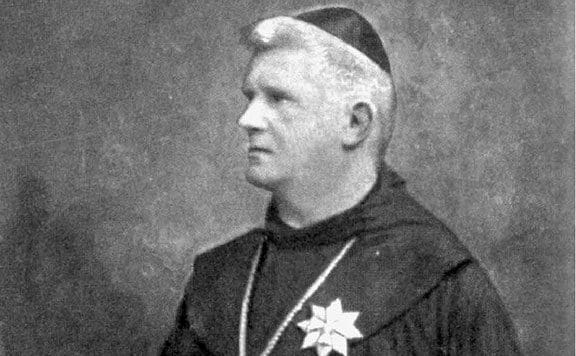

The diaries of Franciscan friar and military bishop István Zadravecz, an important Christian leader during the interwar period, were published during the Socialist era, edited and commented by communist historians in a way to strengthen the picture of a shady, evil and antisemitic, reactionary priest.[1] The document, which he had led up to the late twenties, projects the image of an irritable and highly nationalistic person. Apologetic literature on the friar is either not available, or does not mention the friar’s activities during the thirties or the forties. The only obituary published after his death was a Nazi (Arrow-Cross) article, which lauded the friar for having fought Jews all his life.

Contrary to all these works, there is a previously unexamined documentation on the friar available at the Budapest Archives and the Hungarian Archives of the Franciscan Order. While this material certainly confirms that, at one point, Zadravecz used to be a nationalistic and antisemitic preacher, it also proves that in spite of his early views, he launched a daring mission for saving Jewish lives during the Holocaust. Testimonies by Jewish survivors of the Shoah prove that Zadravecz actively assisted in saving at least a dozen lives, and further documents seem to suggest that he contributed in saving many more. The story also sheds light on the dubious workings of the post-war People’s Tribunals.

Zadravecz launched a daring mission for saving Jewish lives during the Holocaust

Zadravecz was first arrested in May 1945, after the end of the Second World War in Hungary. By September, the indictment was prepared by the People’s Prosecutor, which accused Zadravecz of incitement against the Soviet Union. Zadravecz’s first trial was in November 1945, which ended with his sentencing in April 1946: the Council of the Budapest People’s Tribunal sentenced him to five and a half years in prison at first instance, but in September he was released by the National Council of People’s Courts (NOT). In February 1947, he was sentenced to four years in prison. At a new trial, he was sentenced to two years in prison, which was considered fulfilled by his time spent in arrest, but he was interned in a small farm in the countryside (a common method of punishment by the communists).[2]

Here, I am analyzing various testimonies and depositions made during his many trials along with his speeches and articles appeared in the daily press at the time. During the processes, Zadravect was accused of having supported the Arrow Cross regime. In reality, he was well-known for his opposition to the Arrow Cross, and stated that he would never bend in front of the Arrow Cross or Hitler’s “bent cross”, only “Christ’s cross”. When in 1940 a group of Arrow Cross miners went on strike and brought production to a halt, Zadravecz accused the far-right party of ‘trampling on the Hungarian banner’. ‘I was always against the Arrow Cross’, ‘my whole heart and mind were against it’, he later testified.[3]

‘The Jews are our brothers, we must not hurt them’

While the charge of supporting the Arrow Cross was quickly dropped, Zadravecz was also accused of antisemitism. The friar claimed that he had ‘never been an anti-Semite’[4] – a statement that could not have been true, in light of his very own diary[5] –, but an altar boy of Jewish ancestry, Miklós Csillag did, in fact, testify in court that Zadravecz had been opposed anti-Jewish legislation ever since 1938. Another Franciscan friar, Mór Majsai testified that Zadravecz was opposing anti-semitism.[6] Supporting these statements, we can cite two speeches of Zadravecz from the year 1939: in one of them, he said that Hungarian life was based on ‘worshipping God, loving one another, regardless of rank, race or creed’,[7] while in the other he spoke about the Jewish origins of Jesus. ‘Christ was first and foremost the son of God. There is no room for racial or blood theories, history itself forbids it’.[8] Even in 1942 he spoke in front of his followers that ‘the Jews are here to stay, they played among us [as children], they enjoyed our sunlight, breathed the smell of our flowers, worked with us and assimilated here […] The Jews are our brothers, we must not hurt them’.[9]

When the Nazi troops occupied the country, the friar was holding a holy mass in rural Salgótarján. Zadravecz was immediately warned not to return home, but to hide because he would be arrested by the Gestapo, yet he did not go further than the Franciscan convent outside of Budapest. The Germans did search for him there, but the other friars replied that he was not there and so the Germans—probably the Gestapo—left.

In early April, Christian believers of Jewish descent—just like all Jews—were forced to wear a yellow star. At a mass in Buda, Zadravecz personally tore off the yellow stars from his followers. In his sermon he said, ‘The humiliated Christ, the lover of millions of all peoples and nations, has become a despised Christ, who shines like white snow among the mockery. […] Oh, all of you who have been ridiculed and mocked: accept the compulsion with the light of Christ! […] We unbrokenly love and appreciate in you the sacred and indelible mark of baptism […] And ye shall carry the mockery with the spirit of Christ. […] I proclaim to you by faith the glorification of Christ, the glorious resurrection’.[10]

After the mass, he invited his followers of Jewish descent to have breakfast in the parish. The friar claimed that apart from his above quoted message, ‘I have preached the same faith in countless other places,”. His adherents testified in court as follows, ‘At a time when the Jews were required to wear the yellow star, the accused protested against the myth of race and blood repeatedly, saying—among other things—that it only made society upset, afflicted families, and tore husbands, wives, brothers and sisters apart.’[11]

Zadravecz’s courage did not wane after 15 October Arrow Cross coup. On the feast of Christ the King, two weeks after Ferenc Szálasi took power, the friar prepared to give a radio speech against the suppression of human rights and the ‘kind of Christ the king’. His speech was obviously banned, but in his church sermon, the friar expressed his indignation at the renewed persecution of the Jews, which had now spread to Budapest: ‘We have sinned, we have sinned very much in our laws, in the laws that seriously violate the laws of God, the rights of our neighbours […] We have sinned in our unrighteousness […] […] We drag groups through the streets, crying children, pale mothers […] it’s a moral disgrace! Neither God nor man could create a law to sanctify it!’[12] Although his other words were not recorded, his followers were struck at how “wildly” he scolded the events of that time. At this time, many advised the friar to hide, for the Arrow Cross would no doubt come for him. Zadravecz again did not flee, and this time no attempt was made to arrest him. He also visited and comforted Christian families of Jewish ancestry in the so-called “star houses” – that is, Jewish houses marked with the yellow star. According to one survivor, at the end of October 1944, when the Arrow Cross were forcing the deportation of the Jews of Budapest go the western border, Zadravecz said in front of his followers: ‘My dear brothers, the Jews are not guilty of murdering Christ, do not let them be taken away, they are not guilty!’[13]

PHOTO: FORTEPAN / LISSÁK TIVADAR

Zadravecz was seen as a crucial link between the origins of the interwar right-wing system and its final days, therefore, he had to go

As we have seen in the introduction, this evidence hardly had any effect on the communist court, and Zadravecz was hauled off to prison, and then to rural interment. Sándor Haraszti – then a communist journalist, later an ally of Imre Nagy – summarized the importance of Zadravecz’s arrest as follows: the interwar right was ‘led by Miklós Horthy’ and his “crusaders”, ‘Zadravecz with his Bible’, who ‘educated the murderers with machine guns […] Rajniss and Szálasi’, the Arrow Cross men who ‘betrayed our homelands and who led it into destruction’, and who ‘our People’s Tribunals are now sentencing in a row’.[14] Zadravecz was seen as a crucial link between the origins of the interwar right-wing system and its final days, therefore, he had to go.

As one flips through the pages of the friars 1927 diary, little if any shows of the courageous and philanthropic side of the Franciscan priest. With his concluding lines, the friar casts dark curses on his opponents;namely, the Protestants, and words his hope that he would live longer than all of them, so that he could ‘die with a laughter, in the knowledge that my evil-doers have all went to hell’.[15] The first part of his wish was granted to him; with his death in 1963, he lived longer than most important figures of the interwar period. And by then, he probably did not seek to see the second part of his wish fulfilled. According to his Franciscan brothers, he spent his last years contemplating whether he was worthy of the love or of the scorn of God. ‘We need to love Christ’, the elderly friar kept repeating daily. ‘There is nothing greater than that. Love lasts forever. I forgive you all.’[16]

[1] György Borsányi (ed.), ‘Páter Zadravecz titkos naplója’, (Budapest: Kossuth Kiadó, 1967).

[2] For the court documents on the Zadravecz case, see Budapest Főváros Levéltára (Budapest Municipal Archives), VII.5.1950.2344.

[3] László Bernát Veszprémy: ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni!” – Zadravecz István és a holokauszt,’ Sapientiana, 1 (2016), 78–91.

[4] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 84.

[5] Borsányi, ‘Páter Zadravecz’, 43, 129, 188.

[6] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 84–85.

[7] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 85.

[8] István Uzdóczy-Zadravecz, ’Karácsony’, Nemzeti Figyelő (24 December 1939), 1.

[9] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 85.

[10] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 86.

[11] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 86–87.

[12] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 87.

[13] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 88.

[14] Haraszti Sándor, ’Így kezdődött’, Szabadság, (24 November 1945), 2.

[15] Veszprémy, ‘„Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni”’, 91.

[16] Magyar Ferences Levéltár (Hungarian Franciscan Archives), Zadravecz material. Lad. 1. Text titled „Uzdóczy-Zadravecz István püspök vértanúsága”, 1–2.