European and Hungarian Jewry under Attack from Anti-Semitism of the Left, the Far Right, and Islamists

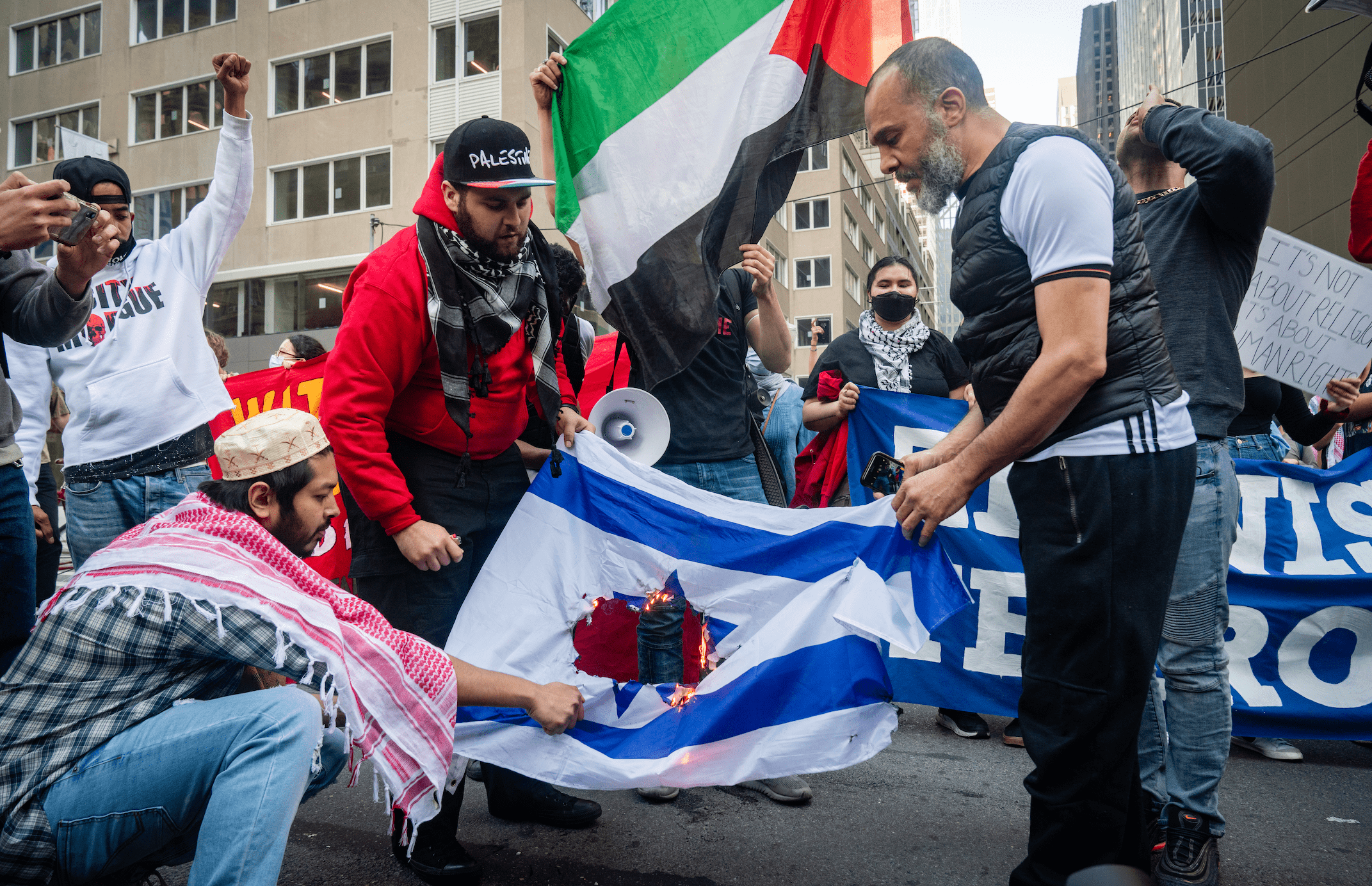

In May 2021, Europe was shocked by the news, relayed on television, news portals, and newspaper articles, that Jews were being attacked in major cities, and that anti-Semitic mass demonstrations were being held in Berlin, Amsterdam, London, and Paris, while certain groups were explicitly calling for physical violence against Jews. Following the Israeli–Palestinian conflict of May 2021, when the terrorist organization Hamas launched thousands of rockets aimed at Israel, triggering strong Israeli counterattacks, a wave of anti-Semitic atrocities targeted Jewish communities in Western and Northern Europe, as well as North America. But how was it possible for the situation of Jews in the Western world to deteriorate to such an extent that one Jewish media outlet senses a return to the anti-Semitism of the 1930s? And what has been the reaction of the international left?

The Migration Crisis

The migration crisis which hit Europe in 2015 inspired critical social, economic, and political discourse on a number of issues relating to the phenomenon of illegal mass immigration, with the issue of anti-Semitism as one crucial aspect. In the German mainstream media, the following headlines appeared as early as 2015: ‘More Anti-Semitism Brought to Germany by Refugees?’ (Süddeutsche Zeitung), ‘What About the Consequences of Refugees’ Anti-Semitism?’ (Die Welt), ‘Refugees’ Anti- Semitism Raises Concerns’ (Tagesspiegel), ‘Imported Anti-Semitism’ (Spiegel Online).2

Similar examples can also be cited from the political sphere. In November 2016, for instance, Erika Steinbach, a CDU representative in the Bundestag, commented on anti-Semitism in Arab countries on social media, claiming that ‘we would have an additional one million anti-Semites within a year’.3 In an interview given in 2018, Armin Laschet of the Christian Democrats, then Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia, identified the 2015 migration crisis as one of the causes of growing anti-Semitism.4 Even the avowedly liberal New York Times admitted in an article published in the spring of 2019 that ‘a number of surveys show that Muslims in Germany and other European countries are more likely to hold anti-Semitic views than the overall population’.5

According to Shimon Lasker, an orthodox rabbi in Brussels, mass immigration is ‘naturally’ connected with increasing anti-Semitism

Such critical discourse has also found its way into Jewish communities in Western Europe. When interviewed by the author in 2017, Raphael Evers, former chief rabbi of Rotterdam and Düsseldorf, pointed out that he had experienced anti-Semitism in the Netherlands from ‘people of Middle Eastern background’.6 According to Shimon Lasker, an orthodox rabbi in Brussels, mass immigration is ‘naturally’ connected with increasing anti-Semitism.7 The sociologist David Pinto, lecturing at the University of Amsterdam, highlighted during the same interview that ‘there is anti- Semitism—now a lot more than ever before. Mostly Moroccan Muslim youth are responsible for it.’8 In 2018, the largest German-Jewish umbrella organization, the Central Council of Jews in Germany, proposed an educational programme for immigrants arriving from Muslim countries to prevent anti-Semitism. According to Abraham Lehrer, the vice president of the organization, ‘many people [arriving from Muslim countries] were influenced by regimes where anti-Semitism is part of the philosophy of the state’. In order to prevent such people from ‘subsequently openly expressing their views’ in Germany, Lehrer proposed ‘integration courses’ organized for them.9

Jewish leaders’ concerns have been verified, to a certain extent, by a growing body of published research. A German study in 2017 admitted in its introduction that ‘well-founded results of surveys of anti-Semitism among refugees were not yet available’.10 A few memorable affairs, however, stirred considerable media interest. A Palestinian migrant girl, with whom German Chancellor Angela Merkel had appeared together in public in 2015, argued for the abolition of the Israeli state shortly thereafter.11 Basil Harara, a Palestinian migrant who arrived in Hungary, also provoked loud protests in the Hungarian Jewish press when he recited anti-Semitic poetry at a pro-migration event organized by the left.12 In December 2017, a Syrian migrant attacked a kosher restaurant in Amsterdam with sticks.13

Anti-Semitic Attacks

If we review the available data—collected by state bodies and civil organizations— concerning the reports of anti-Semitic atrocities in Western and Northern European countries strongly affected by mass immigration, an increasing trend in the number of attacks and an overrepresentation of perpetrators with a migrant background can be ascertained.

Based on the data above, it can be stated of those countries where complete data sets are available, that the number of incidents of an anti-Semitic nature continuously increased in the UK, Germany, and Denmark from the beginning of the 2015 migrant crisis up to 2018, and continued to grow in the UK in 2019. Similarly, an increase was observed in all three countries at the time of the Gaza conflict in 2014, followed by a decrease in 2015. Subsequently, however, the number of anti-Semitic incidents started to increase again in the UK, Germany, and Denmark (showing a variance of a few dozens in 2016 and 2017), and although in the Netherlands a decrease was recorded in 2016, the number of attacks then started to increase again, with extremely violent incidents in 2017 (stabbings and scuffles in city centres). In the Netherlands, the number of incidents recorded in 2019 even exceeded those from 2014. In the case of France, the decrease was continuous until 2018, when the number of incidents showed a dramatic increase. In Sweden, after a drop in 2016, the numbers in the years 2017–2018 once again reached the high level recorded in 2015, as can be seen in the combined data on atrocities reported during those two years. In Italy, numbers did not show a significant variance in 2014 and 2015, but a major increase was recorded in 2016, followed by stagnation in 2017, and a steep increase of the number of attacks over the last two years. For Norway, there is insufficient data for analysis. The only lethal atrocity outside France was recorded in Denmark in 2015. Naturally, we have every reason to believe that in certain countries, including the UK, Germany, France, and the Netherlands, the number of atrocities was in reality significantly higher than the number reported.18 Following the COVID pandemic of 2020, the number of anti-Semitic atrocities increased only in Germany, while a slight overall decrease was registered in other countries.

It still remains to be clarified whether persons with a migrant background are to be held responsible for the atrocities cited above. In the case of the countries referred to above, the 2018 data provided by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) can be taken into consideration as the baseline; the agency explored, by conducting surveys among local Jewish communities, the extent to which immigrants were represented among anti-Semitic assailants. It is important to note that the numbers below were reported by the members of the communities themselves and were not presented as official statistical data.

The data above demonstrate that in almost all cases the majority of assailants were identified as Muslim by the Jewish victims interviewed (except in the UK and Italy). It should also be noted that according to the victims, right-wing assailants were outnumbered by radical leftist assailants in most of the countries examined (with the exception of Germany), and in Italy it was in fact the latter group to which the majority of the assailants were assumed to belong. It should be added that German statistics have been strongly criticized. German police interpret almost all attacks against Jews as being of rightist motivation, while they fail to record some of the attacks motivated by anti-Israel sentiments as anti-Semitic, putting them under a separate heading of ‘Anti-Israel’ acts.20 Strangely enough, a survey conducted by German police also put the attempted arson against a synagogue in Germany into the latter category.21 A similar problem of methodology is raised by a 2018 German–British state-funded survey of the five countries, which also applied a clear-cut differentiation between acts motivated by anti-Israel sentiments and anti-Semitism.22 The latest FRA dataset covering the period up to 2019, however, does not include any references to the background of the assailants.23 Moreover, unfortunately, data series that do specify the background of individual perpetrators usually fail to indicate whether those with a migrant background are ‘nth-generation’ migrants or those who have recently arrived in Europe.

German police interpret almost all attacks against Jews as being of rightist motivation

A Stab in the Back: Reactions on the Left

Reactions of the left to the above phenomena should be understood in the light of what has been claimed by Rafaela Dancygier, a political scientist at Princeton University: ‘In London, Brussels, and Rotterdam, electoral contests are frequently won by candidates leaning on clan leaders and imams who can turn out their followers.’24 According to a British electoral survey, between 2002 and 2010 the Labour Party nominated Muslim candidates in a clearly targeted manner in areas where the proportion of Muslim voters among the electorate was particularly high.25 Based on data collected by the British Religion in Numbers (BRIN) project of the University of Manchester, 85 per cent of Muslims voted Labour at the 2017 parliamentary elections.26 Based on BRIN data, corroborated by other researchers, the same tendency was also observable between 2005 and 2015.27

And while in May 2021 Jews in Britain were repeatedly attacked in the streets in the immediate aftermath of the Gaza conflict, the international left took a unified stance against Israel. While national governments, such as that of Hungary, stood up for Israel’s right of self-defence, Jeremy Corbyn, the former head of the Labour Party—declared the most anti-Semitic public figure of the year by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre in 2019—posted on Twitter that ‘the escalation of hostilities overnight in Jerusalem & now Tel Aviv is a direct result of the home invasions [in] Sheik Jarrah by government-backed settlers. If it wanted, Israel could halt the bloodshed by ending the siege of Gaza and the occupation of Palestine. Ceasefire needed now.’28 All this is rather ironic, as Corbyn accused the Hungarian government in 2018, for instance, of ‘rubbing up against anti-Semitism’.

Labour MP Zarah Sultana, who recently said Hungary was anti-Semitic, made similar declarations. She posted that ‘today, outside Downing Street, we showed that the Palestinian people will never be alone in their struggle for justice. We stand in solidarity, today and always.’29 She attached the hashtags ‘save Sheikh Jarrah’ and ‘free Palestine’ to her message. Keir Starmer, the new Labour leader, whose wife is Jewish, tried to post a balancing message on Twitter, but he blamed both Israel and Hamas—a democracy and a terrorist organization, respectively—for the conflict. Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson condemned violence in his Twitter messages addressed to both sides, but he also spoke out recently against anti-Semitic demonstrations in the streets of London.30

Hungarian readers should not overlook phenomena which suggest that the left in Hungary may also move in this direction soon. It should be remembered that Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Péter Szijjártó objected to the ‘one-sided’ statements of the EU regarding Israel while his European colleagues called for a ceasefire between Israel and the Palestinians. Szijjártó’s quote was shared by Anett Bősz—president of the Hungarian Liberal Party and a member of the Democratic Coalition’s (DK) caucus in Parliament—on her social media page, with the comment that ‘now it was just nauseating’. Tímea Szabó, co-chairing the Párbeszéd (Dialogue) party with the mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony, made a similar statement, claiming that Szijjártó had made a ‘historical mistake’ and that ‘the inhuman side of Viktor Orbán assumes a new shape each day’. Karácsony, by the way, selected Dávid Dorosz, a former LMP politician and now a nominee of MSZP (Hungarian Socialist Party) and Párbeszéd, for the post of vice mayor of Budapest, at the opposition primary in one of the electoral districts of Pest County. In his book published in 2019, Az idő szorításában (Under the Pressure of Time), Dorosz wrote: ‘Today, problems may emerge due to the Iranian–Saudi scramble on multiple fronts, featuring a number of proxy wars, and the illiberal government of Israel.’ Dorosz is currently the campaign manager of Párbeszéd.

Compared with the above, the interview with Jobbik MP Koloman Brenner sounds moderate: he said the opposition should adopt the EU’s position in the conflict (that is, it should also condemn both sides). The reactions of the Hungarian opposition have represented a shift from their earlier position of ‘let’s not say anything about anything, we will sort out everything after the elections’; the left has started to direct criticism against Israel in Hungary as well.31

A New Low: Péter Márky-Zay, the Opposition’s Anti-Semitic Prime Ministerial Candidate

The new ray of hope for the opponents of the conservative Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is Péter Márki-Zay, the mayor of the southern Hungarian town of Hódmezővásárhely and a Catholic father of seven. Márki-Zay became known nationwide when in 2018 he was elected mayor of his hometown, previously considered a stronghold of the ruling Fidesz party.

Since the Hungarian opposition has formed an alliance32 to run together against Orbán, Márki-Zay, who won the opposition primaries in October 2021 with 56 per cent of the votes, will likely be Orbán’s only opponent in the upcoming April 2022 elections. An unlikely candidate, as he is known for his strongly conservative views—but perhaps the Hungarian left thinks that you need to fight fire with fire. (This article was drafted and published in the print edition before the elections – the editor.)

Márki-Zay suggested that the Hungarian Guard (Magyar Gárda) be resurrected

But what are this staunchly right-wing politician’s views on Hungarian Jews and other minorities? His record on minority-related issues is, in fact, by no means spotless. In September 2018, Márki-Zay had his picture taken together with Tamás Sneider, then president of Jobbik, a former skinhead known for having performed Nazi salutes at his own wedding, and who confessed33 to beating a Roma person in 1992 in an allegedly racist attack. Márki-Zay was shaking Sneider’s hand in the photograph, and also delivered a controversial speech34 in which he suggested that the Hungarian Guard (Magyar Gárda) be resurrected. The Hungarian Guard was a far-right formation banned by the Hungarian government.

It is worth noting that Márki-Zay’s political movement, the Movement for Everybody’s Hungary (Mindenki Magyarországa Mozgalom) previously supported35 outright neo-Nazi politicians from the party Jobbik, such as Lajos Rig, an MP who at one point called Romani people ‘the biological weapons’ Jews used to exterminate Hungarians. Márki-Zay has also personally supported36 László Bíró, a Jobbik politician who referred to Jews as ‘flea slides’ and called Budapest ‘Judapest’.

When the so-called Pegasus scandal broke in July 2021—the gist of which is that a number of Hungarian journalists were allegedly spied upon with Israeli technology— Márki-Zay attacked37 the Orbán government in a Facebook post showing Orbán standing in front of the Israeli flag and a Menorah. While the Star of David was partially blocked from view, the Menorah was clearly visible. The message was obvious: the Jews, allied with Orbán, are spying on the Hungarian people.

In October 2021, it was revealed38 that Márki-Zay’s campaign was supported by the World Alliance of Szeklers (Székelyek Világszövetsége), a far-right organization headed by Barna Csibi. Csibi had previously installed a poster in the Transylvanian town of Csíkszereda stating that ‘you should be ashamed of yourself if you have ever made a purchase in a Jewish shop’. One month later, Márki-Zay gave an interview to the BBC, in which he suggested that Jews should vote for the neo-Nazi Jobbik party ‘with good heart’.39

The data and quotations presented herein leave the objective observer in little doubt: the international and domestic left is increasingly turning against Jews and Israel, finding new allies among the anti-Semitic members of the immigrant masses, and also forming an alliance with the old type of far-right anti- Semites.

NOTES

1 For this study, the author used parts of his article currently under editing for publication by the Migration Research Institute and MCC Press, earlier published in the online version of Mandiner. Regarding the latter, see the relevant footnotes.

2 Headlines quoted in Sina Arnold and Jana König, Flucht und Antisemitismus (Berlin: Berliner Institut für empirische Integrations- und Migrationsforschung, 2017), 6.

3 https://twitter.com/SteinbachErika/ status/802212279945142272?lang=de, accessed 15 September 2021.

4 Ofer Aderet, ‘Anti-Semitism Is Growing among Far Right and Muslim Migrants in Germany, State Premier Tells Haaretz’, Haaretz (3 September 2018), www.haaretz.com/worldnews/europe/.premium-anti- semitism-growing-in-germany-state-premier-tells- haaretz-1.6436155, accessed 4 November 2019.

5 James Angelos, ‘The New German Anti-Semitism’, The New York Times (21 May 2019), www.nytimes. com/2019/05/21/magazine/anti-semitism-germany. html, accessed 15 September 2021.

6 László Bernát Veszprémy, ‘Ha kikapcsolod a mikrofont, mesélek’ (Turn Off the Mike, and I Will Tell You), Szombat (30 May 2017), www.szombat. org/politika/ha-kikapcsolod-a-mikrofont-meselek- antiszemitizmus-hollandiaban, accessed 15 September 2021.

7 László Bernát Veszprémy, ‘“A bevándorlók lángba borítják az országot” – Shimon Lasker brüsszeli rabbi a Mandinernek’ (‘Immigrants Set Country Ablaze’. Shimon Lasker, Brussels Rabbi, Talks to Mandiner), Mandiner (30 December 2017), https://mandiner.hu/cikk/20171228_veszpremy_laszlo_bernat_a_bevandorlok_langba_boritjak_az_orszagot_shimon_ lasker_brusszeli_rabbi_a_Mandinernek, accessed 15 September 2021.

8 Veszprémy, ‘Ha kikapcsolod …’.

9 ‘German Jews Propose Anti-Semitism Lessons for Muslim Migrants’, BBC (5 November 2018), www. bbc.com/news/world-europe-46095808, accessed 15 September 2021.

10 Sina Arnold and Jana König, Flucht und Antisemitismus, 5.

11 Benjamin Weinthal, ‘Palestinian Girl Whom Merkel Caused to Cry Wants to Abolish Israel’, The Jerusalem Post (28 July 2015), www.jpost.com/Arab-Israeli-Conflict/Palestinian-girl-whom-Merkel-caused-to- cry-wants-to-abolish-Israel-410383, accessed 15 September 2021.

12 László Bernát Veszprémy, ‘Progresszív korholás és machiavellista szép szavak’ (Progressive Scolding and Machiavellian Sweet Talk), Szombat (7 February 2017), www.szombat.org/velemeny/progressziv-korholas-es- machiavellista-szep-szavak, accessed 15 September 2021.

13 László Bernát Veszprémy: ‘Ha nem akarsz bajt, ne viselj kipát. Hollandiában járt a Mandiner’ (If You Want No Trouble, Do Not Wear a Yarmulke), Mandiner (8 May 2019), https://mandiner.hu/ cikk/20190508_hollandia_riport, accessed 15 September 2021.

14 Combined with 2014 data, cf. László Bernát Veszprémy, Bevándorlás és antiszemita indíttatású atrocitások. nyugat- és észak-európai körkép (Immigration and Anti-Semitic Atrocities. A Western and Northern European Overview), Migrációkutató Intézet (Institute of Migration Research), 15

January 2019, www.migraciokutato.hu/2019/01/15/ bevandorlas-es-antiszemita-indittatasu-atrocitasok- nyugat-es-eszak-europai-korkep/, accessed 15 September 2021.

15 Four Jews (Philippe Braham, Yohan Cohen, Yoav Hattab, and François-Michel Saada) were killed by Muslim perpetrators in January 2015 in a kosher shop in Paris; Sarah Halimi, a Jewish woman in Paris, was thrown out of the window of her apartment by a Muslim assailant in April 2017. Mireille Knoll, another French Jewish woman—a Holocaust survivor—was murdered in March 2018.

16 The synagogue of Halle suffered a murderous far-right attack in October 2019, in the course of which two non-Jewish persons were killed by the perpetrator.

17 Dan Uzan, a Jewish security guard, was shot dead in a synagogue in Copenhagen by a Muslim assailant in February 2015. ‘Denmark Killings: Funeral for Jewish Synagogue Guard’, BBC (18 February 2015), www. bbc.com/news/world-europe-31525121, accessed 15 September 2021.

18 The CST measuring the atrocities in England processed fewer incidents than what was reported

to it; researchers in Germany and alternative Jewish organizations in France have claimed that official data should be approached with reservations; the staff of CIDI, a Jewish organization in the Netherlands, believe that Jews have become ‘weary’ of reporting incidents.

19 FRA, ‘Experiences and Perceptions of Antisemitism – Second Survey on Discrimination and Hate Crime against Jews in the EU (2018)’, https://fra.europa.eu/ en/publication/2018/experiences-and-perceptions- antisemitism-second-survey-discrimination-and-hate, accessed 15 September 2021.

20 Cnaan Lipshiz, ‘Germany Is Accused of Downplaying Anti-Semitic Attacks by Muslims’, JTA (14 June 2019), www.jta.org/2019/06/14/global/germany-is-accused- of-downplaying-anti-semitic-attacks-by-muslims, accessed 11 November 2019; Johannes Due Enstad, Antisemitic Violence in Europe, 2005–2015. Exposure and Perpetrators in France, UK, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Russia (Oslo: University of Oslo, 2017), 19.

21 Enstad, Antisemitic Violence, 19.

22 For this problem of methodology, see Enstad, Antisemitic Violence, 18–19. For criticism of the 2018 survey conducted by the University of London–EVZ, see Andrew Baker, ‘A Recent Study into Rising Antisemitism in Europe Ignores the Role of Muslim Migrants’, www.thejc.com/comment/comment/recent- study-into-rising-antisemitism-in-europe-ignores-the- role-of-muslim-migrants-andrew-baker-ajc-1.464720, accessed 15 September 2021.

23 https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2020/ antisemitism-overview-2009-2019.

24 Rafaela Dancygier, ‘Muslim Voters and the European Left’, Foreign Affairs (6 February 2018), www. foreignaffairs.com/articles/europe/2018-02-06/muslim- voters-and-european-left, accessed 15 September 2021.

25 Rafaela Dancygier, ‘The Left and Minority Representation: The Labour Party, Muslim Candidates, and Inclusion Tradeoffs’, Comparative Politics (October 2013), 1–21.

26 Ben Clements, ‘Religious Affiliation and Party Choice at the 2017 General Election’, BRIN (11 August 2017), www.brin.ac.uk/religious-affiliation-and-party-choice- at-the-2017-general-election/, accessed 15 September 2021.

27 Clements, ‘Religious Affiliation …’; Dilwar Hussain, ‘Muslim Political Participation in Britain and the Europeanisation of Fiqh’, Die Welt des Islams, 44/3 (2004), 376–401, 390.

28 https://twitter.com/jeremycorbyn/ status/1392434910321905668, accessed 15 September 2021.

29 https://twitter.com/zarahsultana/ status/1392232205871689728, accessed 15 September 2021.

30 See also László Bernát Veszprémy, ‘Így fordult a nemzetközi baloldal Izrael ellen’ (This Was How the International Left Turned against Israel), Mandiner (20 May 2021), https://mandiner.hu/cikk/20210520_ baloldal_izrael, accessed 15 September 2021.

31 Veszprémy, ‘Így fordult …’.

32 https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/a-deal-with-the-devil- how-the-hungarian-left-embraced-neo-nazi-jobbik/, accessed 28 January 2022.

33 www.jta.org/2019/08/12/global/in-hungary-some- left-wing-jews-are-ready-to-work-with-a-far-right- party-led-by-an-ex-skinhead, accessed 28 January 2022.

34 www.origo.hu/itthon/20181008-lazar-uzenetet- kuldott-markizaynak.html, accessed 28 January 2022.

35 www.facebook.com/773120112778785/photos/a.7731 35212777275/4104553332968763/?type=3.

36 https://fuhu.hu/marki-zay-felreerti/, accessed 28 January 2022.

37 www.facebook.com/321422908590395/photos/a.33 6272557105430/945124162886930/?type=3, accessed 28 January 2022.

38 https://mandiner.hu/cikk/20211031_antiszemita_ politikussal_allt_ossze_erdelyben_marki_zay, accessed 28 January 2022.

39 https://index.hu/kulfold/2021/11/24/marki-zay- peter-bbc-interju-korrupcio-europai-unio-valasztasok/, accessed 28 January 2022.