‘In the modern, global-technological civilization based on the parallel structures of technical rationality, the idea of freedom still arises as an “abstract freedom” that is allegedly “the same for everyone”. But, regarding recent facts and conditions, this concept of freedom has lost all realistic content. Following the example of the idea of philosophical atomism, the human individual is still imagined as an atom, and from this social atomism it also follows that the modern individual is no longer an organ of a transcendental reality, but rather the social “whole” is derived from this collective of individuals.’

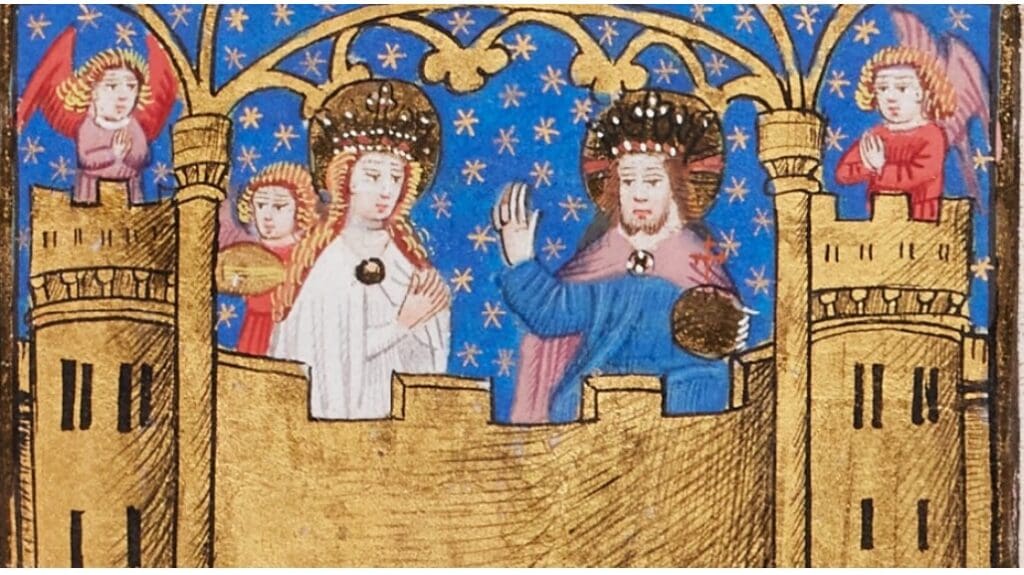

The Hungarian and Turkic people (or rather, peoples) are connected in many cultural and even genetic ways. The Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus called the Hungarian conquerors ‘Turks’, and the sons of the House of Árpád (Turul gens in medieval Hungarian sources) were later called ‘Princes of Turkey’ by the Byzantines. In the origin myth of the Hungarian royal dynasty, the ‘Turul bird’ is also of Turkish origin, as the symbol of the Sky and of the supreme God of Turkish myths, where it appears as toġrïl or toğrul.

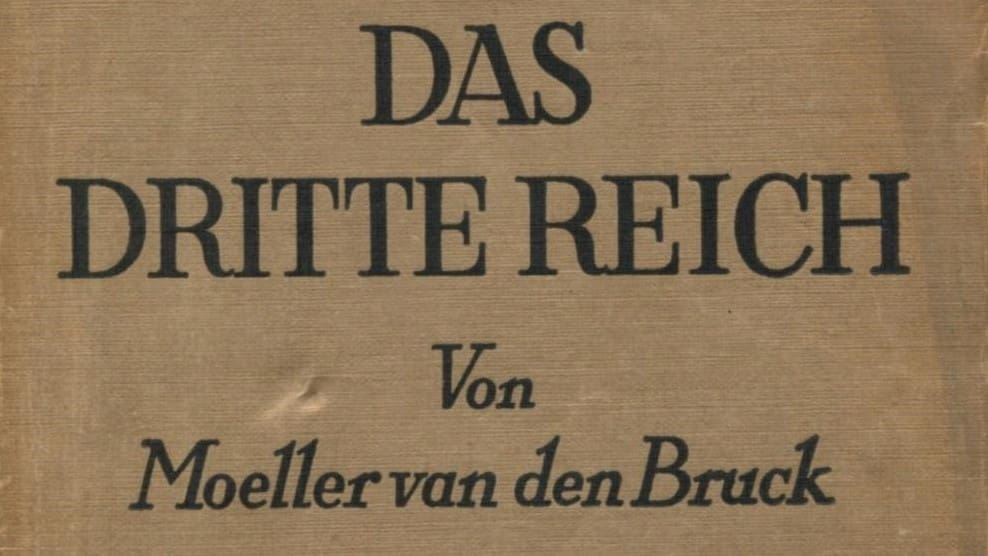

‘The phenomenon of the conservative revolution was partly a consequence of the collapse of the German state (formed in the 19th century by Bismarckian ‘state-building) after the First World War, and was born out of its internal and external crisis, its defeat in the war. In the broader context of ideological and political history, however, the conservative revolution, albeit a cataclysmic one, cannot be seen as the consequence of a single political event.’

‘Various machines also existed before modernity: the builders of the Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages also had considerable engineering and pragmatic knowledge, so it was not that they lacked the necessary knowledge, but above all they lacked the formulation and application of the machinic idea. The view that we must ceaselessly improve the human destiny by taking human destiny “into our own hands” is a historically new development, not much older than a couple of centuries at most.’

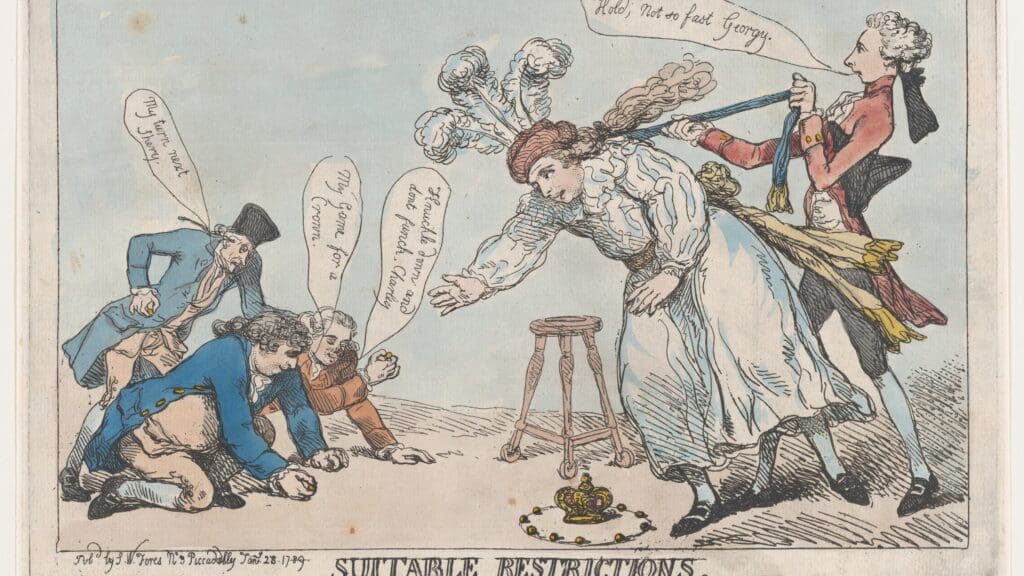

‘In today’s democracy, authority is in crisis because real authority cannot follow from mere quantity. Quantity is always relative, and the thing what is ‘never identical to itself’ cannot awaken the intuition of true respect, true authority, and true supremacy. A real authority is someone to which, as Edmund Burke writes, one can “freely and proudly submit” himself. Real authority would also require the recognition of the legitimacy of a transcendental sphere, beyond the world of relativity.’

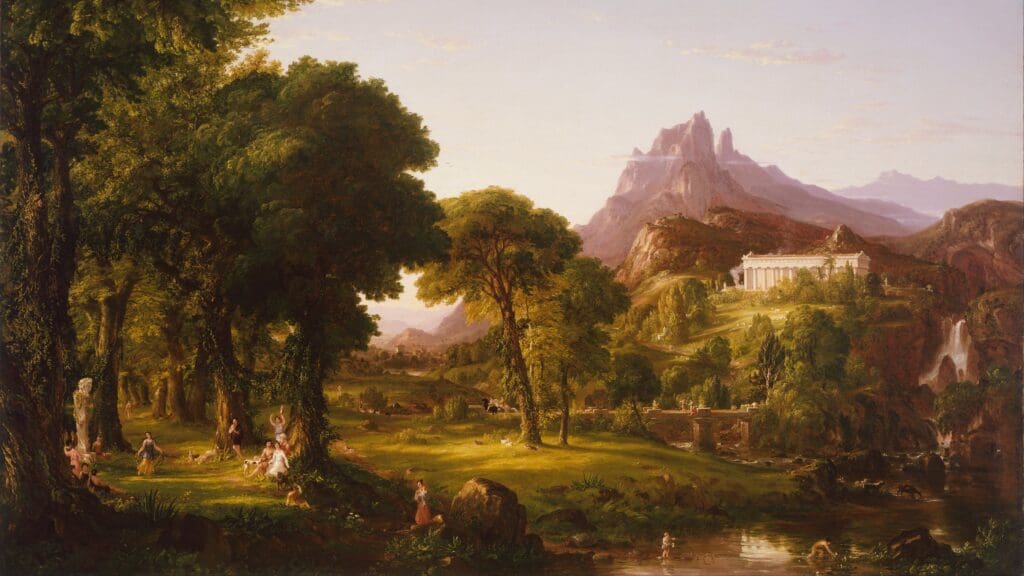

Spengler’s work has not lost any relevance over the century that has passed since it was released, but rather has become increasingly significant: it is now one of the inescapable foundations of the philosophy of history. Many of the predictions concerning the fate of humanity—especially the distinctions Spengler drew between culture and civilization—do not seem to contradict the major ideological, political, artistic, cultural, social, and economic trends of the present day.

The Hungarian nobility—not only the Seklers—considered themselves to be of Hun-Scythian origin throughout the Middle Ages and partly during the modern period, and although the Scythian question should be examined separately from this fact, it is obvious to us that this sense of origin—in the light of the latest archaeogenetic results— coincides with medieval chronicle tradition and the idea of a Hunnic origin was probably not ‘adopted from Western chronicles’, as earlier research suggested.

‘Before the corrosive spirit of purely rational analysis without synthesis became widespread, societies were conservative because they perceived the non-variable essence behind phenomena not only through their most eminent intellectuals but also collectively. The ‘‘men of the spirit’’ in each age had a particular connection with this spiritual essence, a relationship of a different quality than most of society. This is the origin of true priesthood and also of true ‘‘intellectuality’’.’

Paradoxically, it seems that democracy can only sustain itself and protect itself from collapse, (tyranny and chaos) precisely by what is not democratic in it. It seems that it is always easier to justify democracy with a quasi-mystical hypothesis than with one that starts from the existing conditions of political realities. In democracy, we can clearly say that there is a huge gap between the ‘ideal’ and the ‘realistic’ and precisely because of this democracy definitely needs a ‘leap of faith.’

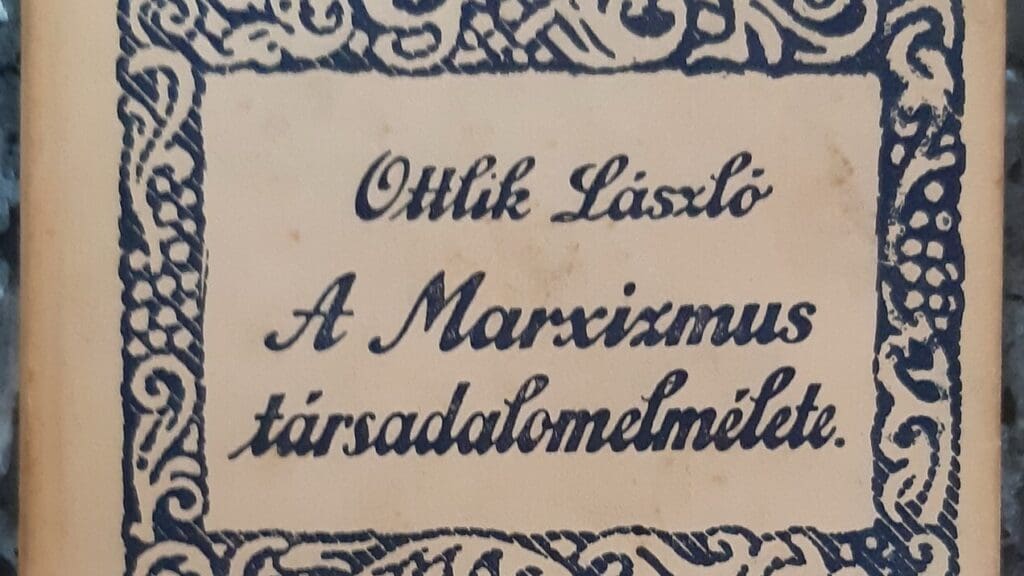

Political philosophy that is clearly separated from legal philosophy could not really take root in Hungary either in the Renaissance or in the 18th–19th centuries. Outstanding experiments such as certain writings of Count István Széchenyi or Aurél Dessewffy, the ‘Ruling ideas’ of Baron Eötvös or some excellent political essays by Zsigmond Kemény remained isolated experiments. Ottlik is one of the first Hungarian practitioners of political philosophical thought who can be integrated into the Western traditions of political thinking.

The most characteristic phenomenon of modern industrial capitalism in Chesterton’s assessment is the development and creation of the so-called ‘trusts,’ economic monopolies that deliberately strangle small businesses, while not infrequently operating as a criminal consortium, intertwined with political and state power.

‘The duality of God and man is the most fundamental reality of existence: a reality which can structure and constitute all relations of human beings. This principal duality is the source of everything: epistemology, ontology, moral philosophy, politics, and—of course, as Martin Buber said before—the “Ich und Du” relationship is the source of the true philosophy of religion and theology. This point of view is close to the most fundamental personalities of modern Catholic thought, and the philosophy of neo-Thomists such as Jaques Maritain and Étienne Gilson. According to Molnar, this “I and Thou” is the message which the true Christian philosopher has to protect against modernity’s aggressive immanentism, which could be materialist or spiritualist, too. The essence of this immanentism is the dissolution of transcendence into man’s imaginary “divinity”—to reach the deification of the world.’

In his short speech introducing the international conference, head of the Thomas Molnar Research Institute, historian of political thought Károly Attila Molnár highlighted that as a Hungarian emigrant, Thomas Molnar tacitly accepted the values of liberal democracy in the United States, but criticized its ideological foundations and pointed out the dangers of ‘Americanization’, the consequences of economic liberalism and social engineering.

‘When Marx explained the philosophical foundations of dialectical materialism, he first of all referred to the “development of the natural sciences”, just as the representatives of today’s New Atheist movements like to claim that “science has surpassed God” when explaining their theories.’

‘The term “liberal” was undoubtedly originally associated with the aristocratic spirit of freedom and generosity (in Latin: liberalitas), which, recognizing a natural hierarchy among individual beings, finds diversity welcome and does not desire to make things equal in all circumstances. Since many of the theoreticians of liberalism did not take this principle into account, it can be derived that most liberals strongly oppose the principle of authority.’

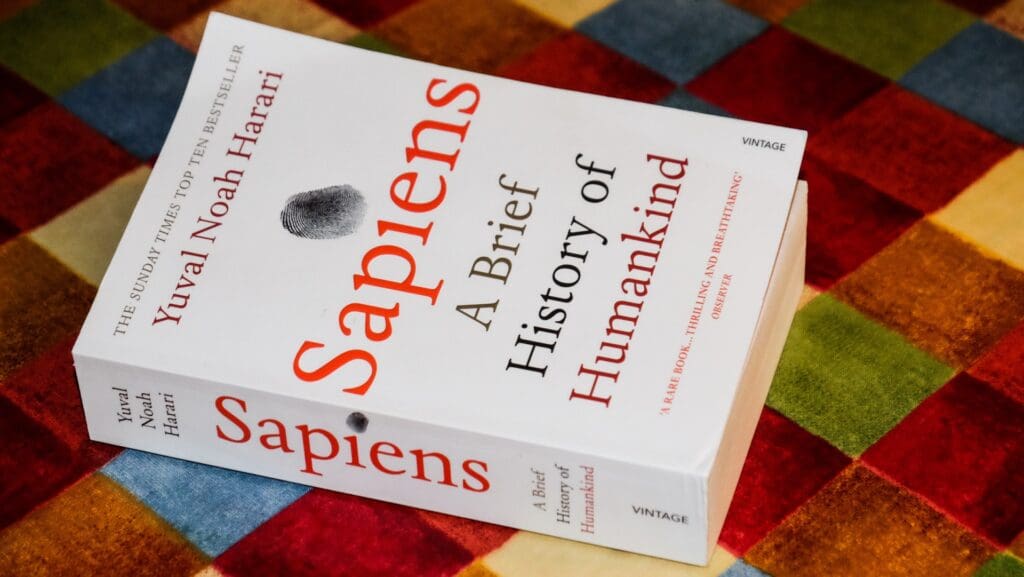

‘Transhumanism—at least in the form in which it is represented and explained by Harari—stands, above all, on the ground of anti-religion. The mechanical man, who becomes immortal, as the meaning and purpose of history, is above all the opposite of the eschatological perspectives of all religions.’

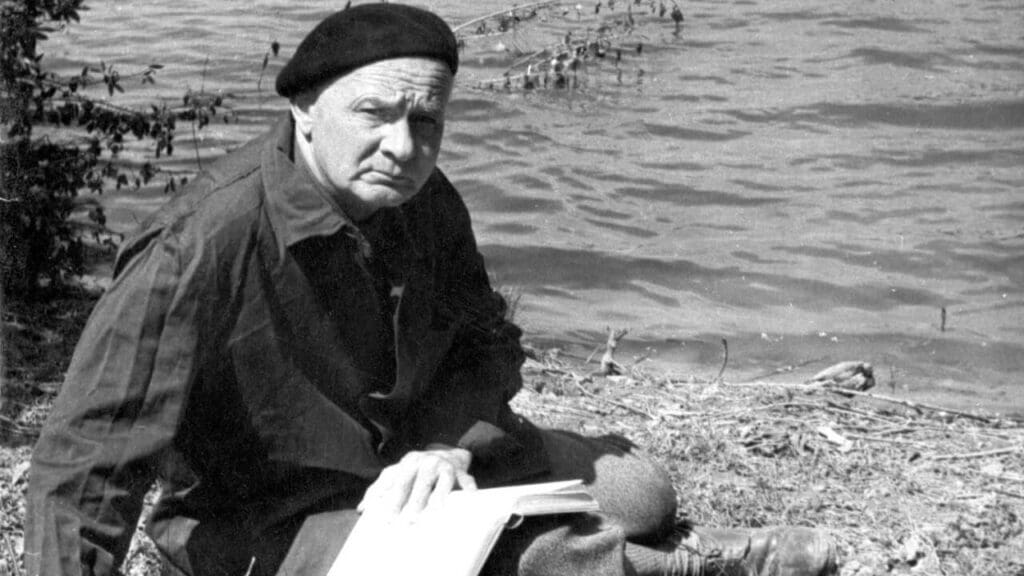

Hamvas’ focus on metaphysical questions in the field of philosophy did not simply stem from his belief in God or his religious predisposition, but rather from this critical attitude towards modern natural science, from a ‘scepticism against scepticism.’

Oakshott’s individualism differed from the individualism of liberalism, which rejects traditions. Oakeshott assumed that individuality can only be created in some context, and that freedom can only be enjoyed in order. It is not the acceptance of authority, but the absolutization of reason that destroys individuality, as he explained in his preface to Hobbes’s Leviathan.

‘If a society is exhausted in immanence, if people are not aware of the finitude of their own life, knowledge, and power, and if every goal of the person, the state, and politics is directed towards material interests, then the state will be exactly that Civitas Terrena, which is also Civitas Diaboli. Everything is justified by the stronger interest (Hobbes), pragmatism and secular science serve the immanent power goals of the great Leviathan, while real wisdom, taste, and arts, that make life pleasant (or just bearable) start to decline, wither, dissolve into a gigantically increased bureaucracy called the state.’

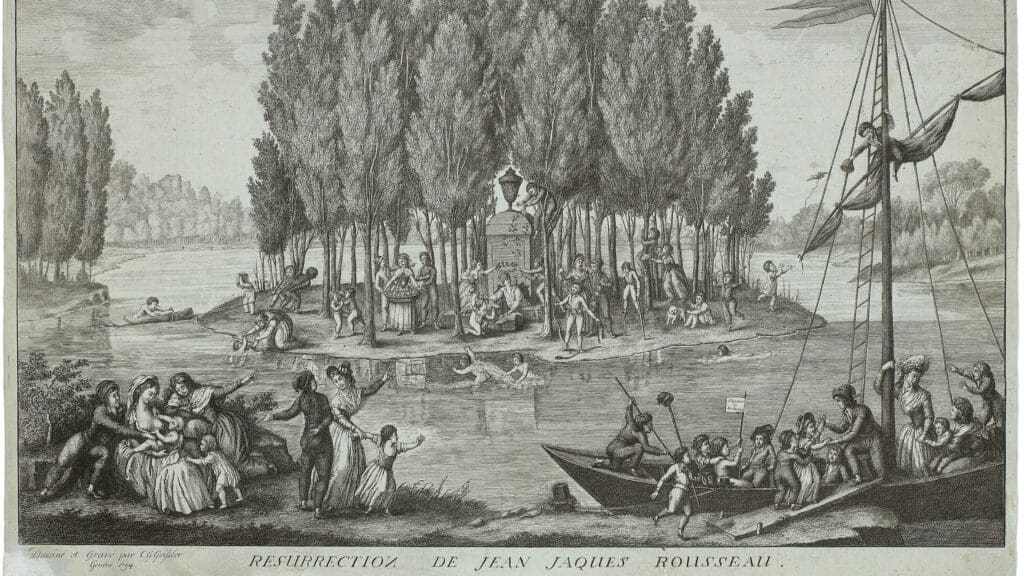

The lack of humility, modesty, the lack of deference to one’s superiors, the lack of discipline and respect are the main causes of most of the political and sociological problems of modernity. After all, according to the blind believers of progress, sailing never ends. However, according to conservatives, there is no such thing as an island of Utopia. Their problem in politics is not the search for an island that doesn’t exist, but: ‘[h]ow to get the disgruntled crew to help keep the ship of the state afloat, to keep it from capsizing and being shipwrecked?’

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of the work is that its author is brave enough to challenge completely the established thinking and vision that takes historical progress and the associated rise of liberalism for granted.

‘The disappearance of the aesthetical representation of power from politics parallels the egalitarian rhetoric of the rationalists. The representatives of power often emphasise today the ‘non-existence of differences’ with their own clothing and behaviour, although anyone who is not completely naïve knows in their heart—or at least from Aristotle—that the real differences can never be eradicated between the governor and the governed.’

According to the most fundamental concept of the Holy Crown doctrine, everyone who has political rights in the territory of the country is a member of the crown, a part of its ‘body’.

Although we clearly cannot consider László Németh a conservative thinker in the ‘classical’ sense, we can still regard him as an interesting writer. He is worthy of our attention especially with regard to his critique of technocracy. In fact, he expressed valuable insights regarding the dominance of technical rationality, but also in many areas of culture, therefore his works can serve as valuable food for thought for conservatives who are willing to expand their horizons in new directions.

As long as people are conditioned to become consumers by advertising applied on an industrial scale, and as long as material comfort and interest are above all else, the environmental crisis will not be solved satisfactorily and especially not with more technology.

As philosophical materialism and the resulting transhumanism are atheistic systems of thought, it is extremely important for Harari—as it is for Dawkins—to deny the idea of God. Just as Richard Dawkins replaces a transcendent creator with the theory of evolution, so does Harari use evolution as a justification for the theory of transhumanism.

Europe’s contemporary society, the current system and operation of the European Union, its political, social and more deeper tensions—affecting the whole of human existence—all prove that the still popular phrase ‘progress’ is losing its catchword character just as more and more people become disillusioned with the ‘big projects of globalism.’