This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 1 of the print edition.

Hundreds of articles have been written about Whittaker Chambers and his improbable but successful efforts to bring the communist spy Alger Hiss to justice. But few—none that I have read—have related the most important piece of the puzzle: his life-changing, divine encounter, during which Chambers said he clearly received a twelve-word message from God.1

People claiming to have heard directly from God are often regarded as suspect. So, it is important for readers to come to their own conclusions. Personally, I believe Chambers’s encounter with God was genuine. The resulting, seemingly miraculous events and the overall positive impact on the world have confirmed my opinion. But you decide.

My journey to the twelve words began with me on a treadmill, listening to the transformative ‘Evil Empire Speech’ by Ronald Reagan. It was a voyage of discovery that ‘changed my worldview, my philosophical perceptions, and, without exaggeration, my life’ (I use this quote by Robert Novak because it also describes my experience upon reading Witness, the autobiography of Whittaker Chambers).2

Near the end of his speech, Reagan used a powerful quote from a person about whom I knew nothing. He said: ‘While America’s military strength is important, let me add here that I’ve always maintained that the struggle now going on for the world will never be decided by bombs or rockets, by armies or military might. The real crisis we face today is a spiritual one; at root, it is a test of moral will and faith. Whittaker Chambers, the man whose own religious conversion made him a witness to one of the terrible traumas of our time, the Hiss-Chambers case, wrote that the crisis of the Western world exists to the degree in which the West is indifferent to God, the degree to which it collaborates in communism’s attempt to make man stand alone without God. And then he said, for Marxism–Leninism is actually the second-oldest faith, first proclaimed in the Garden of Eden with the words of temptation, “Ye shall be as gods.” The Western world can answer this challenge, he wrote, “but only provided that its faith in God and the freedom He enjoins is as great as communism’s faith in Man.”’3

The transcendent power of Chambers’s quote and the importance attributed to it by Reagan stimulated my curiosity. Who was Whittaker Chambers? I quickly found his autobiography, Witness, and began reading. I was captivated and wondered why I had never learned his story. It was as if I was hearing about the Pilgrims or the signing of the Declaration of Independence for the first time. My intense interest was noted by my son, Peter, who, one day, came into the living room where I was absorbed in the book and said, ‘you must really like this book’. He was right.

This article will present the reader with a basic understanding of the tragic but triumphant life of Whittaker Chambers, the man whose dramatic, twelve-word encounter with God and subsequent heroic exploits became the inspiration for a new generation of conservatives, like Ronald Reagan. The twelve words and Chambers’s story are becoming increasingly relevant today, as humanistic forces are once again enticing global culture to organize itself based on the ideas of mortal men, ‘ye shall be as gods’.

Whittaker Chambers was sensitive and intelligent but grew up in an utterly dysfunctional home. The pain was greatly intensified by the suicide of his brother, Richard, whom he deeply loved. This event was the tipping point, causing him to turn to communism, which offered a way to ‘fix’ the world and the pains that Chambers had seen as inescapable.

In 1921, as a student at Columbia College, he sought out groups that were exploring left-leaning ideologies, including communism. But there was a difference between him and his fellow ‘travellers’: he was serious. Eventually, he asked to be connected with a real Communist, which, in 1925, led to him becoming actively involved in the Communist Party. At first, he was active in legal, non-secret activities including writing for the prominent propaganda publication, The Daily Worker. However, in 1932, he became part of an illegal, secret spy network (cell) called the ‘apparatus’ and in 1934 he was introduced to Alger Hiss. Over the ensuing years, he and his wife, Esther, became close friends with Alger and his wife Priscilla. Eventually, Hiss rose to becoming an assistant to the Assistant Secretary of State, Francis Sayre, where he had access to confidential government information. In 1937, as part of the espionage apparatus, Hiss began covertly removing State Department documents and delivering them to Chambers. Chambers would make photographs of the documents and return the originals to Hiss, who would then put them back in the offices of the State Department. Fortunately, Chambers copied and saved some of these documents, evidence which would be pivotal in the conviction of Hiss. Chambers worked in the shadows for several years, with Hiss and others, in covert, treasonous espionage against the United States during the Roosevelt administration. He met and/or worked with several prominent communist underground ‘functionaries’, who were part of other apparatus cells. He would name twenty-one of these as part of his later testimony.4

‘The real crisis we face today is a spiritual one; at root, it is a test of moral will and faith’

Over time, Chambers’s idealism eroded as he heard rumours of Stalin using devious means to accomplish his agenda, including purges of some of Chambers’s colleagues and even mass murder. Even more influential were divine moments that made him reflect. One such incidence, which Reagan often referred to, was Chambers’s experience feeding his baby daughter. He said of it, ‘My eye came to rest on the delicate convolutions of her ear—those intricate perfect ears. The thought passed through my mind: “No, those ears were not created by any chance coming together of atoms in nature (the Communist view). They could have been created only by immense design.”… I did not then know that, at that moment, the finger of God was first laid upon my forehead.’5

Then, in 1938, came his life-changing encounter with God. Under intense pressure and self-doubt, Chambers asked himself whether he could make a Lazarus-like ‘impossible return’ to freedom from communism. He contemplated suicide. He was at his apartment in Baltimore when it happened: ‘As I stepped down into the dark hall, I found myself stopped, not by a constraint, but by a hush of my whole being. In this organic hush, a voice said with perfect distinctness, “If you will fight for freedom all will be well with you.”’ Upon hearing the words, he was a changed person. He wrote, ‘On one side of that moment were nearly forty years of human waste on all the paths and goat paths of 20th century error and action. On the other side was humility and liberation, the sense that the strength would be given me to do whatever I must do, go wherever I must go… It was the strength that carried me out of the communist party, that carried me back into the life of men. It was the strength that carried me at last through the ordeal of the Hiss case. It never left me because I no longer groped for God; I felt God. The experience was absolute.’6

Again, few articles about the Chambers story include this event; yet it is the most important piece of the puzzle. Without it, it is doubtful whether Chambers would have been able to continue, for, as he suspected, the path ahead led to great hardship for him and his family. Later he wrote, ‘I am a man who reluctantly, grudgingly, step by step is destroying himself that this country and the faith by which it lives may continue to exist’.7 Later that year, Chambers tried, passionately but unsuccessfully, to persuade his good friend, Alger Hiss, to leave the Communist Party.8

Chambers was now confronted with two ominous challenges: exiting the party and informing the US government of his espionage and the impending danger. Chambers and his faithful wife, Esther, planned their—to say the least—challenging exit from the party and disappearance from their residence in Baltimore over the course of several months. The danger was real since there were always eyes watching to ensure the faithful remained faithful. Then, one day, they made their move and left without a trace. When he entered the apartment one last time to retrieve a forgotten item, he heard the eerie ring of the phone in an empty apartment, most likely a comrade wondering where he was. He let it ring. This was it: he was leaving the Communist Party and risking the lives of himself and his family. As he said to his wife, ‘I know that I am leaving the winning side for the losing side, but it is better to die on the losing side than to live under communism’.9 They drove to Florida and hid for a year.

The next task was confession. He had to make good on what he told his friend who, in 1937, urged him to break with the Communist Party: ‘You know that the day I walk out of the Communist Party, I walk into a police station.’ So, in September of 1939, a meeting was arranged for Chambers with Adolf Berle, the Assistant Secretary of State under Franklin Roosevelt. Chambers’ confession included specific names, including Alger Hiss. Remarkably, nothing happened. It was not until nine years later, when more evidence was collected from another communist defector, Elizabeth Bently, that the authorities came calling on Chambers.10

After their year in hiding, Chambers moved his family back to a small farm in Maryland. More trouble followed. One day, Esther showed him her purse that contained less than fifty cents. He needed a real job. Fortunately, that very day, he received a letter from a dear friend, Robert Cantwell, urging him to apply immediately for rare openings at the prestigious Time magazine. Chambers borrowed ten dollars from some kind neighbours, hastily travelled to New York and got the job. Over the ensuing nine years, his brilliance and remarkable writing ability helped him rise to the position of senior editor, where he authored stinging articles about the Soviet Union. As a result, he was vilified by many who believed the Soviet Union was a viable and successful alternative to free-market capitalism.11

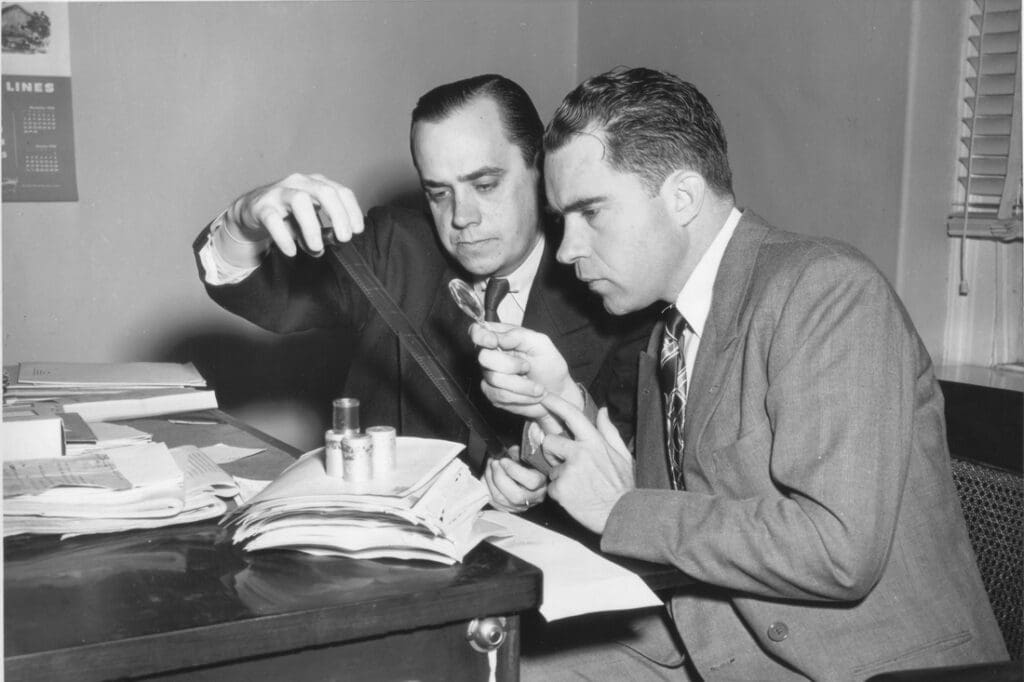

Finally, nine years after his confession to Adolf Berle, Chambers was subpoenaed for testimony by the House Un-American Activities Committee. The committee included a determined young Congressman, and future president, Richard Nixon.

Chambers began his testimony on 3 August 1948, and just one day later the news broke that a confessed former Communist had accused the highly respected Alger Hiss of being a Communist. Hiss adamantly denied the charge. For eighteen months, America became enveloped in a quest to find out who was lying, Chambers or Hiss? The public was transfixed. Though Chambers’s accusation was substantial, a much greater charge was soon to come.12

Extensive and gruelling depositions began for Chambers and Hiss, who had assembled a strong defence team. Under private depositions, Chambers was protected against libel. So, Hiss’s defence team challenged him to make his accusation, of Hiss being a Communist, in public. After much indecision and with great trepidation, Chambers decided to accept their challenge. So, on 27 August 1948, on the radio programme Meet the Press, Chambers was pointedly asked: ‘Are you willing to repeat your charge that Alger Hiss was a Communist? He answered, ‘Alger Hiss was a Communist and may still be one.’ Hiss’s team hesitated, but did file their libel lawsuit, and the pot boiled higher and hotter; yet more was to come.13

Chambers, though he had publicly accused Hiss of being a Communist, was still withholding critical information. He was actually protecting Hiss because they had been such good friends. But, finally, under intense pressure from Nixon and Robert Stripling, the chief investigator for HUAC, Chambers revealed that Hiss was not only a Communist, but had been actively involved with him in espionage.14

Immediately, the matter escalated to a criminal investigation. The Justice Department was notified, and evidence was demanded. Chambers went back to his wife’s nephew’s home, where he had hidden the copies of stolen state department documents and, thankfully, the evidence was still there, though dusty and aged. Chambers brought these copies into the deposition room and laid them on the table. A whole new level of drama ensued. Could Hiss actually be guilty, not only of being a Communist, but of espionage?15

The Justice Department was now faced with the daunting challenge of proving in court that Alger Hiss had lied under oath about his dealings with Chambers, which in effect proved he was indeed involved with Chambers in espionage. Since the statute of limitations had passed Hiss was not liable for the actual crime of espionage. Two sensational trials followed, with Americans glued to the news. Evidence included a typewriter, copies of documents passed to the Soviets, microfilm, personal testimonies, and even a bird. The most famous evidence was the microfilm which Chambers had hidden in a hollowed-out pumpkin on his farm. These became known as ‘The Pumpkin Papers’. (As an aside, every year in Washington, DC and appropriately during the Halloween holiday, a group of Chambers’ supporters, ‘The Pumpkin Papers Irregulars’ meet to commemorate the heroic contributions of Whittaker Chambers.)16 Finally, in the second trial, Hiss was convicted and went to jail.

It should be noted that, during this time, Chambers not only contemplated but attempted suicide, using a cyanide compound. He bought the ingredients, went to his mother’s home, started the gas reaction, and went to sleep. He woke up sick, but alive. He termed it ‘self-execution’, since he felt the world would be better off with him dead.17 Among many other highly emotional dilemmas, he remained conflicted between his obligation to tell the truth and loyalty to Hiss. Unlike Senator Joe McCarthy, who became famous for attacking alleged Communists, Chambers had true sympathy for those he was testifying against. He said: ‘The story has spread that in testifying against Mr Hiss I am working out some old grudge, or motives of revenge or hatred. I do not hate Mr Hiss. We were close friends, but we are caught in a tragedy of history. Mr Hiss represents the concealed enemy against which we are all fighting, and I am fighting. I have testified against him with remorse and pity, but in a moment of history in which this Nation now stands, so help me God, I could not do otherwise.’ After two trials, Alger Hiss went to jail for lying under oath. They could not charge him with espionage since the crime had occurred so far in the past; the statute of limitations was in effect.18

The sensational trial was over, Hiss was convicted, and the liberal establishment was in trouble. One of their darlings was in jail and, more importantly, conservatives had found a brilliant, articulate, and courageous hero. But what was Chambers to do now? Because of the controversy, he had left Time magazine and was considered toxic by other publications. Many still thought Hiss to be innocent. So, with plenty of time on his hands, he retreated to his farm and proceeded to write, as George Will said, ‘One of the dozen or so indispensable books of the century’.19 It was an immediate best-seller and became a rallying point for many conservative leaders, including Ronald Reagan, who credited the book as the inspiration behind his conversion from a New Deal Democrat to a conservative Republican.20

Chambers’s autobiography combined three critical elements: God, freedom, and the importance of America. About America, once his mortal enemy, he wrote that he ‘meant to raise at least a hand to help save what was left of human freedom, and, specifically, that nation on which the fate of all else hinged.’21

In the aftermath, William Buckley asked Chambers to write for his new publication, National Review. Buckley proposed that the publication would, like the diaries of Anne Frank, remind the world that the concept of liberty was worth saving. He believed this argument finally convinced Chambers to begin writing for the publication.22 Sadly, Joe McCarthy also came calling and used the Hiss trial as ammunition for his large-scale and often indiscriminate attacks on government officials suspected of communist activities. Chambers was prophetic when he said of McCarthy, ‘It is no exaggeration to say that we live in terror that Senator McCarthy will one day make some irreparable blunder which will play directly into the hands of our common enemy and discredit the whole anti-Communist effort for a long while to come.’23 That was indeed what happened.

‘Humanistic forces are once again enticing global culture to organize itself based on the ideas of mortal men, “ye shall be as gods”’

Two important current issues now awaited Chambers’ opinion: The New Deal and Ayn Rand’s version of freedom. Roosevelt’s New Deal was beloved by many; however, it was renounced by Chambers, who said, ‘All the New Dealers I had known were Communists or near-Communists. None of them took the New Deal seriously as an end in itself. They regarded it as an instrument for gaining their own revolutionary ends…’24

Chambers also addressed Ayn Rand’s concept of freedom. Her books Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged were considered by many on the right as compelling arguments to combat liberal thought. Her views became known as ‘libertarianism’. Chambers rightly and soundly denounced her ideas in his article ‘Big Sister Is Watching You’. He correctly pointed out that she did not include God in her concept of freedom. As he wrote, ‘Like any consistent materialism, this one begins by rejecting God, religion, original sin, etc., etc. … Thus, Randian Man, like Marxian Man, is made the center of a godless world.’25

As conservatives, we must vigorously defend the divine nature of freedom. As Chambers expressed: ‘Freedom is a need of the soul, and nothing else. It is in striving toward God that the soul strives continually after a condition of freedom. God alone is the inciter and guarantor of freedom. He is the only guarantor. External freedom is only an aspect of interior freedom. Political freedom, as the Western world has known it, is only a political reading of the Bible. Faith in God and freedom are indivisible. Without freedom the soul dies. Without the soul there is no justification for freedom.’26 Being a dedicated former Communist, a deeply thoughtful, orthodox Christian, and an exceptional journalist put Chambers in a powerful position from which to address foundational aspects of freedom.

On a sad note, no major movie or TV series about Witness or the Hiss–Chambers trial has ever been produced. The story of Whittaker Chambers is filled with aspects that would make for a successful ‘big screen’ movie. There are even major actors who have indicated an interest in playing the role of Chambers. However, for various reasons, no major movie has been produced, nor is one currently under consideration. Thankfully, there are some productions on YouTube including John Beressford’s excellent 38-part lecture series called ‘A Pumpkin Patch, a Typewriter and a Pumpkin’.

I believe, one day, a feature film will emerge to spread the twelve word message of freedom to the next generation. In the meantime, I have created a website for those wanting to learn more or share their thoughts about Whittaker Chambers and his fight for freedom. It is appropriately named www.ifyouwillfightforfreedom.com.

Twelve words gave one man the courage to risk his life for freedom and America, the country that embodied freedom. It seems fitting to end with those words: ‘If you will fight for freedom, all will be well with you.’

NOTES

1 Whittaker Chambers, Witness (New York: Regnery History, 1952; Reprint 1969), 1, 56–57. Author’s note: The reference contributions for this article were prepared by Meredith Smith.

2 Chambers, Witness, xviii.

3 Ronald Reagan, ‘Evil Empire Speech’, Voices of Democracy, https://voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu/reagan-evil-empire-speech-text/, accessed 23 December 2022.

4 Richard Reinsch, YouTube Video, Whittaker Chambers: The Spirit of a Revolutionary, 24 April 2016, Heritage Foundation book event, 8/18/2010.

5 Chambers, Witness, xlv.

6 Chambers, Witness, 56–57.

7 Chambers, Witness, 628.

8 Chambers, Witness, 45.

9 Chambers, Witness, 469.

10 Chambers, Witness, 39, 485.

11 Chambers, Witness, 56–57.

12 Douglas Linder, ‘The Trials of Alger Hiss, a Chronology’, Famous Trials, University of Missouri–Kansas School of Law, www.famous-trials.com/algerhiss/641-chronology, accessed 23 December 2022.

13 Chambers, Witness, 623–625.

14 Chambers, Witness, 639–644.

15 Chambers, Witness, 647–650, 661.

16 Chambers, Witness, 503–506, 683–684.

17 Chambers, Witness, 682–684.

18 Chambers, Witness, 614, 701–702.

19 George Will, Cover Endorsement, Witness (New York: Regnery History, 1952; Reprint 1969).

20 Linder, ‘The Alger Hiss Trials’.

21 Linder, ‘The Alger Hiss Trials’.

22 William Buckley, ‘The Party at the Plaza’, National Review, 1/1 (1986), www.nationalreview.com/1986/01/party-plaza-william-f-buckley-jr/, accessed 23 December 2022; also see Chambers, Witness, xii.

23 Letter by Whittaker Chambers to Henry Regnery, 14 January 1954.

24 Chambers, Witness, 407.

25 Whittaker Chambers, ‘Big Sister Is Watching You’, National Review, 28/12 (1957), www.nationalreview.com/2005/01/big-sister-watching-you-whittaker- chambers/, accessed 23 December 2022.

26 Chambers, Witness, xlv.

Related articles: