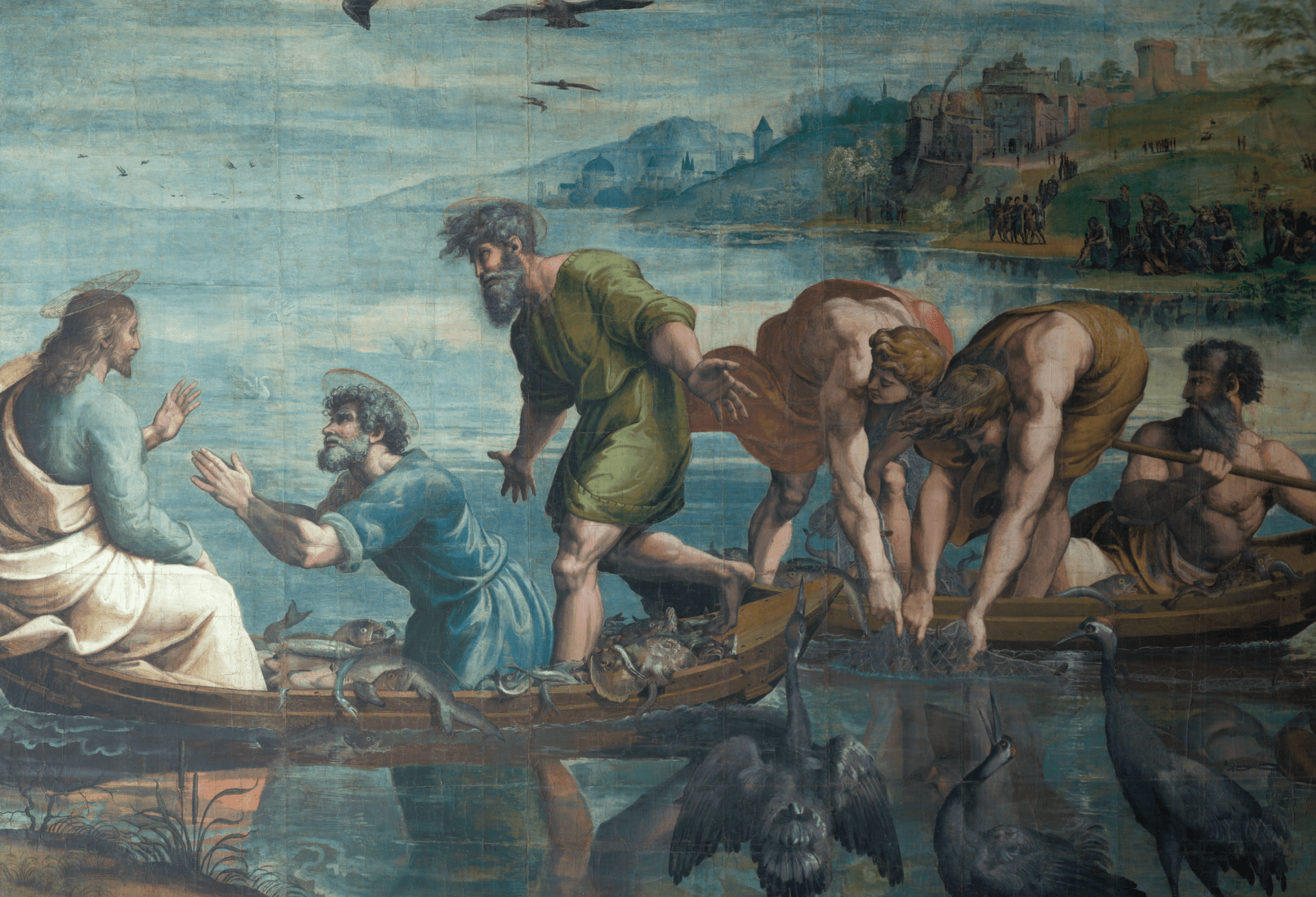

In other words, it was not the explicit belief in God, but the implicit religious prime that reduced selfishness and increased prosocial behaviour. The underlying question the paper addresses revolves around the puzzle of how genetically unrelated people end up cooperating and creating large-scale societies. Interestingly, the emergence of populous communities (i.e., genetically unrelated people living together) coincides with the spread of religious iconography. The answer this research paper offers for this puzzle is the following: as the belief in the existence of omniscient supranatural beings encourages prosocial behaviour, similarly, a shared faith helps unrelated people live in harmony in large communities.

[1] Azim F. Shariff and Ara Norenzayan, ’God Is Watching You: Priming God Concepts Increases Prosocial Behavior in an Anonymous Economic Game,’ Psychological Science, 18, p. 803.