In the course of history, the most radical changes in the image of Hungarians certainly took place one or two hundred years after the adoption of Christianity. Looking at the events from Hungary’s point of view, joining Latin Europe was a logical and, according to some historians, almost inevitable step in the decades following the Battle of Lechfeld in 955. At the same time, from the perspective of Europe, the Hungarians’ conversion to Christianity was by no means regarded as a break with their previous raiding culture—the Hungarian people was still considered suspicious, barbaric, and prone to paganism for a long time.

In addition to the unilateralism and partial injustice of the controversial political literature, the suspicious and critical wording includes, of course, the natural need for Westerners to distance themselves from their neighbours and the sense of superiority associated with them. The traditional ‘pagan Hungary’ image of the West underwent a slow metamorphosis. The process was also slowed down by the fact that the memory of the Hungarian destruction during their raids remained alive for a long time thanks to the monastery yearbooks, world history, and national history manuals.[1]

In its present form, The Song of the Nibelungs (Nibelungenlied in German), written around 1200, brought Hungary into the German literary public awareness in a special way: the image of a pacified Hun–Hungarian Empire that built relations with the West was made known by the German heroic tale in the German-speaking world. The most important result of the Hun–Hungarian tradition based on the identity of Huns and Hungarians is the embedding of Hungarian history into European, i.e. world history, and at the same time placing it in the Christian history of salvation.[2]

Surprisingly, Hungarian figures appear in the French chansons de geste (Old French for ‘song of heroic deeds’), from ‘The Song of Roland’ dating back to the beginnings of the 11th century to the artworks of the 12th and 13th centuries. In these chansons, the Hungarians appear as allies of the pagan Saracens, perhaps again as a late reflection of the tradition of their raids. From the 12th century onwards, however,

the country of the Hungarians was increasingly depicted as a Christian Kingdom from which it is a glory to come from.

Pannonia, for example, was given an honourable place in the origin-saga of the Franks, since Savaria (today Szombathely, Hungary), the birthplace of St Martin of Tours, had an incredible impact throughout Europe. On the earliest European maps, the country is represented as St Martin’s hometown, and so is it on the Hereford Mappa Mundi, the largest medieval map from around 1300.

Besides, the importance of dynastic relationships cannot be overemphasised. King Béla III (r. 1172–1196), the most outstanding Hungarian ruler of the 12th century, was at the forefront of the renewal of the Western orientation, as his first wife was Anne of Chatillon–Antioch, the daughter of the Prince of Antioch, and his second wife was French princess Margaret Capet. In addition, it was also in the 12th century that the first memories of famous Hungarian university classmates and professors appeared in academic education from Oxford to Paris.[3]

By the end of the 13th century, the House of Árpád became one of the dynasties that gave Europe the most blessed and holy kings, princes, and especially princesses. In this century alone, the veneration of a total of nine saintly princesses from the House of Árpád helped increase the good reputation of the dynasty and the country beyond our borders; one needs only think about the name of Blessed Elisabeth of Hungary and the pan-European veneration that quickly developed after her death (she died in 1231, and she was canonised already in 1235).

The rule of the Anjou and Luxembourg Dynasties (1307–1386 and 1387–1437) brought a basic change in terms of the development of the country’s image. Perhaps the most fundamental turn was that the kings of these dynasties already shaped the image of the country consciously, which later became truly spectacular during the reign of King Matthias of Hungary (1458–1490). To these rulers, it was evident that the glory of the dynasty belongs to the country as well. They realised that they can only form successful foreign policy alliances if there is unbroken faith and trust in the sovereignty and grandeur of the country. What had previously been achieved through occasional marriages was now ensured by the accession of foreign dynasties to the throne:

the country finally entered the bloodstream of European diplomatic and court life in the most natural way.

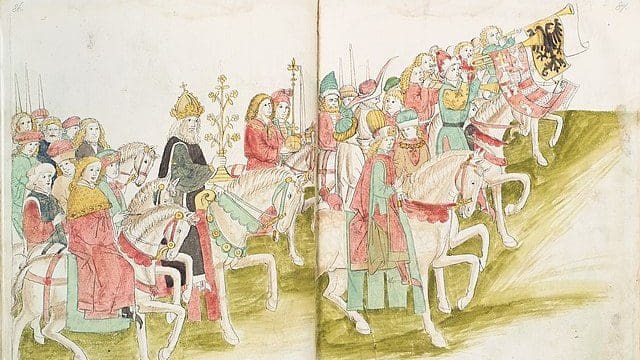

The previously unusual and only occasional forms of court representation became solidified during the reign of Louis the Great of Hungary. During the Árpád era, Hungarian rulers rarely left the territory of the country, although compared to previous rulers, the Anjous also travelled quite a lot abroad. Sigismund of Luxembourg, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Hungary, for example, found pleasure in diplomatic trips and negotiations from Rome to London, and sometimes he did not even set foot on native soil for years. Louis the Great’s personal participation in the Prussian and Lithuanian ‘crusades’, which were real European knightly meetings of the era, where, in addition to fighting, they also spent time with chess, hunting, and jousting, could also be related to his ambitions for the Polish throne.[4]

During Sigismund’s reign, all this was combined with the fact that when people talked about Hungary, they thought of the Emperor himself: Sigismund’s personality obscured his Kingdom along the Danube, even if the country’s prestige apparently benefited a lot from it. By Sigismund wearing the crown of several other countries (the imperial, the Italian, and the Czech) in addition to the Hungarian one, Hungary, including Buda and Bratislava, suddenly became an international centre, too. A significant difference between Sigismund and Louis the Great is that the former’s representation abroad was much more secular than that of the latter: the highlight of Sigismund’s trip to Paris, which aroused a great deal of interest, was his visit to the French Parliament and his judgment there. After his arrival, he often held a ball for the ladies of a town and gave them gifts. Of course, the emperor himself also felt the difference between the Hungarian reality and the big European centres of the time, and therefore he never ceased to invite various foreign artisans to his country. He was extremely interested in attractions and technical innovations, so it is no surprise that he was offered several manuscripts on such and similar subjects from Italy to Germany. In 1414, for example, in Nuremberg, he inspected the first German paper mill, and representatives of German merchant houses appeared in his circles from the first years of his reign as well.

It is therefore hardly surprising that the Emperor who organised and directed the Council of Constance, who successfully eradicated the schism, who was at war with the Hussites for years, and who ended the crisis diplomatically, was the one among all the Hungarian rulers mentioned and depicted the most abroad. In any case,

the first realistic portrait of a Hungarian king depicts Sigismund.[5]

Sigismund’s diplomatic brilliancy was also manifested in the organisation of the Battle of Nicopolis and the last great Crusade in 1396, with which, despite the catastrophic failure, he managed to get away suffering only a minimal loss of international prestige. By all means, he achieved that the whole world was talking about the ‘Hungarian campaign’. He also generously accepted half of the huge ransom demanded for the Duke of Burgundy, who was captured by the Ottomans in the battle, without actually paying anything—and even with this he earned recognition.

All of Sigismund’s gestures were for the public. He achieved everything that King Matthias later wanted to achieve, even if he did not write historical works to glorify himself. Among the members of the equestrian order he founded, the Order of the Dragon, there were quite a few foreigners, let us just mention the kings of Denmark, Aragon, Poland, and England. Despite a large number of donations, it seems that the recipients considered the badge of the order a serious honour, and they did not fail to depict it on their clothing, personal items, and tombstones either.[6]

Based on foreign comments about Hungary, the country actually received a more positive judgement than its people did. The Kingdom of Hungary was huge—even without Dalmatia it was one of the largest countries in Europe, and its fertility and richness in natural resources lived up to its reputation. However, in a state of constant war, it cannot be considered an exaggeration that the Hungarians were valiant, fond of fighting, susceptible to violence, and had good horses. The Hungarians’ determination to fight the Ottomans was hard to doubt, even if political party struggles gave some basis to foreign criticism. At the same time, references to simplified lifestyle and crude manners were not baseless either. Even the not-so-farsighted Western travellers could notice that compared to Hungarians, the people of Vienna were much better dressed, or that the Hungarian roads were rather rough—behind the various representations and the spectacular campaigns, the reality could not always remain hidden.

[1] Enikő Csukovits, Hungary and the Hungarians: Western Europe’s View in the Middle Ages, Rome, 2018, pp. 17–25.

[2] Tünde Radek, Das Ungarnbild in der deutschsprachigen Historiographie des Mittelalters, Frankfurt am Main, 2008.

[3] Sándor Csernus, ‘La Hongrie et les Hongrois dans la littérature chevaleresque Française du Moyen Âge’, in Noël Coulet, Jean-Michel Matz (eds.), La noblesse dans les territoires angevins, Rome, 2000, pp. 717–735.

[4] Sándor Csernus, ‘From the Arsenal of Sigismund’s Diplomacy: Universalism versus Sovereignty’, in Attila Bárány (ed.), Das Konzil von Konstanz und Ungarn, Debrecen, 2016, pp. 9–32.

[5] Vilmos Tátrai, ‘Darstellung Sigismunds von Luxemburg in der italienischen Kunst seiner Zeit‘, in Imre Takács (ed.), Sigismundus Rex et Imperator. Kunst und Kultur zur Zeit Sigismunds von Luxemburg, Mainz, 2006, pp. 143–152.

[6] Pál Lővei, ‘Monarchical orders in medieval Hungary: the Orders of Saint George and the Dragon’, in Gianina-Diana Legar, Levente Szőcs (eds.), The unfinished Middle Ages, Cluj-Napoca, 2022, pp. 95–113.

Related articles: