As reported by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), the Action and Protection Foundation, through its Brussels Institute, recorded 37 antisemitic acts in Hungary in 2021. By comparison, in France there were 589 recorded antisemitic actions and threats in the 2021. In the same year, in Germany 3027 incidents were recorded. In addition, as highlighted by FRA, when looking at 2013–2021, the overall trend in Hungary was that the number of recorded antisemitic incidents was decreasing.

Losing the World War and the experience of the Treaty of Trianon triggered a discourse in Hungarian public life that was not without precedent, but had never been so vehement before. Perhaps the opinion of many was reflected by the renowned writer Ferenc Herczeg, who declared that ‘Europe, free press, liberalism—all these are slogans that have deceived us.’

Bartha highlights that it is a painful phenomenon that the non-Communist Hungarian resisters ‘have been relegated to the no-man’s land in terms of memory politics in the 21st century.’ Hopefully, in the future, more attention will be devoted to the anti-Nazism not only of Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky or Lieutenant General János Kiss, but also that of István Lendvai, István Zadravecz or even Gyula Kornis.

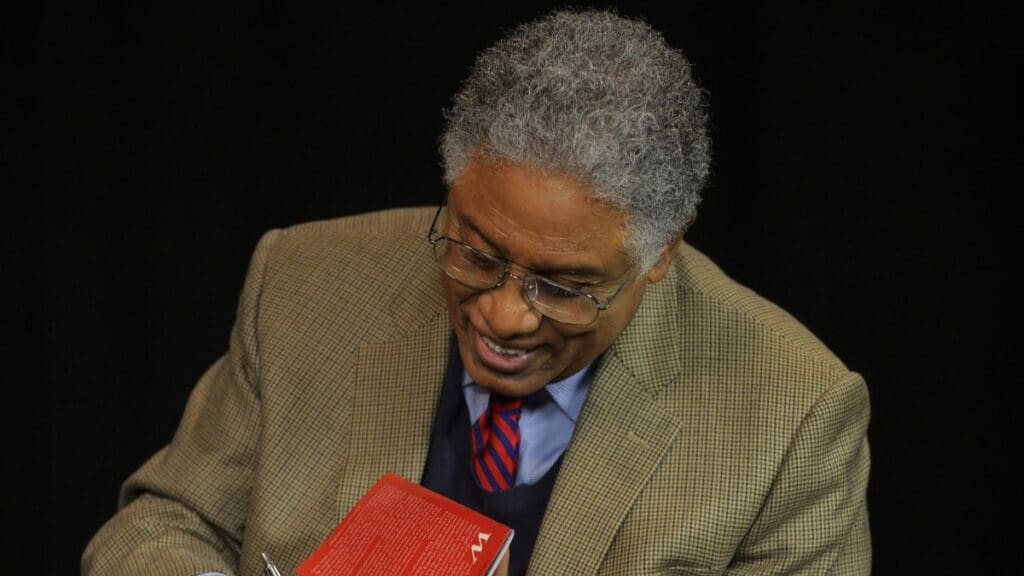

Sowell begins his book by stating that there are many explanations for inequalities, which broadly fall into two extreme categories: some believe that inequality is rooted in descent, in genetics, while others believe that the less well-off are exploited by the rich. Sowell believes in neither as an exclusive explanatory factor. Instead, he holds that success depends on certain preconditions, where even small differences can lead to big differences in outcomes.

Today, confirmed anti-Semites may be the ‘great friends of the Jews’, but members and sympathisers of the government that proclaims ‘zero tolerance’ regarding anti-Semitism at all international and domestic fora, and which unequivocally stands by and up for Israel, can be labelled as the ‘new anti-Semites’. Israelis cannot invoke the Holocaust as an argument of her legitimacy and a historical event of her people, because the ‘new Jews’ are Palestinians and migrants. Now ‘Nazi’ apparently denotes a right-wing Jew in some circles, while Nazis seem to be the ‘guests of honour’ at seder tables.

In March 1945, the chief notary of the Simontornya district in Tolna County reported that 60 per cent of the female population of the village of Nagyszékely was infected with venereal disease, and that girls aged 12–13 were among the victims of rape.

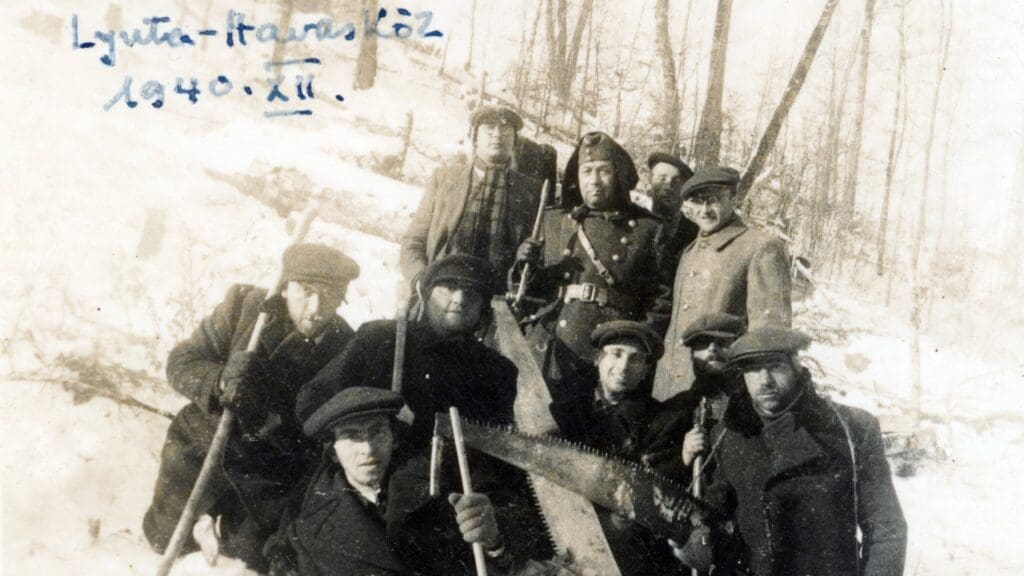

Research into WWII labour service has unearthed several cases of army men who, while perhaps not immaculate individuals, did try to help certain Jews. Such research helps posterity understand the history of labour service better and historians paint a more nuanced picture of what happened.

Netanyahu must not retreat any further, as abandoning his right-wing agenda would threaten the stability of the coalition. Judicial reform in Israel is in fact the last salvation of Israeli democracy, of the rule of the people. Kim Lane Scheppele probably understands this very well—hence her recent attacks on Israel.

‘If we look at the half century after 1945, it was a case of trying to reinterpret the entire Hungarian past, of stigmatising the national idea and tradition. Therefore, we must now rediscover these decades, perhaps the entire 20th century, take possession of them and populate them with our own characters, our own heroes.’

The Germans had demanded the deportation of the Hungarian Jewry long before the German occupation. A note in October 1942, in which German Deputy Foreign Minister Martin Luther summarised his negotiations with Sztójay, the Hungarian ambassador in Berlin at the time, openly mentions the German demand and the fact that it had come directly from Adolf Hitler. According to the text, the ‘handling’ of Jews in Hungary is ‘urgent’.

US Ambassador to Hungary David Pressman caused quite an outrage with his recent decision to invite Jobbik president Márton Gyöngyösi to celebrate the Jewish holiday of Pesach at his residence. Gyöngyösi called for the creation of a list of Hungarian politicians of Jewish ancestry some years ago.

While some of the reservations regarding Easter-related folk traditions articulated from a female perspective can be appreciated, it is questionable whether it makes sense to conduct a Bolshevik-style anti-tradition campaign against rural folk customs. Of course, it is important that this Easter pouring of water in a traditional Hungarian family should be done with the consent of the girls. But it is pointless to pretend that there is any connection between that and the rape culture in the art world.

The fact that the war criminal Apaczeller was a Communist was not mentioned in the press at the time, except for the Jewish newspaper Új Élet…It is perhaps not surprising that the Communist state only dared to leak essential information about the case and that the majority of newspapers remained silent about Apaczeller’s ‘transformation’.

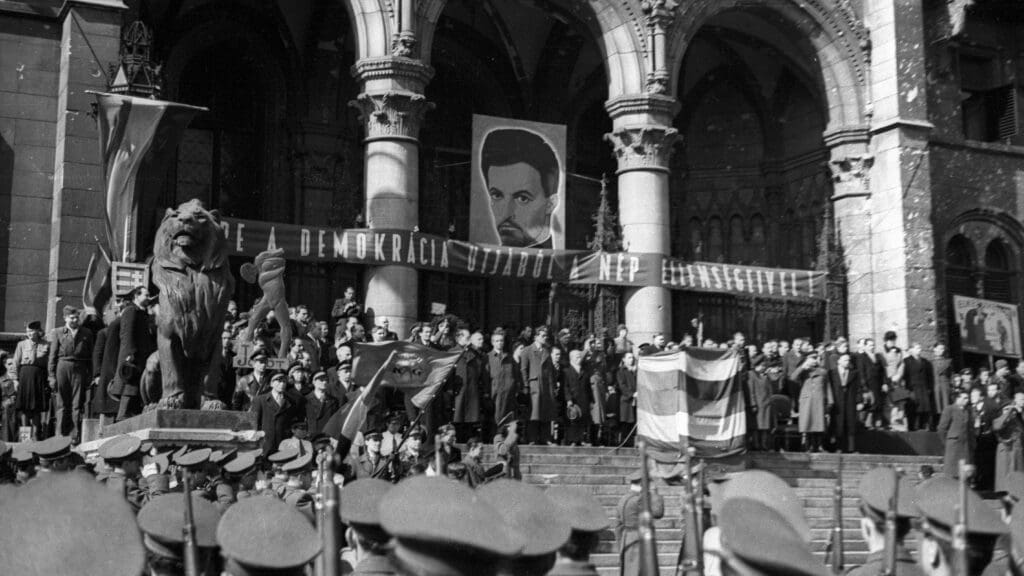

The Communists (should have) had to face up to the fact that their main supporter was the Soviet army, which had first liberated Hungary, only to then occupy it. This was particularly unpleasant in the context of 1848, since the revolution had been defeated by the troops of Tsarist Russia, which aided the Austrians, and the main demand of the revolution was that there should be no foreign troops in Hungary.

How long do we have to put up with the relativisation of the Holocaust, and the irresponsible usage of the ‘Nazi’ attribute? Does the wish to overthrow Viktor Orbán really justify anything now?

‘The significance of Western arms donations is grossly overestimated. This is not helped by a Western press that has sunk to the level of the Pravda, stifling even the slightest attempts at sober analysis and objective discussion.’

Beinart’s reasoning strongly echoes the views of anti-Semites, who also argue that Israel can never be a democracy because of its Jewish character. Their argument goes something like this: Jews are incapable of running a country and, because they don’t want to work, they can only survive by oppressing non-Jews. This view, incidentally, also appeared in German propaganda in the 1930s.

According to the sources reviewed, it is evident that Jewish communities were subjected to the same extent of plundering by the short-lived Communist regime in 1919 as the Christian churches.

Rodrigo Ballester of MCC Budapest warns that we should expect even stronger pressure on gender issues from the EU in the near future. This case underscores the importance of paying close attention to the fine print of EU contracts, as seemingly minor details can have significant impacts on the allocation of funds.

How come, compared to what is going on in Western Europe, Hungary seems to be an island of peace for gay and trans people? How can it be that the Hungarian government is constantly accused internationally of homophobic campaigns, yet it is not here that the murders and rapes, the thousands of atrocities that occur every year, happen, but in the liberal West?

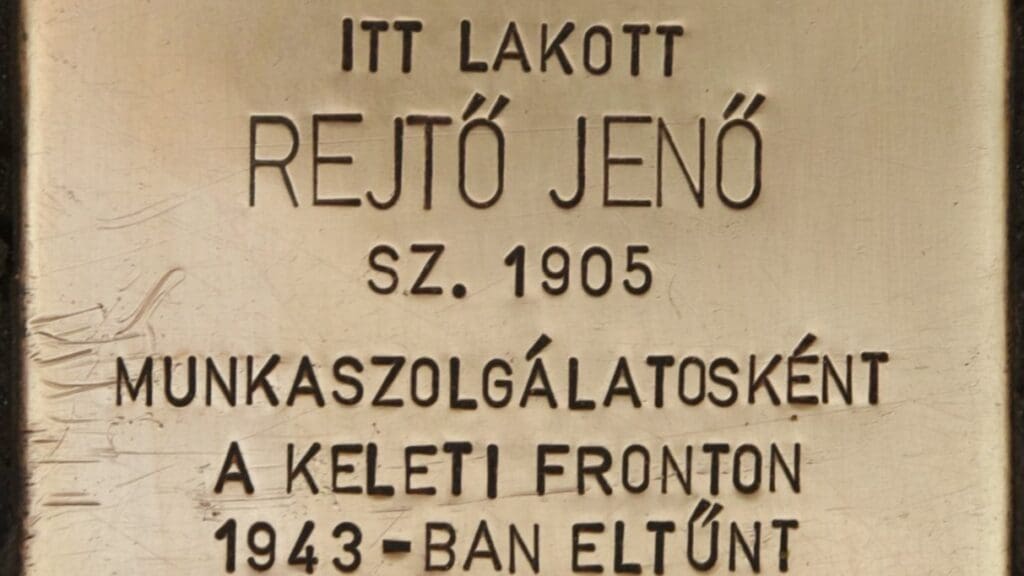

To this day, neither the exact date nor the manner of the death of famous Hungarian novelist Jenő Rejtő is known. ‘P. Howard’ disappeared in a labour camp on the Eastern Front in early 1943.

‘Many of the causes he promoted used to be thought of (by the ignorant) as “right-wing” and have now become almost, or entirely, mainstream.’

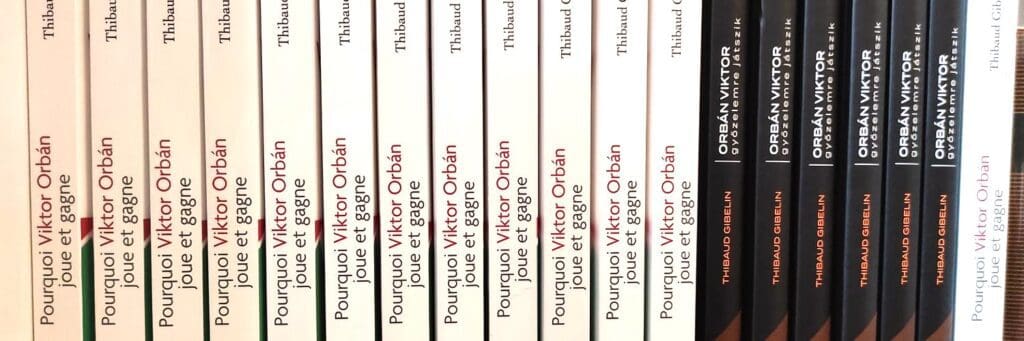

‘The Hungarian prime minister not only understands the people, but is also able to give direction and to synthesise. He can bring the people’s expectations in line with what is achievable.’

‘We need the United States and NATO to say to Russia, “Okay, we get it. NATO will not enlarge to Ukraine and to Georgia.” In my view, that is not a defeat of NATO. That is just common sense.’

Turkey’s relations with NATO have been contentious over the years, but this is not unique among the member states and the parties have always managed to resolve their differences.

Paradoxically, Communist Béla Kun and the contemporary nationalist racists had more in common in terms of their views than the Communist leader had with the social-democratic and the left-leaning bourgeois émigrés.

During the great show trials of the late 1940s and 1950s, the Communists often held small ‘side trials’, which provided ample opportunity to extract and collect further compromising data and testimonies against the primary targets, as well as to conduct silent showdowns and to set the course for later trials. This is how the Archbishop Grősz trial led to the arrest and imprisonment of some 50 people, including well-known Hungarian monarchists.

Under the housing scheme, six thousand flats were handed over to families living in wagons in Budapest alone, and nearly two hundred in country towns such as Miskolc.

Just as some Christians had trouble accounting for their role in the 1918 Aster Revolution and the 1919 Communist coup d’état, some Jews also had difficulty facing their former position in terms of these events.

The majority of the refugees were intellectuals, mostly from Transylvania, followed by those from what is Slovakia, Serbia and Austria today, but there were also some who fled to Hungary from Bosnia-Herzegovina.