The year 1000 is not only memorable for Hungarians: at the turn of the first millennium, unexpected events took place in the whole of Europe, including on the fringes of the continent barely touched by Latin Christianity, in Poland and Hungary, where Christian conversion had been going on for years.

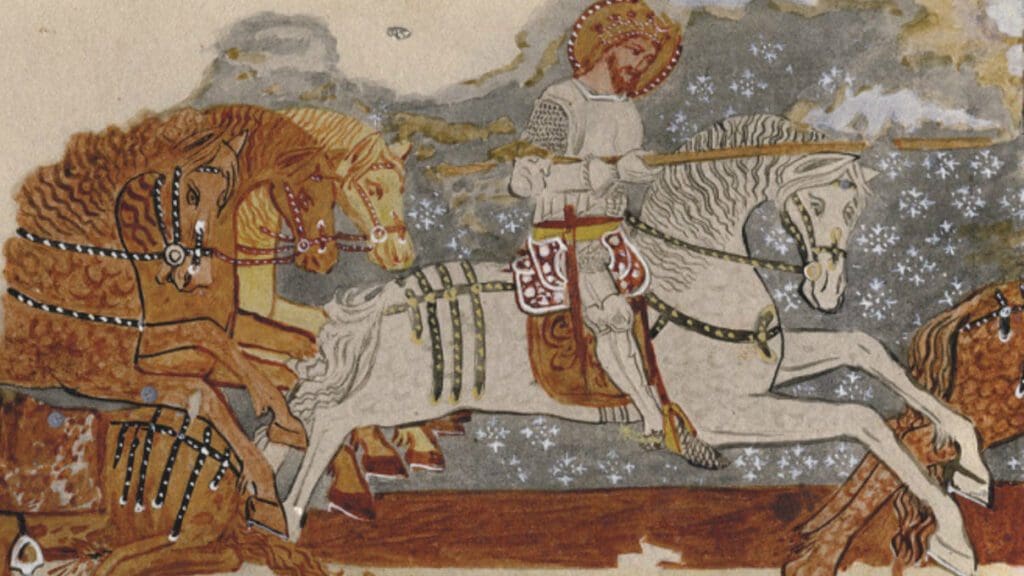

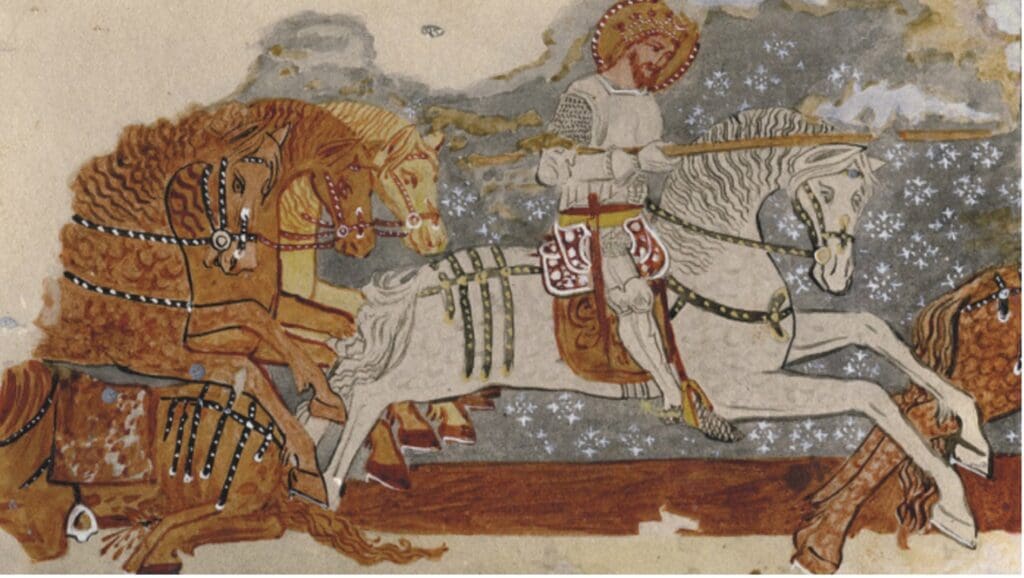

Surprisingly, the earliest royal secular knightly order in Europe was founded in 1326 in Hungary, a country just emerging from civil war, by King Charles I, in honour of St George, the patron saint of knights since the crusades.

His courtly representation, international Gothicism, and the reception of the Renaissance in Hungary can be considered Matthias’ most brilliant achievements, which were also highly appreciated by his contemporaries. It is undoubtedly a unique phenomenon of 15th-century Hungarian history that the Italian Renaissance had such a great impact in the country.

‘The significance pilgrimages had in terms of building clerical and diplomatic relations cannot be overlooked either. A whole slew of abbots, bishops, future archbishops, historians, poets, theological thinkers, and monks later canonised as saints visited Hungary. They brought highly cherished relics, luxury items of the East, and—not least—news with them.’

What is extraordinary about the image of Attila as a ‘Hungarian King’ is not that it has evolved, but rather that it has expanded into a system of arguments with daily political impact, and although it has undergone significant changes, it has survived the 21st century.

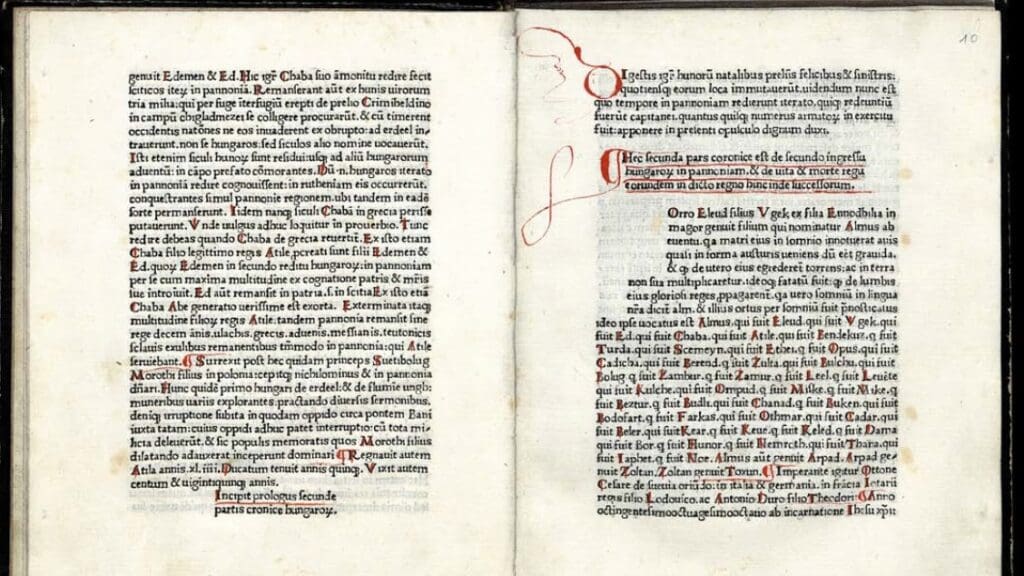

The year 1473 seems incredibly early for printing in several respects, as north of the Nuremberg–Augsburg–Venice line and east of the Rhine–Main line, book printing was not yet feasible at the time. In addition, it was no less rare for a nation’s history to be printed either—the Buda Chronicle, the first printed book in Hungary by 15th-century printer Andreas Hess, can be considered the second of its kind in the whole world.

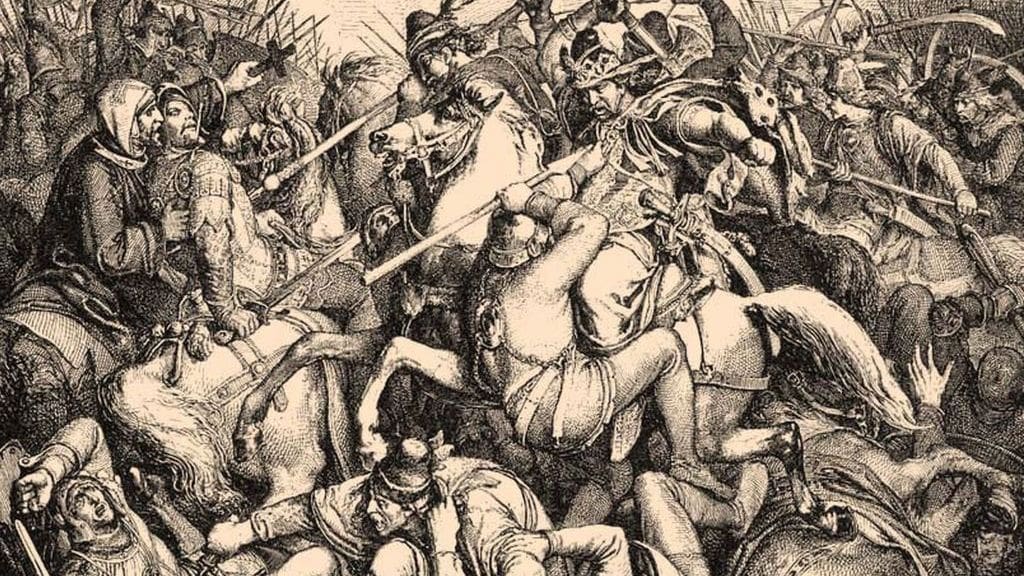

In the last decade, archaeological, archaeogenetic, and historical research into the prehistory and early history of the Magyars has produced results not seen in a long time. The Battle of Pressburg, which often provoked extreme reactions and became a real media event, also played a decisive role in this—of course, in a positive sense.

The concept of the ‘Bulwark of Christendom’ appeared in all border areas where two civilisations and religions came into contact. However, the conscious and regular use of the term is linked to the Italian humanists of the 15th-century Renaissance, who greatly contributed to the formation of the modern image of Europe.

The image of Dózsa in Hungary has undergone so many metamorphoses that it would be difficult to link it to a single political trend or party. He could fit the role of a national hero who took up arms against the Turks under the banner of the Cross blessed by the Pope; a ‘martyr of the proletarian movement’; and a victim warning against the retaliation after the Revolution of 1956 all at once.

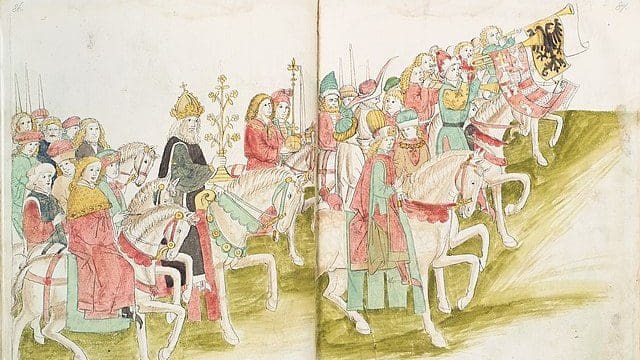

Sigismund of Luxembourg, the ruler who ascended the Hungarian throne in 1387, and whose first wife was the granddaughter of Charles I, could, of course, have heard of his predecessor’s order, and perhaps even followed his example when he himself founded the Order of the Dragon in 1408.

From the perspective of Europe, the Hungarians’ conversion to Christianity was by no means an unbroken continuation of their raids—the Hungarian people was still considered suspicious, barbaric, and prone to paganism for a long time.

Charlemagne’s figure, as well as the myths and legends associated with him, had a great influence on medieval Western European chronicles and fiction, but medieval Hungarian historiography—similarly to Central European—was surprisingly little affected by it.

Keeping the memory of St Ladislaus alive is a common cause. As the organisers of the erection of the equestrian statue of the Holy King said in response to critical comments: ‘The legacy of St Ladislaus is above all the courageous admission of the Christian faith, which is a universal value and part of our European identity.’

Life in the East was not at all easy for the newcomers, as they had to preserve their traditions while developing their identity in a completely new social and religious environment.

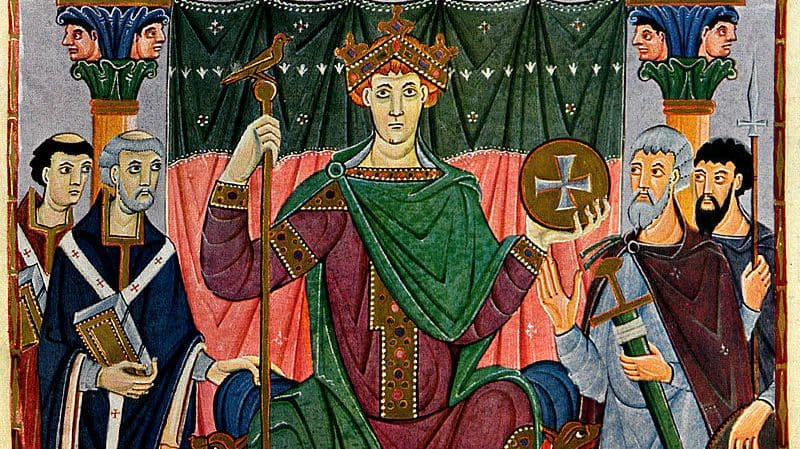

In addition to strengthening the alliance between the Kingdom of Hungary and the German Empire, Blessed Gisela’s marriage to St Stephen permanently committed the country to Western-style Christianity and development.

The more than two-metre-high equestrian statue in the Bamberg Cathedral has been a real tourist attraction since the 18th century, not least due to the horseman’s mysterious identity.

It may be surprising that Muslims could survive in a Christian kingdom for centuries, but their linguistic and religious separation was exactly why they did not threaten the predominantly Christian society.

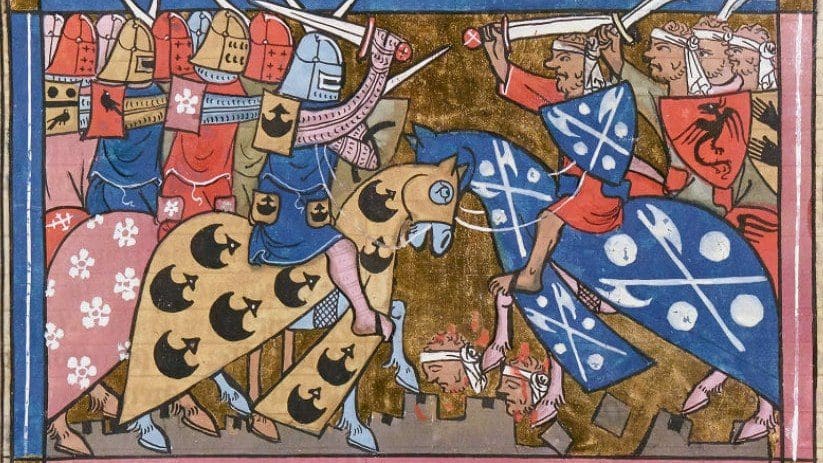

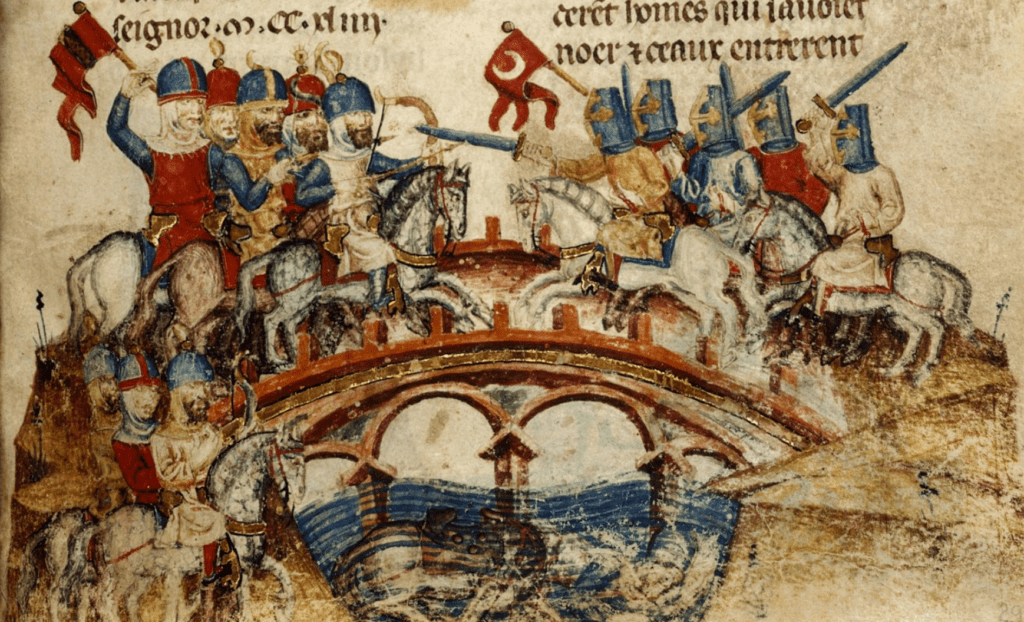

Zadar was a Western Christian town with a rich history, and at that time it was once again under the authority of Emeric (Imre in Hungarian), King of Hungary (1196–1204), who himself had taken the crusader’s vow.

The defence mechanism of the Christian world was triggered incredibly quickly in 1241, but due to various conflicts of interest, mostly international, it slowed down just as quickly and then became totally paralyzed.

Is heroism, self-sacrifice and risking one’s life for a noble cause indeed just a dream that flesh-and-blood people would not be capable of? Luckily, no.

The grave Hungarian defeat was embellished and embedded in Hungarian historical memory as a sort of victorious episode.

Hungarian Conservative is a quarterly magazine on contemporary political, philosophical and cultural issues from a conservative perspective.