Among the Hungarian national holidays the celebrations of the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–49 against the Habsburgs—15 March and 6 October—are of particular importance and still retain a certain topicality. They recall a turning point in Hungary’s history that can only be compared to the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, the foundation of the Hungarian state, 1945–1947, and the turning point of 1989–1990. 1848–49 has become one of the cornerstones of modern national identity, as they were a time of individual liberation and national self-determination. The country’s defining experience of 1848–49, apart from the armed struggle, was the liberation of the serfs and the establishment of equal rights for citizens. 1848–49 was a life experience for society as a whole. With its revolutionary social reforms, the War of Independence was the initiator of civic transformation, and its struggle for self-defence became part of the national mythology. It was an integral part of the European revolutionary wave of 1848, too, but it was the only one of them to reach the point of successful military resistance.

On 15 March, the beginning of the 1848 Revolution is commemorated with fierce speeches by politicians and noisy rallies, while on 6 October, the execution of military and civilian leaders of the defeated struggle is remembered with silent processions and candle-lighting. This is already a quieter, more subdued anniversary, rather a day of mourning, not far from All Souls’ Day in early November.

‘1848–49 became one of the cornerstones of modern national identity, as they were a time of individual liberation and national self-determination’

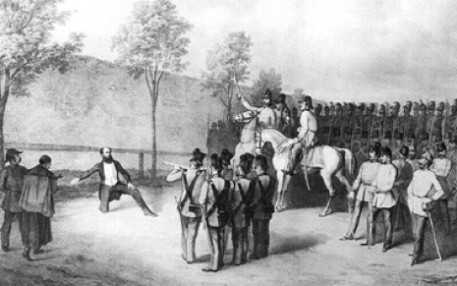

173 years ago, on this day in 1849 in Arad (now Romania), thirteen generals of the Hungarian army were executed. Posterity refers to them as the 13 Martyrs of Arad, but there were actually seventeen of them, as executions were carried out in Arad already in August 1849 and later in February 1850 as well. The court-martialled officers were primarily charged with armed insurrection, which was classified as treason for those who remained in service after the Hungarian Declaration of Independence, that is, the declaration of the dethronement of the House of Habsburg–Lothringen on 14 April 1849. In September 1851, leaders who had fled abroad were hanged symbolically, including Lajos Kossuth, the country’s governing president, and army colonel Gyula Andrássy who later became prime minister of the Kingdom of Hungary after 1867 and foreign minister of the Austro–Hungarian Empire after 1871. Eventually, tens of thousands of officers were conscripted as privates into the Imperial Army for years. It was also the day on which Count Lajos Batthyány (1807–1849), prime minister of the first independent Hungarian government, was executed in Pest-Buda, or present-day Budapest. He was a statesman of European standards and vision who, from the very beginning of his political career, had fought for the creation of a new, civic, and democratic state to replace feudal Hungary. The site of his execution became the site of the Batthyány sanctuary lamp erected in 1926 in the centre of Budapest, whose inauguration was also attended by the last living 1848 soldier.

Among the executed were counts and commoners, descendants of Croatian and Serbian border guard families, imperial Germans, and native Armenians. Some were connected to the Hungarian cause by family ties, others by their unit or simply by their wealth and social status. But all of them were men who believed that once they had sworn an oath to the Hungarian constitution at the behest of the emperor, they had to defend that constitution—even against the emperor himself. That is why they did not flee after the surrender, did not escape from Russian captivity, even though the Russians themselves had encouraged them to do so, and some even turned back from the border. They could have done so, since some of those who escaped would later go on to fight alongside Garibaldi in Italy, or even to achieve high ranks in the Turkish Empire, such as the Polish-born General Bem (Józef Zachariasz Bem), who became an Ottoman pasha under the name of Murad.

The fate of the executed demonstrates that 6 October is not only a tragedy for the leaders of the independent Hungarian army but also the leaders and participants of the Hungarian civic transformation. On this day, we can remember all the living martyrs, the military officers sentenced to prison, the members of parliament, and the conscripted soldiers. 6 October is also the day of those who were forced to emigrate and those who died in emigration, who were forced to change their country but could not change their hearts. 6 October is the day of remembrance of a great endeavour, the tragic end of the attempt to create an independent Hungary, and therefore not only of the martyrs but of the nation as a whole.

‘6 October is the day of remembrance of a great endeavour, the tragic end of the attempt to create an independent Hungary’

The central event of the Transylvanian commemorations is held every year, including in 2024, in Arad, which Lajos Kossuth himself named the ‘Hungarian Golgotha’. The first statue committee was set up here in 1867, the year of the Austro–Hungarian Compromise, and on 6 October 1890 the Statue of Liberty, the work of sculptor György Zala, was unveiled on Arad’s Liberty Square (now Avram Iancu Square). Although the statue was demolished in 1925, it was re-installed on a new site in 2004. The remains of eleven of the martyrs were laid to rest in a crypt at the Martyrs of Arad Memorial on 6 October 1974.

To this day, the National Museum of Freedom Fighters’ Memorabilia in Arad is one of the most important collections of the Revolution, which was established as a result of a national collection following an appeal in 1867. Opened in Arad in 1893, the museum’s collection includes personal belongings of the martyred generals of the Revolution and more than 17,000 objects and documents. In 2009 with EU funding, all the items in the collection were catalogued, digitized, and restored, and since October 2015 it has been on permanent display. Some of the artefacts are very special, such as the piece of wood that tradition has it came from the broom handle used by workers at a London brewery to beat the Austrian general Haynau, who had crushed the Hungarian Revolution, during his visit to the British capital.

Since Arad is outside the country’s borders, as is the birthplace or resting place of most of the martyred generals, the town of Gyula in Hungary, 70 kilometres away from Arad, took over its place. After the surrender at Világos (now Șiria, Romania) on 13 August 1849, when the Hungarian army laid down their arms in front of the Russian forces allied with the Austrians, the Russians gathered the officers, placed them in houses in the town today marked with memorial plaques, disarmed them on 22 August and then handed them over to the Imperial–Royal Army. The officers were ‘disarmed’ between the castle and the palace, near the present-day Martyrs of Arad Memorial, which was inaugurated on 6 October 1989 on the Remembrance Day of the Martyrs of Arad. In the centre of the memorial’s colonnade, the weapons stacked in a pile recall the tragic doomsday.

The 1848–49 Revolution and War of Independence had symbolic power even during the communist dictatorship. It was a reminder of sovereignty, of the struggle against oppression and invaders, as well as the memory of the defeated Revolution of 1956. Until 1867, the commemoration of the martyrs of Arad could only take place in secret, but after the Compromise, 6 October became a national day of mourning. Although it was not a public holiday, it was not banned during the communist period either—the martyrs were commemorated in schools and newspapers, however, the emphasis was on Austrian terror and the appreciation of the intervening Russian troops. Finally, after the regime change, the government declared it a national remembrance day in November 2001. On this day, traditionally, the national flag of Hungary is put at half-mast in Kossuth Square, black flags are displayed on public buildings, and a commemoration is held in schools.

Read our articles about 6 October from previous years: