The following is an adapted version of an article written by Emese Hulej, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

A great number of spy stories and best-selling adventure novels are linked to the name of András Berkesi. And besides, just for the record, brutal interrogations, torture, and the suffering of innocent people in the gulag as well. The story of a life of lies below, in the presentation of Magyar Krónika.

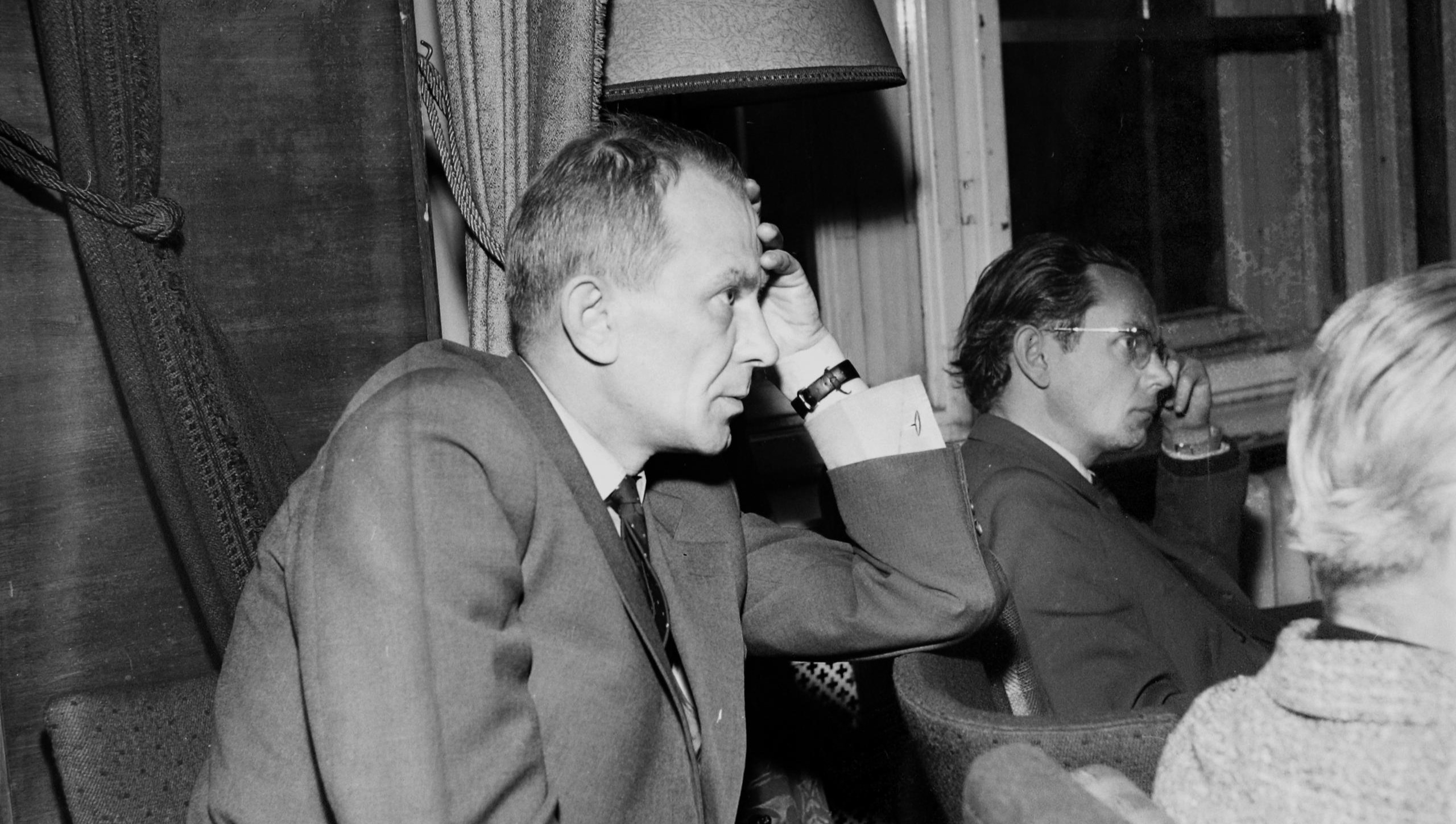

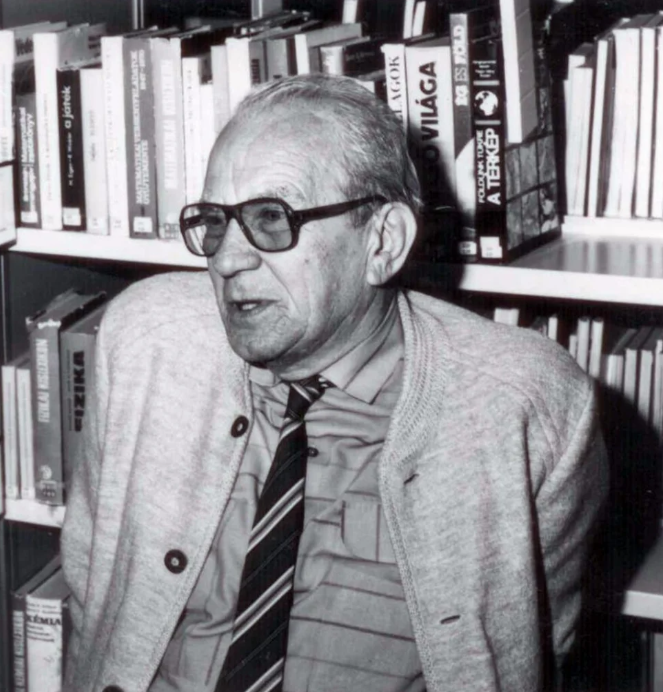

Writer–reader meeting in Körmend, 30 October 1989. Many people came to the town library, as the books of the author, almost 70 years old, could be found on the bookshelves of most families back in the day. András Berkesi was, along with Mór Jókai and Magda Szabó, one of the best-selling authors of the time.

Then something happened. A young man indicated that he had a question. However, he did not ask the author about his creative process, but why he had not dealt with his past—with the fact that as one of the most brutal interrogators of the State Protection Authority (Hungarian: Államvédelmi Hatóság, ÁVH) in the 1950s, he had got many people into the hands of the Russians, people who then spent several years in the gulag.

The air froze—people were not very happy about the unexpected turn of events. ‘What does he want? This is not why we came here,’ people murmured. At first, Berkesi was still somewhat confident, firmly denying the accusations, saying that he was a working-class writer, had never been a member of the ÁVH, and, besides, whoever accused him should provide some kind of proof.

At this point, an elderly man, Sándor Nagy, who had spent years in the gulag and was a well-known and respected resident of the town, rose from one of the back rows, saying:

‘Here I am, Sándor Nagy. A living witness. It was you who took me away from here in August 1948 and told me that I would never see the day of God again and that even my bones will never be accounted for.’

The atmosphere changed at once. The writer was practically forced to flee, but the fact that he was able to live his life without any accountability until his death after the regime change is deplorable. A month later, Hungarian Television also broadcast a portrait of Berkesi, who was celebrating his 70th birthday, after which it received indignant letters from viewers who had not met the writer during a friendly chat but while he was torturing them in beastly ways.

‘The fact that he was able to live his life without any accountability until his death after the regime change is deplorable’

Berkesi was a textile factory worker as a young man and committed himself to the communists in 1945. He became a military intelligence officer and, after its formation, served in the ÁVH. First in Szombathely, then in Szeged, he directed the work of the counterintelligence and conducted interrogations.

It was in Szombathely that Sándor Böröcz, a Lutheran pastor, was dragged away from his newborn daughter and forced to ‘confess’ by his post-natal wife being defiled. The young priest was, of course, guiltless, not a spy, just a preacher and demander of Jesus’ principles. Böröcz, who was later also imprisoned in the gulag, gave a detailed account of Berkesi’s brutal methods as well: kicking, slapping, tamping out cigarette butts on the body, hitting the base of the ear hard, forcing the victim to stand against the wall for days, beating the feet, and mental torture.

Berkesi once told a prisoner that he also drew ideas from Chinese books to loosen prisoners’ tongues, and in one of them, he read that prisoners’ legs could be locked in a box full of hungry rats.

By the way, the author was himself the victim of a show trial in 1950, serving four years in prison. After his release, he worked in a factory in Kőbánya, but interestingly enough, during the 1956 Revolution, he was already among the guards defending the József Attila Street wing of the Ministry of the Interior. As a loyal party soldier, he fought with arms alongside his former fellow prisoner and later colleague, György Kardos, who ran the Magvető Publishing House for many years.

In the 60s and 70s Berkesi said several times that he became a writer in prison, where he kept polishing his stories in his head. Yet his first book is about the ‘counter-revolution’, where his protagonists Erzsi and Laci quickly realize where they belong and where the truth lies… It was this novel, the October Storm (Októberi vihar), that launched his career.

He later wrote a multitude of spy stories and adventure novels, becoming one of the star authors of the era. Several of his novels were made into films and were broadcast on television as well, including the series Thresholds (Küszöbök). The Mermaid on the Signet Ring (Sellő a pecsétgyűrűn) is still available on the Internet, starring such famous Hungarian actors as Zoltán Latinovits, Hilda Gobbi, László Mensáros, György Kálmán, Sándor Pécsi, and Judit Halász.

The popular author was also awarded the Attila József Prize while he has enjoyed the trust and support of György Aczél.

Officially, no one has ever held him accountable for torturing, humiliating, and handing over people to the Russians to be taken to the gulag. András Berkesi died unharmed in September 1997.

This article is based on research by András Murai, Brigitta Németh, and Katalin Mirák.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.