The 60th quadrennial presidential election in the United States is in 11 weeks, less than three months away. As the campaign season is heating up, let’s take a look at the peculiar election of 1824, which prompted the foundation of the Democratic Party, in power in the United States today.

John Adams was the first and last member of the Federalist Party to serve as President of the United States. While George Washington was more aligned with the Federalists, he was also against political parties as a whole, so he is one of the two US Presidents who served as independent (the other being John Tyler, who was expelled from the Whig Party shortly after he took office in 1841).

The back-to-back presidencies of Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, all three honouring the Washingtonian tradition of stepping down after two terms, have left the Federalist Party in the dust. So much so that in the 1820 election, the Federalists did not even nominate a candidate. Thus, 19 per cent of the popular vote went to a talented fellow named ‘No Candidate’.

A number of factors contributed to the demise of the Federalist Party.

One: some of their policy proposals were adopted by the Democratic-Republicans. The Jeffersonians were originally against a standing federal army and a national bank based on their anti-federalist principles. However, once they took power in government, they realized the pragmatic necessities of them, and ended up implementing them anyway. Two: two major foreign policy successes happened under Democratic-Republican presidents. President Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase, and acquired 828,000 square miles of land from Napoleon’s France in 1803 for just $15 million. President Madison won (or, to be more precise, did not lose) the War of 1812 against the British, from 1812–1815. The subsequent period of heightened patriotism and optimism in the United States is known simply as ‘the Era of Good Feelings’. And, finally, three: Federalist leaders, disgruntled by their series of election losses, gathered in Hartford, Connecticut in 1814 for a convention where they even floated the idea of secession. That’s right, it was the New England states, the Federalist stronghold, that first proposed seceding from the Union, something Southern states actually followed through decades later. News of the Hartford convention greatly damaged the Federalist Party’s reputation with voters.

So, when it came to the 1824 presidential election, it was four candidates from the Democratic-Republican Party that faced off against each other for the presidency.

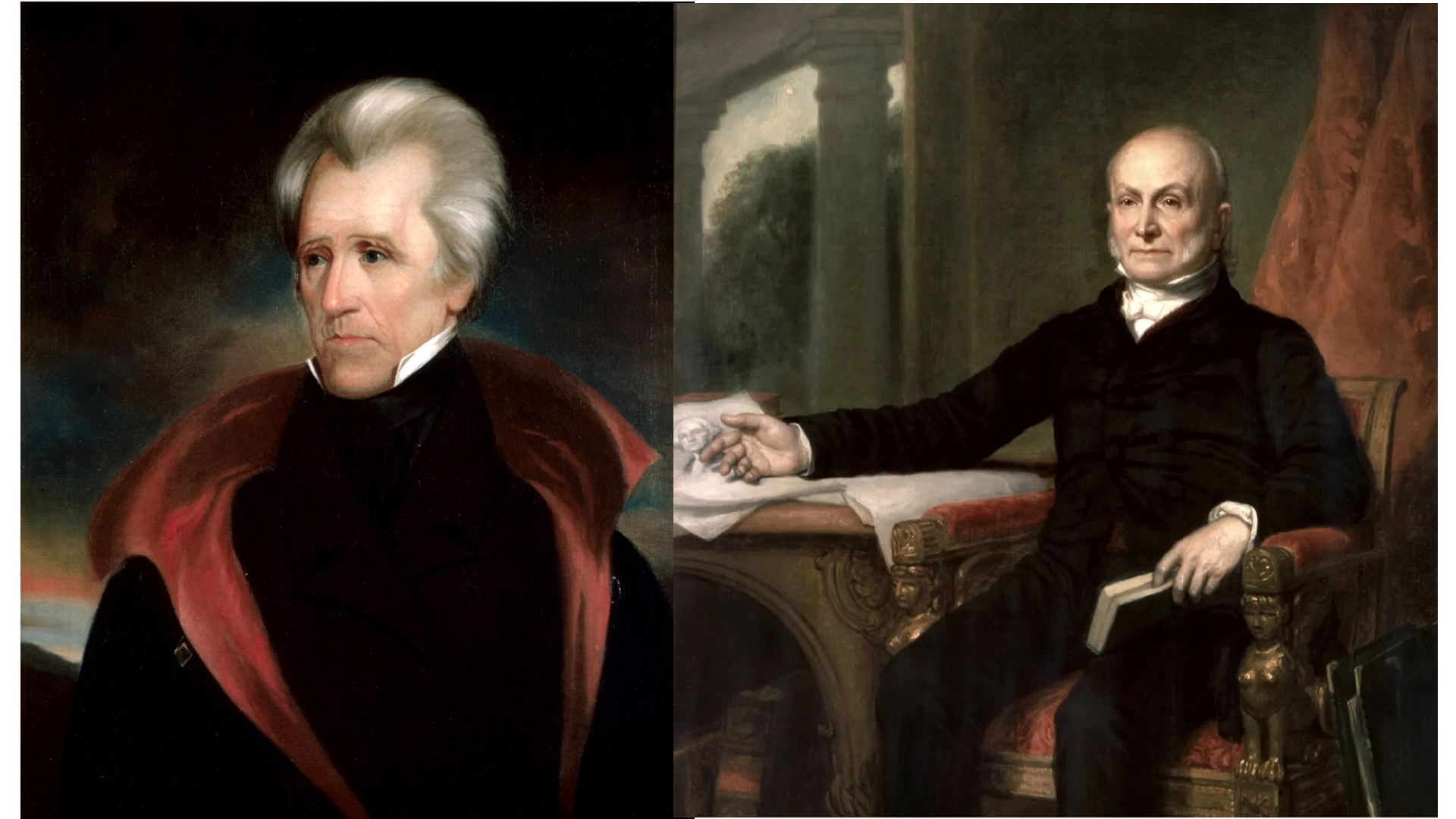

They were: Andrew Jackson from Tennessee, a Major General in the US Army; John Quincy Adams from Massachusetts, son of former president John Adams, who was the sitting Secretary of State; William H. Crawford from Georgia, the sitting Secretary of the Treasury; and Henry Clay from Kentucky, the serving Speaker of the House.

Of the four candidates, War of 1812 hero Andrew Jackson was somewhat of an outsider. While he was elected to both the House and the Senate from Tennessee, he ended up resigning both times after around six months because he found his Washington jobs ‘too boring’. Henry Clay despised Jackson. He called him a ‘mere military chieftain,’ a bloodthirsty brute wanting to become a tyrant. Jackson, however, was seen as the champion of the common folk. One of the major achievements of Jackson was starting the process of all states picking their electors by popular vote, and eliminating the requirement of property ownership for voting.

John Quincy Adams was the polar opposite of Jackson. He was the son of President John Adams, and was involved in foreign diplomacy missions even in his teenage years. He favoured an elitist approach to democracy; as well as Henry Clay’s protectionist-federalist economic policy known as ‘the American system’. His policy consisted of high tariffs and a high amount of federal spending on public infrastructure. Jackson, however, opposed high tariffs, thus protecting the interest of the agrarian Southern states.

In the 1824 election, Andrew Jackson ended up winning both the popular vote and the electoral vote—however, he still did not become President.

That is because he failed to win a majority of the electoral votes, taking ‘only’ 99 out of the 261 total at the time. Thus, this election went to Congress, the second and last one to do so after the election of 1800, which we covered in the last article.

There, House Speaker Henry Clay was able to use his influence to get John Quincy Adams elected instead of Jackson, while John C. Calhoun from South Carolina was elected Vice President (who, interestingly, was also Jackson's running mate). In return, President Adams made Clay his Secretary of State, a move which many dubbed ‘the corrupt bargain’. Jackson was among those enraged by the developments. He felt he was unjustly robbed of the presidency.

The furious Jackson came back for revenge and convincingly defeated President Adams in the 1828 election. In 1832, he broke away from the Democratic-Republican Party formally as well, founding the Democratic Party with his second Vice President Martin Van Buren, the party that occupies the White House today.

Related articles: