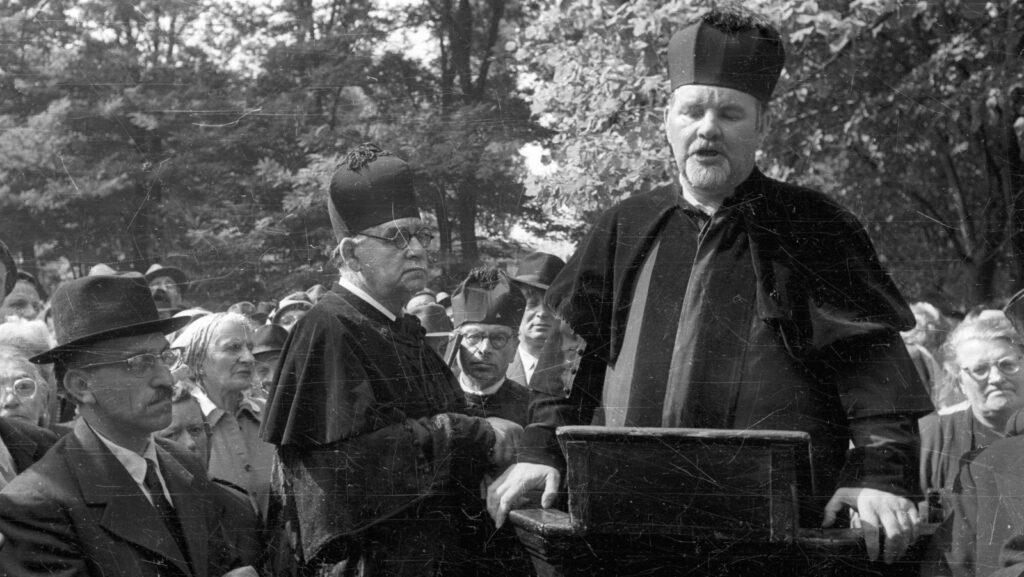

Ottokár Prohászka, Catholic Bishop of Székesfehérvár (1905-1927), was a deep, fascinating, original, but most of all, divisive author. His work has always been surrounded in controversy. Because of his groundbreaking social teachings, the early part of his career was mired in conservative criticism; because of his subsequent sharp right-wing turn, the latter part of his career was tarnished with accusations of antisemitism. Even after his death, his work has been the source of numerous debates among historians and politicians. In fact, Deputy Prime Minister Zsolt Semjén had to defend Prohászka in 2012 thus: ‘Ottokár Prohászka was not only the culmination of Hungarian social thinking, but also the founder of it. The charge of antisemitism used against him in the present is absurd because he died in 1927. It is unhistorical and unjust to hold him accountable for what happened in the 1930s or later, in the 1940s. […] Prohászka did not at all establish the ideology of Hungarianism [Ideology of the Arrow Cross, the Hungarian Nazi party – Ed.). These Nazi ideologies have always been neo-pagan, anti-Christian movements. Prohászka established a Christian-social mindset. […]’[1]

Politicians need not have a deep understanding of every 20th century Hungarian thinker, but if we interpret “the charge of antisemitism” as a charge saying that Prohászka was somehow an enthusiastic supporter of the anti-Jewish Nazi policy, Semjén was on point. Prohászka was certainly a leading social thinker of the Hungarian right, but this has largely been forgotten. In fact, Socialist historiography, which has largely dominated Hungarian public life before the 1989 democratic transition, labelled Prohászka a “capitalist” and a “lord” who found joy in the suffering of the common folk.[2]

This charge was wrong on many levels. Prohászka was from a modest family with no ties to the nobility, in fact, his maternal grandfather was a common baker. He was famous for his simple lifestyle even as a bishop: when he first took his seat at the episcopate, he did not get a coach but instead chose to walk. His diaries are full of his concern for poor people, and often include remarks on how many products or wares he bought from humble street vendors.[3] In one of the few surviving footages of the bishop, he can be seen purchasing a newspaper from an old lady on the street – perhaps a telling moment from the life of a bishop, who could have enjoyed a newspaper from the comfort of his palace.[4]

Prohászka greatly abhorred the lack of social policy in contemporary Hungary and was a loud supporter of granting more benefits to the poor

Prohászka greatly abhorred the lack of social policy in contemporary Hungary and was a loud supporter of granting more benefits to the poor. This can be seen even in his early writings. In 1894 he published “What is the Social Question?” and “The Role of the Priesthood Around the Social Question”. In “What is the Social Issue,” he explained his criticism of capitalism: while the idea of freedom was noble and was ingrained in the human soul, in economics terms, if unchained, it would lead to wild, vile, predatory money-hoarding. He therefore advocated a controlled economy where control was based on the “truths of Christ”.[5

In some of his writings he went ever further, arguing for the legitimacy of “class war” and declaring a “war” on big banks.[6] No one on the right quoted Marx as often and gleefully as Prohászka, who often incorporated Marx’s anti-Jewish remarks into his articles and speeches. Statements like this might help us understand why conservatives were wary of supporting Prohászka early on. In fact, between 1901 and 1916, numerous lauding articles can be found in the progressive Jewish press about Prohászka.[7]Perhaps they did not yet see the later confrontation with the bishop. Later, sadly, the bishop equated “Jewry” with communism, and his subsequent writings on this matter leave much to be desired.

The idea of social progress can also be found in his antisemitic writings as well. “We perceive antisemitism not as a racial, religious but as a social, business reaction” – he wrote in an anonymous article in 1893. This is not to justify his antisemitism or to find excuses for it, but to explain that his antisemitism was not a racial idea in his mind, but rather an economic reaction of the poor Hungarian people against capitalism – the latter he saw as a markedly “Jewish” phenomenon. After the right-wing counter-revolution of the years 1919-1921, Prohászka was disappointed with the return of the previous capitalistic system. ‘Did we want something conservative, reactionary, have we advertised a policy against the common people? Not in the slightest! We oppose the old Hungary, capitalist liberalism and feudalism, as well as the revolutionary face of Jewish radicalism or Marxist social democracy’, he explained to a friend.[8]

Prohászka has managed to preserve his image as a socially sensitive Catholic bishop while gaining good points with the postwar right-wing system

Interestingly enough, Prohászka has managed to preserve his image as a socially sensitive Catholic bishop while gaining good points with the postwar right-wing system. In fact, one rightist newspaper in the city of Székesfehérvár – where he was the bishop at the time – referred to him as “a true apostle of Socialism”.[9] This was already in 1920, one year after the fall of the short-lived communist Republic of Councils. Perhaps it did not hurt that after his death in 1927, many of his harsh comments about contemporary society were removed from the published edition of his diaries. These concerned his early support for the left-wing periods of 1918 and 1919, but also his criticism of the prevalence of prostitution in Hungarian society.

In summary, we can see Prohászka as a fascinating yet divisive author whose works are still being debated today. Much of the criticism directed against him have, however, missed their mark, as they failed to see the bishop’s true motivation behind his works – which were volatile and undiplomatic, but certainly patriotic and conservative, and of deep thought and excellent rhetoric. Prohászka was an original Hungarian Catholic social thinker who deserves to be judged on the whole of his career and all of his texts, like all other historical personalities.

[1] ‘Ez maga a történelem’, Népszabadság (17th August 2012), 6.

[2] See a collection of articles in the possession of the Archives of the Szociális Missziótársulat.

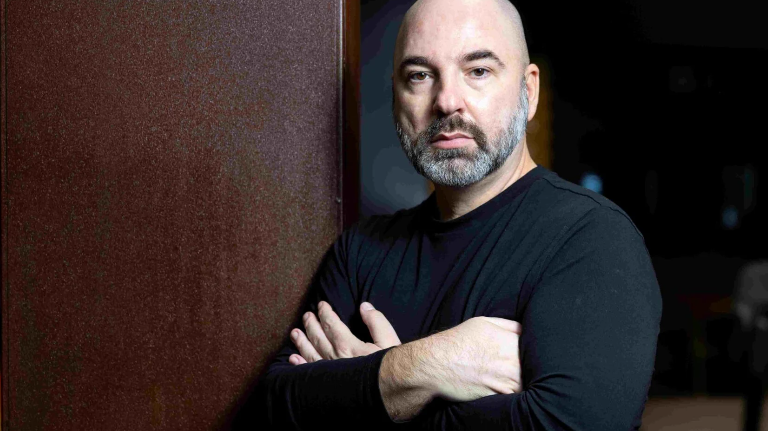

[3] László Bernát Veszprémy, ‘1921. A Horthy-rendszer megszilárdulásának története’, Bp., Jaffa (2021), 100.

[4] https://filmhiradokonline.hu/watch.php?id=5400

[5] http://www.ppek.hu/konyvek/Pap_Sandor_Prohaszka_Ottokar_szocialis_es_foldreform_elkepzelesei_1.pdf

[6] ‘Prohászka Ottokár a politika és kultúra főkérdéseiről’, A Nép (15th October 1922), 1-2.

[7] Veszprémy, ‘”Ha én zsidó lennék, cionista lennék.” Prohászka Ottokár és a keresztény cionizmus kérdései’, Egyháztörténeti Szemle, (2017), https://www.uni-miskolc.hu/~egyhtort/cikkek/veszpremylaszlo.pdf

[8] Veszprémy (1921), Op. cit, 29

[9] ‘Szocializmus kell, Testvér’ (1920), 1.