Jabotinsky was an old-fashioned nineteenth-century national liberal and a committed democrat, but it is still a matter of debate whether the same can be said of his supporters. The Zionist writer described his early worldview as ‘liberal anarchy’ in which ‘every individual is [worth as much as] a king’. The free market, freedom of the press, equality for women and respect for minority rights were fundamental tenets of his thinking. But there is good reason why there is an intense historiographical debate concerning Jabotinsky’s views.

‘What better explains the atrocities committed: coercion or the individual’s capacity or inclination for cruelty? Perhaps both, but to varying proportions.’ Author and historian László Borhi points out in his 2022 book The Strategies of Survival that, in his research, it was not always possible to draw a clear line between the different roles. ‘Several were convicted of collaborating with the Nazis and collaborating in atrocities, while other witnesses claimed that the person in question saved their lives’.

There is a group of people who will demand photos of Jewish victims and then, when they get them, rejoice in the fact of the killings. Meanwhile, one cannot forget that there is obviously a benign, uninformed majority that can be persuaded by either side, and Israel must not give up the possibility of persuasion.

Moscow has failed to condemn the 7 October Hamas attack as terrorism, and Putin has likened the Gaza blockade by Israel to the siege of Leningrad by Nazi Germany, effectively poisoning the previously amicable Russia–Israel relations.

Although a defining part of Netanyahu’s image is that of ‘Mr Security’, and he has even been nicknamed ‘King Bibi’, the spectacular fiasco of a 1997 Mossad operation he had ordered also earned him the epithet ‘Israel’s serial bungler’.

Can Netanyahu survive as prime minister in the wake of the Hamas attack? Are Jews really safer in Israel today than in the Diaspora? Hard questions that need to be asked.

The anti-Zionist Orthodox Jews demonstrating in New York are therefore not necessarily a curiosity. They are representatives of an old and historically legitimate school of thought, albeit completely marginalized and despised in their own religious milieu as well. Their presence simply demonstrates that Judaism is diverse, that there are all kinds of trends within it, and that it is not possible to treat this community as a single monolith.

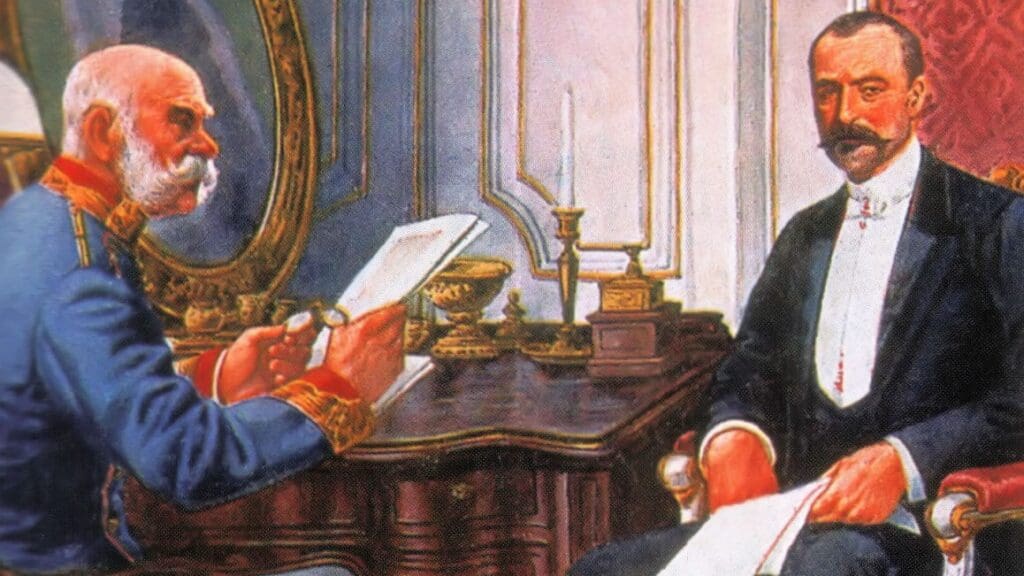

On 15 October 1944, Horthy made an unsuccessful attempt to exit the Second World War. The operation failed due to a number of reasons: the resistance of some officers of the Royal Hungarian Army, organisational mistakes and pre-emptive actions by the Nazi secret service. Horthy was soon forced to resign.

‘These recent bloody events—and the videos of Arab crowds celebrating them, not just in Gaza, but in Europe too—show perfectly what a significant part of the Muslim Arab world thinks about the issue. The problem is not that Israel is ‘running the world’s largest concentration camp’ in Gaza (a distasteful and debatable claim in the first place, but let’s not go into that now). This conflict existed before the majority of people alive today were born.’

The work of Gombos, both as a writer and a literary historian, is still undeservedly understudied. As one of his admirers quite aptly wrote of him: ‘His place in the hierarchy of “populist” thinkers and writers is not in the second, but in the first rank, in the company of those whose intellectual and creative achievements can be considered particularly valuable and significant.’

The extreme judgements about Begin have often been motivated by political ambitions and therefore do not help historical clarity. 110 years after his birth it is time to appreciate his values while not turning a blind eye to his flaws either.

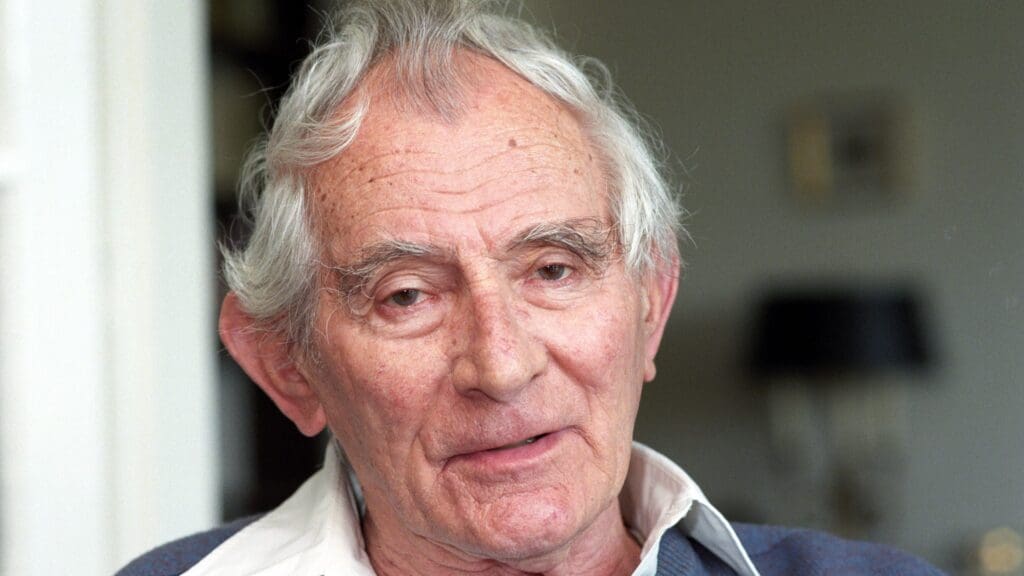

Faludy, one of the greatest Hungarian poets and literary translators of the 20th century, never really found his place in any system; he sooner or later became a nuisance to everyone, and even if sometimes made compromises, always did so provocatively, originally and with talent.

When it became evident that the War of Independence was lost, Prime Minister Bertalan Szemere and his men buried the Holy Crown and the other coronation regalia near Orsova (Orșova) in August 1849, to prevent the Habsburgs from laying their hands on them. The crown jewels were only found in September 1853.

Géza Szőcs, a Transylvanian Hungarian poet, writer, public intellectual and politician, who resisted the oppression of the Romanian communist dictatorship, was born exactly 70 years ago today.

National anniversaries, especially 15 March, were regularly celebrated in the Dohány Street synagogue. Mourning services were also held on the occasion of the passing of great Hungarian statesmen. In addition to the regular services, the synagogue also hosted a number of special events. On 20 December 1860, a ‘Jewish–Hungarian brotherhood’ ceremony was held, attended by statesmen, scholars, writers and artists, and for the first time, the Szózat was sung in a Jewish synagogue. On 8 April 1861, a memorial service was held for István Széchenyi, and in 1894 for Lajos Kossuth.

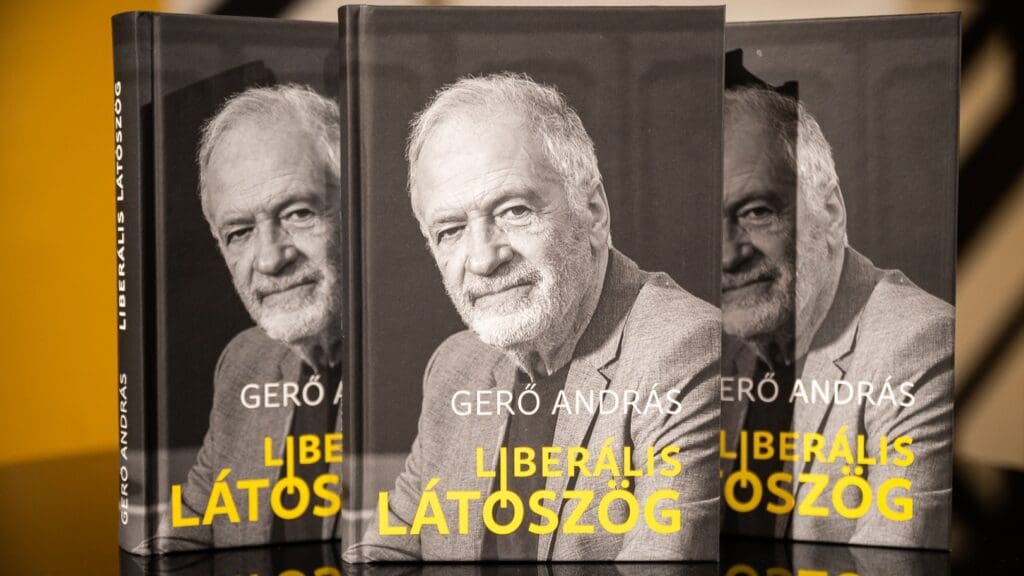

Gerő sees classical liberalism as the idea of a constitutionally limited state and individual liberties, based on natural law. According to Gerő, classical liberalism professes the principles of government being accountable to parliament, the separation of powers, and popular rule by suffrage. In that sense, Gerő sees the reform era of Hungary (1825–1848) as the beginning of the equality of civil rights.

‘Gárdonyi was a unique personality, a distinctive Hungarian writer, in both his good qualities and his faults. He cannot be branded or put in a box. He must be seen in the light of what he created, with his insightful criticisms taken to heart, and his failures appropriately assessed.’

‘One might conclude that only rogue states wage war without declaring it, yet the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the prolonged military involvements in Afghanistan and Iraq were not preceded by a declaration of war issued by the United States Congress either.’

Why did those who had the power to do so not pull in the reins? How could the civilised European populaces celebrate the war? Why did they not choose the path of peace, progress, and constructiveness? On the 109th anniversary of the start of the First World War, and in the shadow of the war of our time, these are the questions historians must answer.

A short story of a group of desperate young Hungarians who in 1956, disillusioned with socialism, overpowered the passengers and the secret agent on a plane, successfully flew it to Germany, and the leaders of whom eventually became members of the US military.

Jewish-Hungarian MP from the Horthy era Béla Fábián was held as a POW in Russia in World War i, and was taken to a concentration camp in World War II. He became an avid critic of the Hungarian Communist Party while living in exile in the 20th century, for which the Kádár regime subjected him to a smear campaign, claiming that he actually served as a ‘kapo’, a prisoner-turned-guard in his camp. Here’s the story of the extraordinary life of a special man.

‘Szekfű described “capitalism” as “having grown in size over time, becoming a more and more fearsome monster, creating factories and cramming hundreds of thousands and millions of people into the unhealthy, immoral air of smoky cities. And the longer the unrestricted freedom proclaimed by liberalism lasts, the more freely the capitalist big business devours the little ones, the more freely it exploits the economic weaklings, especially the workers.” Szekfű’s book Three Generations, in which he also called for extensive worker protection and the regulation of industrialists by law, bears a striking resemblance to the basic tenets of socialism.’

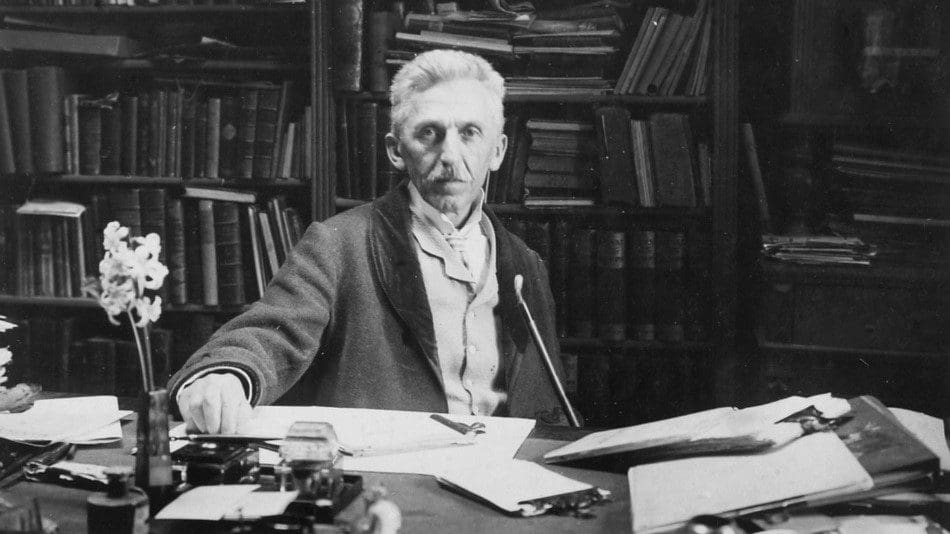

In 1869, the new statistical office of the capital was created, headed by Kőrösy. A few years later, he started to teach statistics in Budapest, the very first person to do so in Hungary. In 1896, he became a doctor of the University of Kolozsvár (today, Cluj in Romania), and was awarded nobility and the title of szántói, as well as the right to spell his name with a ‘y’ (indicating noble ancestry). The family never converted to Christianity, though, and the Kőrösy coat of arms included two stars of David.

Beside serving as chief engineer during the construction of the Chain Bridge, Clark was also involved in the building of the tunnel under the Buda Castle, and was also a board member of the company building the first Hungarian steamer ship. Other projects that Clark supervised include the construction of the mental health institute of Lipótmező and the roofs of the Dohány street synagogue.

The presence of Soviet troops in Hungary was of course illegal. The Paris Peace Treaty of 1947, which ended the war, required them to be withdrawn from our country, and although the treaty allowed for the necessary number of soldiers to remain here to ‘maintain the lines of supply’, there were obviously many more than that. The ‘legalisation’ of the presence of the Soviet forces that crushed the 1956 revolution was carried out by the new, collaborationist Kádár government in 1957.

Reuven Hecht was a right-wing Zionist who worked with the revisionist movement’s founding father, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, and after the founding of the state, became an Israeli entrepreneur and right-wing politician. Today, a museum and park in the Jewish state bear his name. After trying to help the Horthy family obtain a Swiss visa, he remained in correspondence with them until his death in 1993.

The book’s greatest value can undoubtedly be found in its historiographical sections, which present the historical assessment of the Soviet Republic and the Horthy system. It is in these that the author utilises the largest literary material and provides the widest overview.

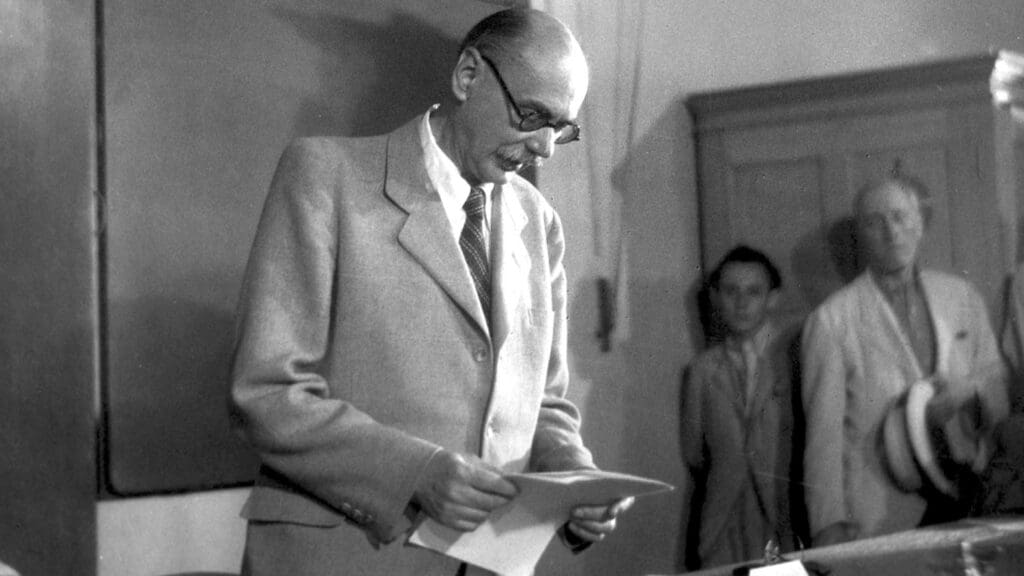

Nagy was a highly controversial figure in Hungarian history, whose assessment is still a source of intense debates…He did stand up for the Hungarian Revolution in 1956—for debatable reasons—; but to portray him as a convinced democrat, or a hero of Hungarian popular representation and individual freedom would be a serious distortion. His legacy must be treated in its proper place: his merits must not be denied, but his sins must not be forgotten.

As reported by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), the Action and Protection Foundation, through its Brussels Institute, recorded 37 antisemitic acts in Hungary in 2021. By comparison, in France there were 589 recorded antisemitic actions and threats in the 2021. In the same year, in Germany 3027 incidents were recorded. In addition, as highlighted by FRA, when looking at 2013–2021, the overall trend in Hungary was that the number of recorded antisemitic incidents was decreasing.

Losing the World War and the experience of the Treaty of Trianon triggered a discourse in Hungarian public life that was not without precedent, but had never been so vehement before. Perhaps the opinion of many was reflected by the renowned writer Ferenc Herczeg, who declared that ‘Europe, free press, liberalism—all these are slogans that have deceived us.’

Hungarian Conservative is a quarterly magazine on contemporary political, philosophical and cultural issues from a conservative perspective.