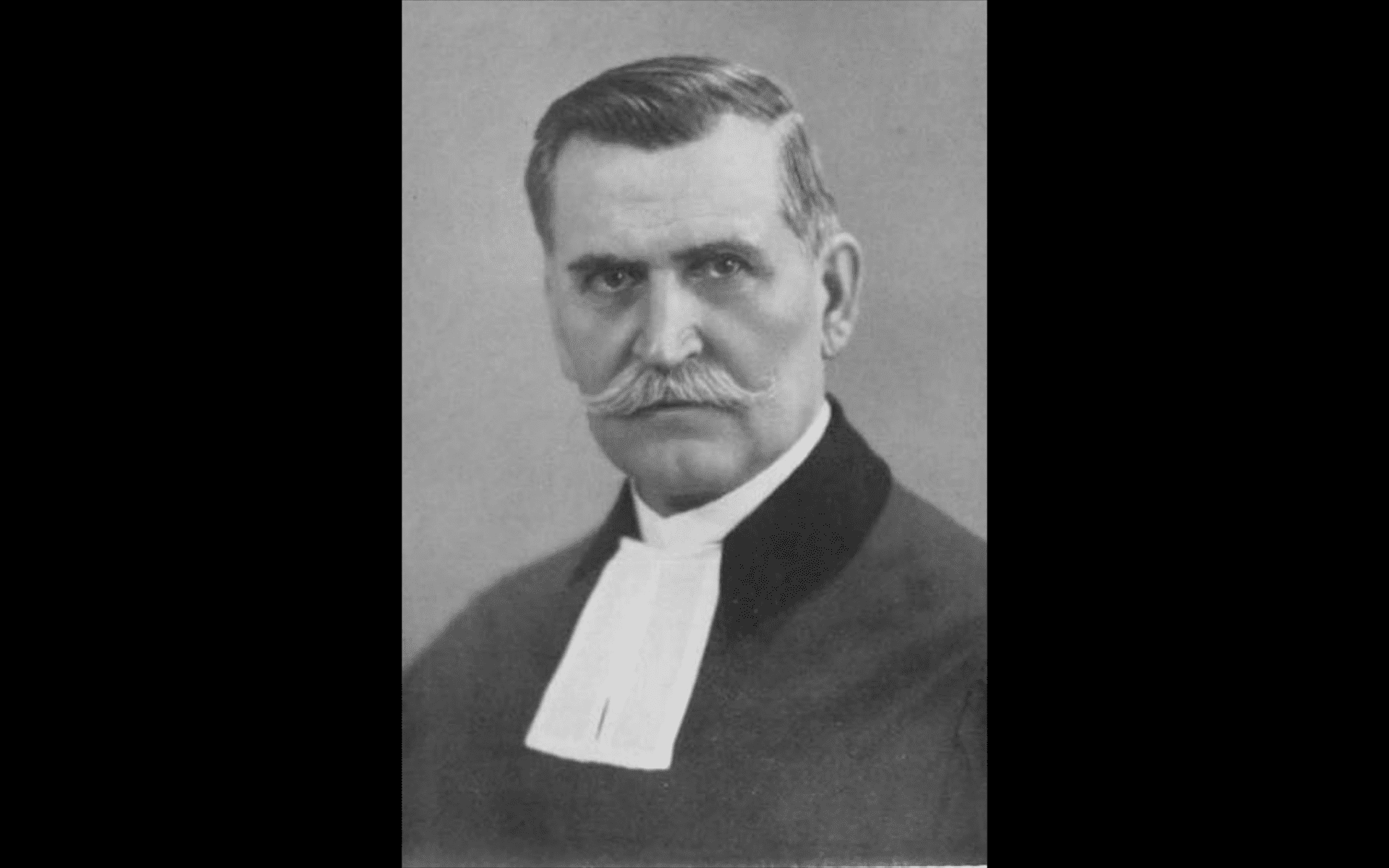

Sándor Raffay, Lutheran bishop and theological academic, member of the upper house and writer, was born on 12 June 1866 in Cegléd. His parents, János Raffay and Judit Szokol, came from an industrial family. He was always proud of his ancestors, and in his autobiography, which remains in manuscript and can be read in the Lutheran Archives, he noted: ‘Forty years ago, I myself read the note in the Turán (Túróc country) village minutes: June 20, 1606, János Raffay, a free man, bought land. I’m sorry that I didn’t make an authentic copy of this then, because this page has been torn out since. My grandfather was born in Turan.’[i] (A play on words: Turán was both the name of the village and the mythical ancient homeland of the Hungarians – the Ed.).

In terms of his upbringing, he studied at the civil school in Cegléd and Szarvas, then studied law at the University of Budapest. He began his theological studies in Pozsony (today: Bratislava in Slovakia) in the fall of 1887, and studied abroad between 1890 and 1892 in Jena, Leipzig and Basel. As he wrote, during his upbringing he experienced the value of the Monarchy’s liberal, colourful society. ‘Due to the friendliness of religious relations, we never experienced religious tension. The Jews also all adapted to us, and many Christian children were admitted to the denominational Jewish school, because they had good teachers. That is why I profess religious tolerance. Even later, I had friends whose religion I never knew. However, we have heard of cases where some of the mixed marriages were annulled, so it was often discussed in the family circle that mixed marriages should not be entered into. As far as I know, there has never been a mixed marriage in my family. Only my nephew Ferenc and my brother László married a Catholic woman.’ He completed his studies in Germany with great enthusiasm: ‘I longed for Germany like I longed for Paradise.’ From 1906, he was a teacher of Lutheran theology in Bratislava, and from 1908, a pastor in Budapest.

In 1918, he was elected bishop of the Bánya Lutheran Church District. From 1937, he was also a member of the parliamentary upper house. His representative activities focused primarily on church politics and cultural topics. At the beginning of 1938, in a newspaper article, he condemned extreme right-wing and left-wing politics, the Arrow Cross people and the anti-clericalism of Nazi Germany: ‘I myself believe that extreme politics, whether right-wing or left-wing, is equally half-hearted, harmful and dangerous. […] The extremists may have arrows or no arrows, stars or crosses, may call themselves Hungarians or Marxists, the sane Hungarian public and the historic Christian churches that maintain the nation must protest against all kinds of extremism in the interests of national existence and the tranquillity national life. […] The behaviour of the right-wing extremism against the historical churches and the holy religion inherited from our fathers […] is well-shown by Germany.’

The scholar Randolph L. Braham elaborated on his activities on one of the inevitable topics of the era, the so-called ‘Jewish question’, mentioning that Raffay supported the first and second anti-Jewish laws, but objected to the racial provisions of the second Jewish law. His position reflected the general opinion of the church leaders of the time. In his memoirs, he elaborated on his stance on the subject: ‘I have never approved of one-sided anti-Semitism. For this reason, during the flowering of the Christian system, I had many arguments with the politician Károly Wolff. ( Former prime minister of Hungary: Gyula Gömbös) Gömbös also made anti-Semitism the axis of his racial protection. I agreed with them that the backward, oppressed and neglected ethnic Hungarians should be embraced and strengthened in every way, but this nation-building work does not necessitate the persecution of ethnic groups of other races. Caring for, helping, and prioritizing our own blood necessarily entails pushing aside those of foreign blood in some way, but this can also happen in a humane way, there is no need to go astray on the path of breaking the law and inhumanity.’ Because of his contemporary expressions, he was repeatedly attacked by Egyenlőség (Equality), the Jewish political weekly associated with neology. In his 1925 interview, Raffay spoke about the fact that he was never anti-Semitic and that the racist press often misquotes his words.

During the Holocaust, according to some, Raffay came into possession of the so-called ‘Auschwitz protocols’ at the beginning of May 1944, and in September of the same year he intervened in the case of converted Jews with Governor Miklós Horthy. According to him, the Christian churches were ‘bankrupt’ when persons of Jewish origin belonging to the Christian churches were not sufficiently protected. His proposal for cooperation was rejected by Catholic Cardinal Justinián Serédi. In May 1944, Raffay appointed Gábor Sztehlo as the pastor responsible for the children of Jewish labour servicemen and converted Jews. He reflected on the German occupation in particular detail in his diary, and was one of the few memoirists who wrote extensively about the role of the Hungarian public administration, especially after the Arrow Cross coup. ‘It is completely incomprehensible how quickly the entire public administration, the army and the entire public opinion switched to the camp of the Arrow Cross party. In this way, anyone could have made a political turn in this country! And Horthy was immediately abandoned. His ministers partly captured and partly fled, Szálasi became the master of the moment without opposition. The reason why Horthy fell like this from one hour to the next is not only in himself, but also in his environment. He himself was indecisive, easily influenced, a toy of family and clique rule. He never had an independent view on public affairs. He never had an independent position on anything.’ Here Raffay blamed Horthy with clichés that have since then been refuted by historians: it is not true that Horthy was a mere puppet. Yet, Raffay took a more apologetic stance regarding the deportations, first mentioning the names of collaborationist secretaries of state László Endre and László Baky, and then adding that the deportations ‘were not carried out by them, but by the Germans, who laid on us in a disgraceful manner’ – this, again, was not entirely true, as the deportations were mostly the crime of the collaborationist Hungarian bureaucrats.

During the “liberation” – that is, the Soviet occupation that replaced one totalitarian system with another – the old bishop hid in Deák Square, suffered personal atrocities and deprivation. In his memoirs he stated: ‘So now the siege of Budapest is over. Three hells descended on us. The first was the Germans. They looted us thoroughly, but they did not touch our women. The system was tolerable. Then came the Arrow Cross hell. This was not just looting, but outright robbery, murder, trampling on everything that is law and order and decency. Weapons were put in the hands of children and they wielded them without restraint or discernment. People were persecuted and killed, not only Jews, but also Christians. Their rampage were disgusting. More inhumane, more selfish, and viler than later Russians.’ He also wrote about the Soviet terror later, stating that ‘what the German propaganda said about the rampages of the Russians is a mild children’s tale compared to the harsh reality. There is no limit to the lack of control of the Russian soldier’. In his memoirs, he also revised his feelings about Judaism, albeit in a negative way. ‘Jews are now showing their true nature. Abominable, ungrateful, insolent people. I have never been anti-Semitic, but now I have become one and I am beginning to regret everything that I did in previous governments to ease their persecution. They didn’t deserve it. When one looks at the communist movement and the speeches given there, it is obvious to everyone that the Jews are trying to rule the country. And as stupid as the citizenry and the intelligentsia are, they will achieve this aspiration soon and without hindrance.’ Of course, all of this does not change the fact that he spoke out for the converts during the Holocaust period, and his activities for rescue are not erased by his later, private comments – as regrettable as they were.

Sándor Raffay – after twenty-seven years – resigned from his position as Lutheran bishop in June 1945 and was succeeded by Lajos Ordass. The old man, living in complete seclusion, fell seriously ill and died in Budapest on 4 November 1947. His grave is located in the cemetery on Kerepesi road. His biography and writings reveal a complicated man, who nevertheless could stand up for some of the persecuted people during the past century, even if his personal feelings urged him not to.

[i] For this and all subsequent quotes see the personal papers of Sándor Raffay in the Evangélikus Országos Levéltár (Hungarian Lutheran Archives). The papers have no special reference or code number.