Background

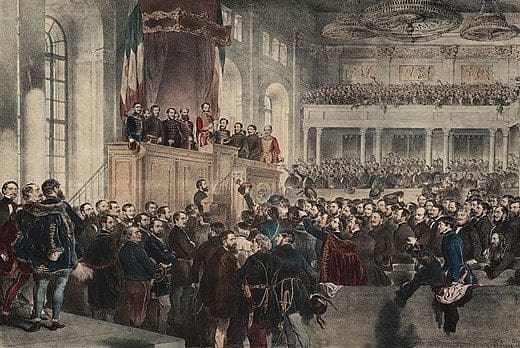

In Hungary, at the “Diet” (Parliament) of 1825–1827, the Viennese court renounced the imperial system of government and restored the dualism of the Estates. At that time, the Diet was still dominated by grievance politics, and the restoration of the dualism of Estates opened up the debate on national politics again.

Later, in the 1930s, a liberal opposition to reform emerged alongside the traditional opposition to grievance.[1] By the end of the decade, the neo-conservative movement, led by Aurél Dessewffy (1808–1842), emerged, with the aim of aligning modernisation with the interests of the empire and royal power.[2] Out of these two reformist tendencies grew the liberal-conservative opposition, which revolved around the essence of the reforms.[3] During this period, the court was on the defensive, supporting the conservatives and trying to block reforms that threatened the balance of power, but it did not pursue an independent modernisation programme.[4] This political constellation continued, with minor changes, until 1848, when the liberals took advantage of a favourable foreign policy turn (Paris Revolution) to implement their own modernisation programme. (April Laws.) The so-called constitutional revolution was legitimate in vain, as it was unacceptable to the Habsburg elite and was legitimised only in a tight situation. The struggle for freedom that followed the revolution, or as a bishop’s note to the monarch called it, the ‘internal war[5]‘, also involved serious internal political struggles on the Austrian side.

Already during the suppression of the Hungarian War of Independence, the centralist modernist forces in Austria had overcome the conservatives, and using their military victory as an opportunity, they began to implement their ‘New Austria’ programme, while at the same time the Hungarian conservative forces were defeated, since they too had emerged as the opponents of the Schwarzenberg-Bach unitary state. Because of the defeat of the counter-revolutionary forces, we cannot speak of a “counter-revolutionary Austria”, in practice the counter-revolution as defined by Joseph de Maistre as the restoration of order or at least the restoration of the previous state of affairs failed to materialise, there was retaliation, but the new system was neither a restoration nor a renovation of the pre-revolutionary system. The Olomouc Constitution of 4 March 1849 was nothing more than the beginning of the instauration of the empire.

The Way of the Federal Empire, and the Conservatives

For nearly 10 years, the conservatives were in the systemic opposition, during which time they carried out more than one protest action or attempted to influence Austrian decision-makers

For nearly 10 years, the conservatives were in the systemic opposition, during which time they carried out more than one protest action or attempted to influence Austrian decision-makers. Their efforts have not gone unanswered by the government. In 1850, for example, they addressed a public memorial to the Emperor calling for the restoration of the rule of law, László Szőgyény-Marich (1806–1893) notes in his memoirs that ‘…the ministry has unquestioningly flared up a rage against us – conservatives.’[6] No open action was taken, as they had nothing to show against the conservatives, but they tried to squeeze them out of economic and political life.

Nine years later, on 24 June 1859, the Austrian troops were defeated at Solferino, and four days later, the foreign minister, Count Johann Bernhard von Rechberg-Rothenlöwen (1806-1899), was forced to grope for a solution to the ‘Hungarian cause’ with the conservative Baron Jósika Samuel (1805–1860). Jósika sent the minister to Emil Dessewffy (1814–1866), one of the leaders of the conservatives, and Dessewffy received the news of the peace of Villafranche on 14 July 1859. He then drew up a plan on 15 and 16 July, detailing the need for the reconstruction of the monarchy, the principles to be followed and the way in which it was to be carried out. On 15 August Dessewffy presented his plan to the Foreign Minister.

Tervezete egy hadjáratnak Ausztria belsejében, hogy az 1859. évi szerencsétlen háború következéseinek eleje vétessék és tartós erőhöz lehessen jutni.[7] The title of his paper is divided into 8 parts. In his work he analysed the state of the empire, the failure of the reforms to date and the reasons for this, and presented a draft federal constitution.

Dessewffy would have restored the Hungarian, Croatian and Transylvanian constitutions in such a way that three aspects would have been fulfilled: 1. abolition of the noble tax exemption, 2. abolition of the gentry tax, 3. extension of the military service. Restoration of the monarchy’s constitutional order in the parts of the Monarchy outside Hungary, with the addition of peasant and civil representation.

At the same time, he proposed a radical administrative reform in which some of the existing provinces would have been merged into several groups, such as Moravia and Silesia, with Upper and Lower Austria, and Salzburg, Styria, Carinthia and Carinthia, The remainder of Bohemia would have formed a separate unit, while Galicia and Bukovina were also to be unified, as were also Illyria and the coast, and the Venetian provinces were to form a separate unit and the unified Tyrol and Voralberg a separate province.

The existing Imperial Council was to be transformed into the Emperor’s Constitutional, Ordinary, Legislative and Financial Council, which was to be competent, according to his conception, in matters affecting the monarchy as a whole. The Imperial Council could be convened by the Emperor in December each year for a maximum of three months. It would then discuss tax laws, as well as those relating to customs, money and banking, and recruitment. A law could be initiated by both the council and the government, the former subject to restrictions. The government could not borrow money or levy new taxes, nor could it raise them, without the approval of the Imperial Council. And the budget always had to be submitted to the government for discussion a year in advance.

In March 1860, the Emperor created a strengthened Imperial Council, composed of delegates from the countries and life peers, but until the electoral system was worked out, the Emperor appointed 38 members. Its responsibilities included setting the state budget, examining the state accounts and debating bills and proposals from national deputies. The council did not, however, have the power to initiate legislation. Through persistent work, Antal Szécsen succeeded in gaining enough supporters in the council to successfully propose a motion to start the process of resolving the Hungarian question. As a result, Emil Dessewffy developed a new, detailed concept of his earlier draft, adapted to the circumstances.

In this “second campaign” in nuce Dessewffy would abolish the ministries of religion, justice and police, their functions to be taken over by newly created imperial commissions and directorates.[8] He wanted to restore the Hungarian Court Chancellery and abolish the Ministry of the Interior, whose functions would be taken over by the restored unified Court Chancellery, which he divided into further vice-chancellorates.[9] Thus, from a jurisdictional point of view, the draft constitution separated the administration of the Kingdom of Hungary from that of the rest of the Empire. It restored the Seven-Personed Table and the Royal Table, as well as the counties, by making the abolition of noble privileges (monopoly of office) and serfdom a fundamental principle. He renamed the former governorates as governorates, which would have been based in Galicia, Venice, Vienna (for Lower Austria, Moravia, Silesia and Salzburg), Graz (for Styria, Carinthia and Carinthia), Prague (for Bohemia) and Cluj (for Transylvania).[10]

Dessewffy also drafted a diploma to be issued in the name of the Emperor. Caesareo-regium diploma consolidatorium et complementorium sanctionis pragmaticae, in his preamble he listed the necessary changes in five points:

1. It imagines a single monarchy in the future.

2. It renounces the right of the monarch to determine alone the increase of existing taxes or the imposition of new ones, and does the same for duties, taxes and other sources of revenue.

3. Subsequently, two subsections dealt with jurisdictional matters, all joint matters relating to the financing of state expenditure (taxes, duties, customs, etc.), the army and monetary policy (“legal tender”) were to be dealt with by the imperial parliament, while all other matters were to be dealt with by the national parliaments.[11]

4. The annual convocation of the national parliaments in December and the imperial parliament in April.

5. To introduce diplomas and translate them into the languages of the peoples of the empire.

Dessewffy imagined a fragmented empire divided into (member) states sharing sovereignty and thus creating a higher political integration

The draft itself contained radical elements, such as the reorganisation of the imperial administration, which would have torn apart the countries of Count St. Wenceslas’s crown and created countries that never existed. This is difficult to understand from a man who bases his policy on historical traditions and the specific characteristics of Hungary, because it is nothing other than ignoring historical characteristics. Even István Schlett, the most detailed descriptor of Hungarian political thought, could not name what could have motivated Dessewffy. He concludes, on the basis of Dessewffy’s letter to Jósika[12], that, unlike the imperial constitution of 1849, Dessewffy imagined a fragmented empire divided into (member) states sharing sovereignty and thus creating a higher political integration.[13] In my opinion, this idea is the key to this reform, which does not fit into the conservative concept. The Count’s aim was probably to create ‘viable’ countries with sufficient resources to defend their sovereignty in the event that central power moved back towards the concept of a unitary state. On the other hand, agreeing with Schlettel, it can be deduced that in Dessewffy’s concept all member states would be constitutional states, so that there would be a common ground against strong imperial power, as a result of which Hungary (and the Hungarian elite) would be able to line up allies against the centre.[14] In this concept, Hungary would have been in a strong position of power, and given its size and population, it would have been virtually the largest unit of the empire, which would have made the Hungarian Parliament inescapable in informal imperial politics, and in this it is not difficult to see the objective of Aurel Dessewffy, who died in 1842.[15] Dessewffy’s draft had a significant influence on the October Diploma of 20 October 1860, but the Diploma – despite its federalist character – also contained centralist elements, and its mixture of elements did not satisfy Hungarian conservatives, Hungarian public opinion or the supporters of centralisation in Vienna, but it was a step towards the reconciliation that was later concluded (with conservative help).

The main objective of the Hungarian conservatives was to create a political integration compatible with the national and cultural diversity of Central Europe. This is why the federal state structure was chosen, as conservative publicist Sándor Lipthay notes: ‘By their very essence, they likewise defend the national autonomy and nationality of the parts of the Union.’[16][17]At the same time, this imperial political integration would have protected the nations of Central Europe against threats from both the West and the East.

The era has two lessons for the people of our time. 1. The Central European states need some form of political integration to defend their sovereignty. (This is particularly relevant in the light of the situation in Ukraine.) 2. This integration not allowed – and could not, as the failed neo-absolutist experiment has shown – go beyond the federal level of integration, because of the cultural and ethnic diversity of the region.

[1] Tamás Dobszay, ‘A rendi országgyűlés utolsó évtizedei (1790-1848)‘, Budapest, Országház Könyvkiadó (2019), 415.

[2] Tamás Dobszay, ‘A rendi országgyűlés utolsó évtizedei (1790-1848)’, Budapest, Országház Könyvkiadó (2019), 432.

[3] István Schlett, ‘A politikai gondolkodástörténete Magyarországon’, vol. I., Budapest, Századvég (2018), 432p.

[4]Tamás Dobszay, ‘A rendi országgyűlés utolsó évtizedei (1790-1848)’, Budapest, Országház Könyvkiadó (2019), 438.

[5] Mihály Horváth, ‘Magyarország függetlenségi harczának története 1848 és 1849-ben’, vol. II. Pest, Ráth Mór (1872), 32-36.

[6] ‘Idősb Szőgyény-Marich László országbíró emlékiratai’, vol, II. Budapest, Hornyánszky Viktor cs. és kir. udvari könyvnyomdája (1917), 13.

[7] Manó Kónyi, ‘Deák Ferencz beszédei 1848-1861‘, (A plan for a campaign in the interior of Austria, in order to avert the consequences of the unfortunate war of 1859 and to gain a lasting force.), Budapest, Franklin-Társulat, (1903), 426-434.

[8] Manó Kónyi, ‘Deák Ferencz beszédei 1848-1861’, vol. II. Budapest, Franklin-Társulat (1903), 463.

[9] Galician and Italian.

[10] Manó Kónyi, ‘Deák Ferencz beszédei 1848-1861’, vol. II. Budapest, Franklin-Társulat (1903), 464.

[11] Manó Kónyi, ‘Deák Ferencz beszédei 1848-1861’, vol. II. Budapest, Franklin-Társulat (1903), 474-475.

[12] Manó Kónyi, ‘Deák Ferencz beszédei 1848-1861’, vol. II. Budapest, Franklin-Társulat (1903), 440-449.

[13] István Schlett, ‘A politikai gondolkodástörténete Magyarországon’, vol. II. Budapest, Századvég (2018), 120.

[14] István Schlett, ‘A politikai gondolkodástörténete Magyarországon’, vol. II., Budapest, Századvég (2018) 119.

[15] Read more about Aurél Dessewffy’s informal concept of power: Iván Zoltán Dénes, ‘Liberális kihívásra adott konzervatív válasz’. Budapest, Argumentum kiadó (2008), 49.

[16] By union Lipthay means federation, the term used in the period to describe this state structure. See United States of America.

[17] Sándor Lipthay, ‘Tanulmányok az általános és különösen magyar-osztrák egyesülési jog (uniojog) továbbá Magyarország közjogának alaptartalma és a Király alapjogai’, vol, II. Pest, Kertész József Gyorssajtónyomása (1864), 50.