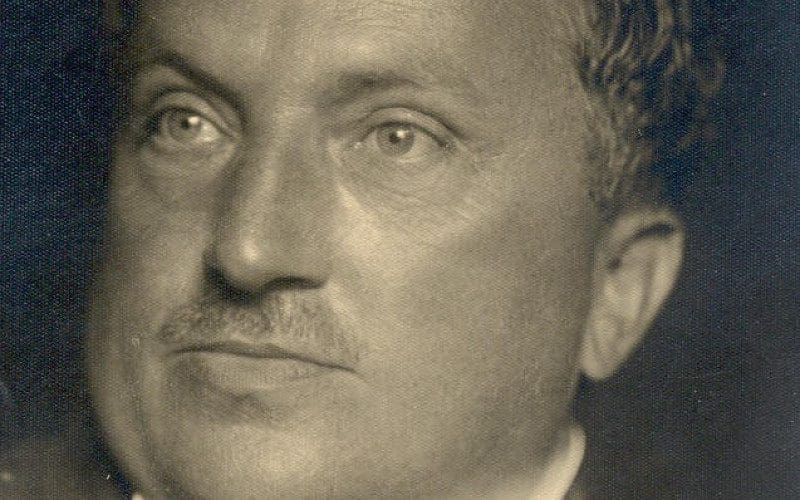

This article is the final, closing piece of our series on the nationalist writer Dezső Szabó. We have previously explored his relentless anti-capitalism and his contradictory views regarding Hungarian Jewry and anti-semitism. This final piece deals with his even more chaotic relationship to the contemporary governing right, and his rocky road from Liebling-author to opposition prophet during the twenties and the rest of the Horthy-era. Szabó himself announced his turn against the premiership of István Bethlen in 1923 as follows:

‘I was wrong, as were others of good faith […]The Jewish question is only one part of the problem of Hungarian democracy. The relation of feudal, clerical, commercial-industrial capitalism to the mass of workers, […] the institutionalization of the exploitation of labour: this is the universal problem. Once we implement this Hungarian democracy, once we make all exploitation impossible with our institutions: then the Jewish question and all racial questions will fall by themselves’.[i]

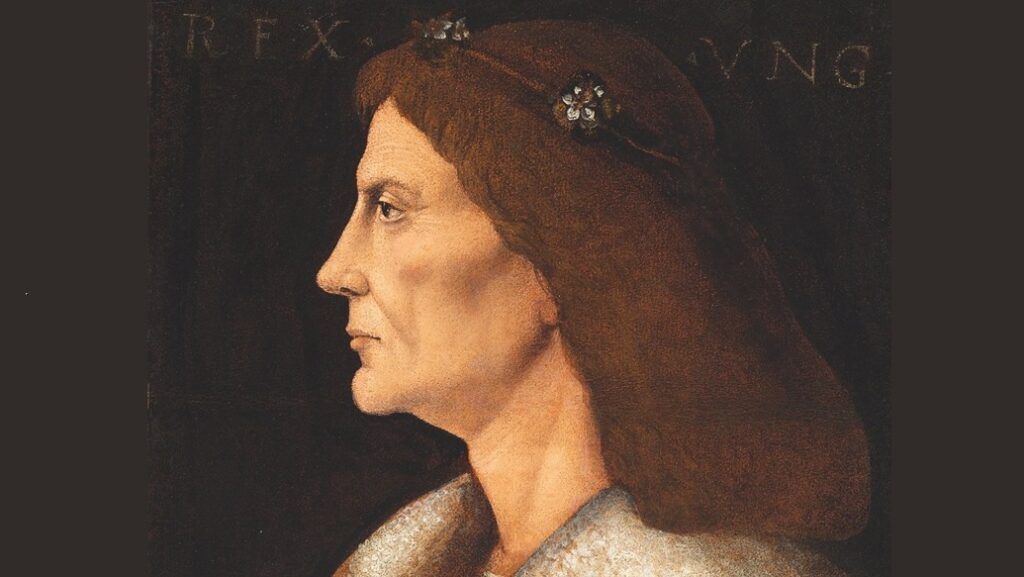

The consistency of his thinking is shown by the fact that he expressed the same in 1937, when he was convicted of anti-class agitation for a series of pamphlets stylishly named Mátyás Ludas (alluding to the tale of a boy of the same name who, in the story, punishes a corrupt lord by tying him to a tree and flogging him with a stick). In his article entitled ‘The System of Extremes’, in which he vindicated the material advantages of others for himself and his peers, he spoke about how ‘the respectable, the dignified, the gracious and the Jewish gentlemen’ drink champagne, drive cars, go to bars and wear jewellery, while ‘hundreds of thousands of the Hungarian peasantry live on meagre morsels, bereft of land […] they stagger in a breadless, blind life and toil on the land of the masters’.[ii]

The judgment based on the article correctly stated that Szabó’s piece, which envied the wealth of the rich and wanted to expropriate it, was suitable for inciting feelings, but missed the mark when it classified the article as anti-semitic. In this sense, Szabó was right, who defended himself as not considering the Jews but the rich as his enemies, regardless of religion: ‘In my writing I did not talk about the poor Jews, but about the rich bank managers and industrialists, the vast majority of whom have long been Catholics, Unitarians, Calvinists and Greek, so anything but Jewish’. ‘I always condemned anti-Semitism,’ he added, ‘however, I believe that the Jewish question cannot be silenced. During the long days, I did not group the streets of Budapest in such a way that their economic life was completely paralyzed during these Jewish holidays’, his words were recorded in court.[iii]

Szabó saw anti-Semitism as a distraction because of the ‘German threat’

Although his statement that he had not made any anti-semitic statements since the years of the ‘counter-revolution’ did not hold up, it is a fact that his anti-Jewish statements moderated since 1923 – although only at the expense of Hungarians of German origin. By that time, Szabó saw anti-Semitism as a distraction because of the ‘German threat’: Hungarian racialists scolded the Jews, while the real opponent had long been the Germans. The Hungarian, ‘running from Jewish imperialism’, jumped into the Danube, and the raciaists ‘threw a couple of German wursts and a glass of Bavarian beer to the drowning man’, so raged Szabó.[iv] He amply titled one of his pamphlets Hungarianism [the ideology of the Arrow Cross – ed.] and death. The pamphlet likened pro-Nazi views to the death of the Hungarian nation.[v] Following this line of thought, in his paper titled ‘The Critique of Anti-Judaism’, published in 1938 in response to the first anti-Jewish law, he already described anti-Semitism as ‘the roar of the street, the campaign of pirates and sewer gladiators’, which diverts attention from the much more dangerous German ‘invaders’. Hating Germans instead of Jews is by no means a better solution, although it is true that Szabó’s anti-German thought was coupled with strong anti-Nazi and anti-Arrow Cross sentiments. In his pamphlet, he called the persecution of Jews ‘the murderous plan of an irredeemable scoundrel’ and the numerus clausus law the loss of Hungarian minds. His words could have been more persuasive if he had added that he was one of the biggest supporters of the numerus clausus law 18 years earlier.[vi]

Despite the above, he also confronted anti-Semitism in other public speeches. At the end of his reading night in Pécs in 1927, one man said the following: ‘I am emptying my glass to Greater Hungary, excluding all unworthy Jewish folks.’ Dezső Szabó immediately attacked him: ‘Young man, I will not allow you to say such things at my table. Watch your tone next time!’, the Jewish press reported.[vii] And he told a Jewish journalist in 1934 that

‘I found the most beautiful, harmonious and intimate family life in Judaism. The Jew brings the faith and thinking of his entire kind into his family life […] And how they teach each other, father and child, child and father! Wonderful! The way a father puts Jewish writing, the book, a tool of Jewish culture, into the hands of a small child and teaches him to appreciate and respect its writers and poets, it cannot be found anywhere, anywhere I say. In this way, it will then be possible for the Jewish young man to absorb knowledge and intelligence together with his mother’s milk, so to speak.’[viii]

It is perhaps not surprising that one of his final novels, the Strangulated Rooster, was a strongly anti-Nazi work, written against the increasing of violence in society.[ix] The legend was also spread in newspapers in 1945 that in his final days during the siege of Budapest, Szabó sheltered a Jewish neighbour in his flat,[x] but this has not been confirmed elsewhere.

Szabó was clearly anything but a pro-Nazi

Much of this has been lost, since the historians of later decades interpreted Szabó’s writings as something akin to Nazims or the ideology of the Arrow Cross. Szabó was clearly anything but a pro-Nazi, in fact, he was opposed to Nazism and the Arrow Cross during his entire career. This does not negate his anti-semitism or his violent articles and speeches in the early twenties, but the broad picture seems to be a complicated one, that of an unruly, untamed champion of ordinary Hungarian people, and not of a pro-capitalist, pro-fascists right-wing author. Szabó, with all his merits and mistakes, deserves the objective attention of contemporary historians.

[i] Dezső Szabó, ’Rocambol-romantika’, Az egész látóhatár Vol. 1 (Budapest: Püski, 1991), 494–495.

[ii] Dezső Szabó, A szélsőségek rendszere, (Budapest: Ludas Mátyás különlenyomat, 1937), 6.

[iii] Népszava, 9 Oct. 1937.; Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum, V.4518/4/32.

[iv] Dezső Szabó, ’A magyar problémák egysége II.’ Előőrs, 24 March 1928.

[v] Dezső Szabó , ’Hungárizmus és halál’, (Ludas Mátyás füzetek 42. 1938)

[vi] Dezső Szabó, ’Az antijúdaizmus bírálata’ in Géza Komoróczy, ed, Zsidók a magyar társadalomban. Írások az együttélésről, a feszültségről és az értékekről, 1790-2012, vol. II. (Pozsony: Kalligram, 2015), 117, 119, 129.

[vii] Egyenlőség, 5th Nov. 1927.

[viii] Egyenlőség, 28th March 1934.

[ix] Dezső Szabó, ’A megfojtott kakas’ in Dezső Szabó Levelek Kolozsvárra (Keresztes Kiadás,1943).

[x] MTA Kézirattár, Ms 2566/74.