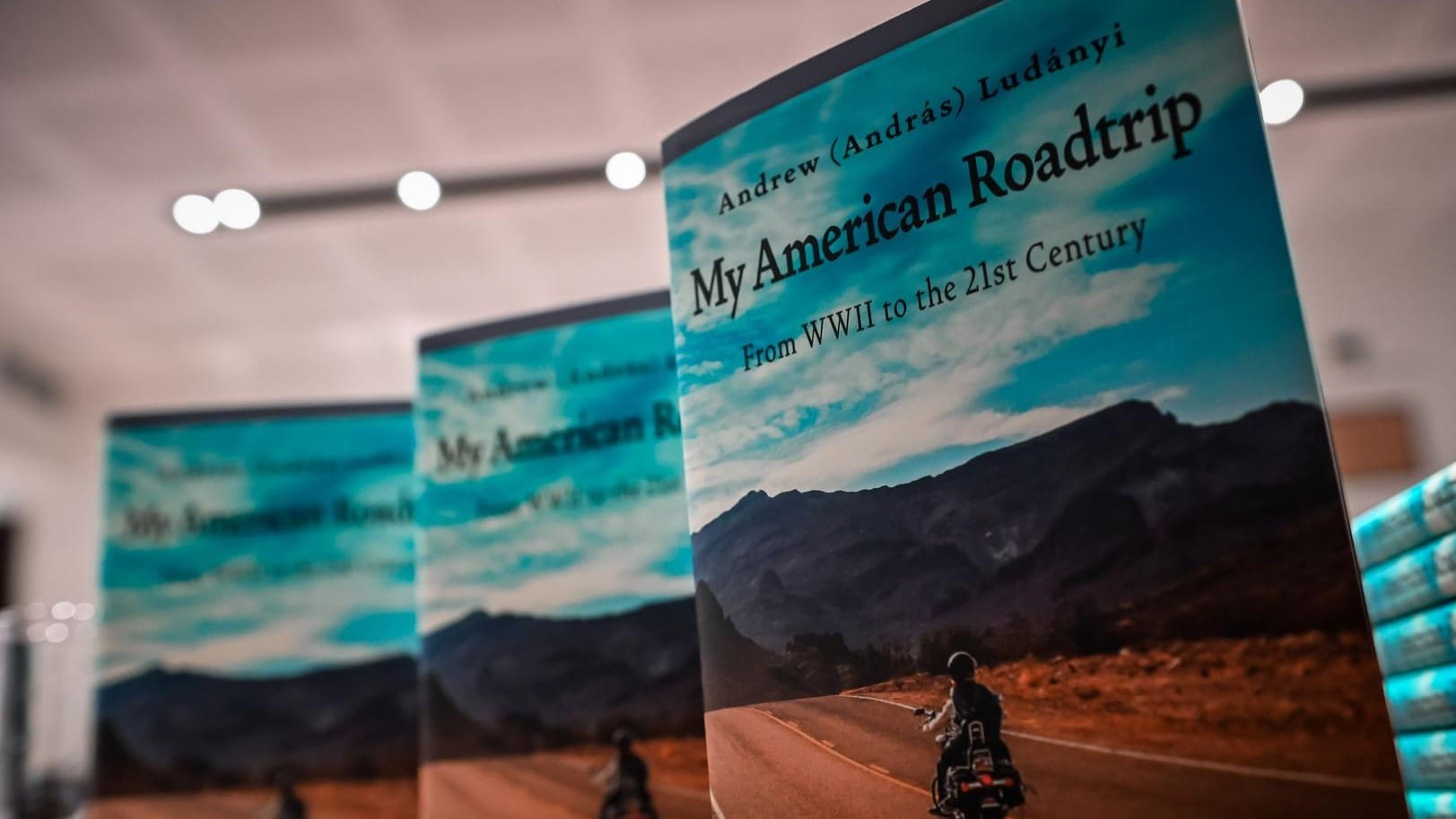

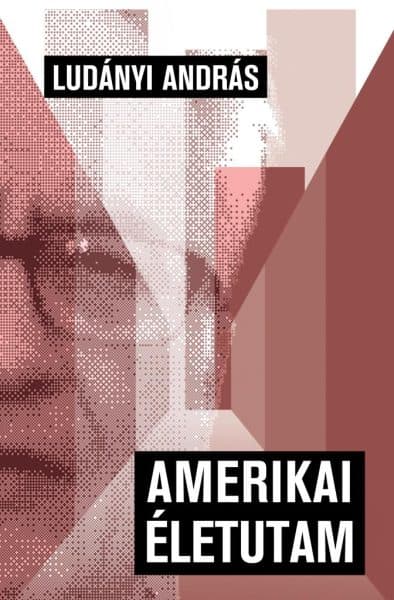

‘András Ludányi’s memoir provides a unique and comprehensive overview of the life of Hungarian American emigration from World War II to the present day…through his personal reflections, he makes a rare and valuable contribution to the understanding of American domestic and foreign policy and Hungarian–American relations…It is difficult to decide whether it will be of more interest to the American, the Hungarian or the Hungarian American audience…But I am certain that it will serve well the cause of understanding and deepening Hungarian–American relations,’ Zsolt Németh, Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Hungarian parliament and head of the Hungarian Delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly to the Council of Europe wrote in his recommendation of the book published by Méry Ratio with the support of the Pro Minoritate Foundation for Minorities in 2020.

I love reading biographies. However, despite growing up in Transylvania and living decades in Hungary, I may not have read this book at all or would have been as engaged with it as I am now were I not living in the United States now and getting acquainted first-hand, through my family and work, with countless well-known and less known personalities of the Hungarian American diaspora, its past challenges and joys, its present ups and downs, and its future opportunities. The book written in Hungarian, with an English version published in 2023, is a mixture of various genres ranging from autobiography, written oral history, documentary, political history, family history, academic material, and entertaining writing. It follows four parallel tracks: the author’s personal and family life, Hungarian community life, his professional career, American public life and American foreign policy.

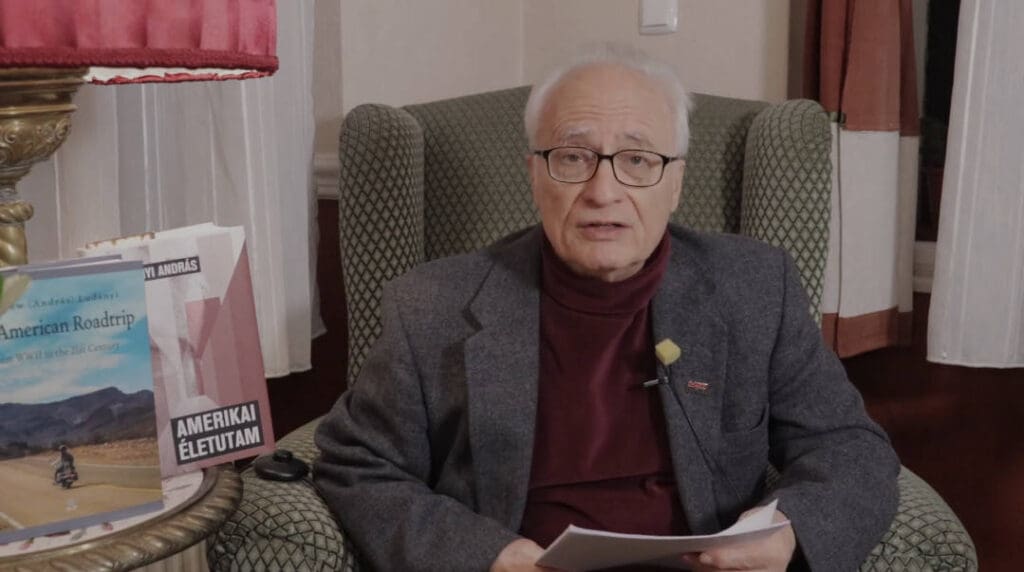

Political scientist, sociologist and historian András Ludányi (Andrew Ludanyi) was born in 1940 in Szikszó, Hungary as the third child of Colonel Antal Ludányi and Erzsébet Ludányi Prileszky. The family emigrated when he was a child and he grew up in the US, after experiencing the hardships of the post-war flight, the atmosphere of the refugee camps in Austria, and

the difficulties of arriving and settling in the New World as a displaced person.

He experienced and dealt with segregation or the bullying by classmates who ridiculed him for wearing shorts, which he describes humorously in his book. Ludányi puts these stories in the context of world history, in order to make the reader better understand certain aspects of his family’s fate, such as the sudden and drastic drop in his parents’ social and financial status, or the strongly assimilationist immigration policies in the US of that time.

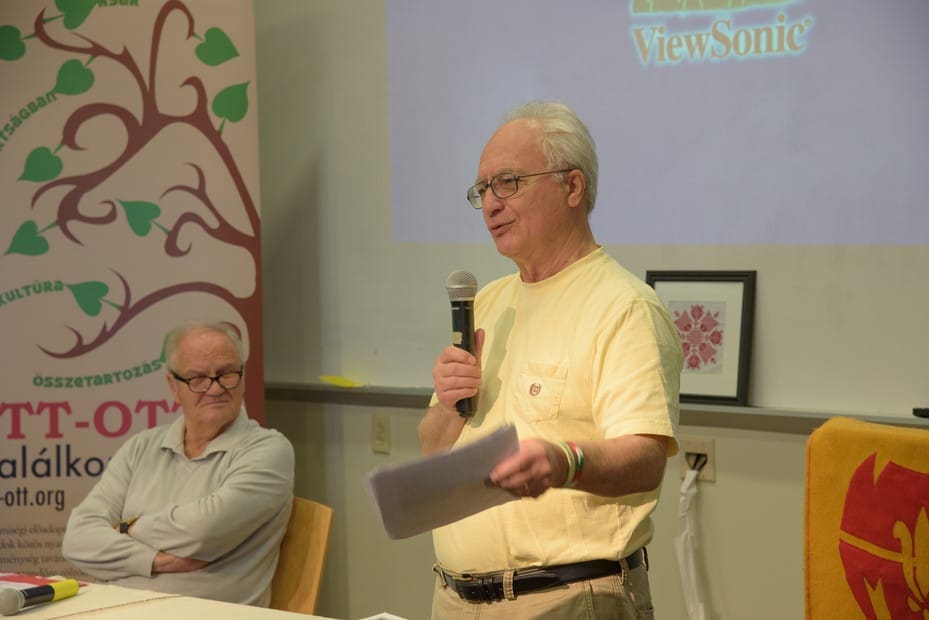

The period of his youth, with its frequent moves, gave him the opportunity to experience both rural and metropolitan America. Leaving the farm in Virginia, he became a student and a scout (shooter) in New York, then a history graduate with honors at Elmhurst College in Illinois, supporting himself by working as a cleaner. He then obtained his post-graduate degree in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and finally got a job as a teacher and researcher at the University of Ohio in Ada. In the meantime, he was an enthusiastic organizer of the HCF and the ITT-OTT conferences, as well as an active member of other Hungarian American organizations that were often at odds with each other. He also explored Vojvodina, Serbia as a student, and later travelled to Transylvania, Romania relatively often.

During his outstanding, yet in many ways typical Hungarian American life, Ludányi experienced the vulnerability of American farmers, the life of the post-WWII refugees and Hungarians living beyond the borders of Hungary, appreciated both manual and intellectual labor, experienced the difficulties of making ends meets as well as relative financial stability, learned to trust the strength of family ties and also that of the communities, and tried to find his way in the academic world as well as in Hungarian American public life. In the meantime, he was first an advocate of the cause, and then an active shaper of the fate of Hungarians locked behind the Iron Curtain, not only in Hungary but also beyond the Trianon borders, such as Hungarian communities in Vojvodina and Transylvania, while his parents, and later himself, struggled to survive and move forward in the new world.

The roots of his commitment and perseverance can be found in the conservative values of his family and of the Hungarian scouting movement in exteris: he was raised in Hungarian national pride with the conscious preservation of the Hungarian language and history and

these factors contributed to his having a Hungarian heart, mind and language.

The author’s family background and his own family life (as well as the lives of many other Hungarian Americans committed to preserving and transmitting Hungarian language and culture) refute some misconceptions of the 20th century. These popular belief held that children born and/or raised abroad (in this case in the US) do not (and should not) speak their mother tongue (even with two Hungarian parents), that first-generation American citizens can only assimilate, i.e. study, work and speak the language of the host country at home; and, moreover, earning a living in the US does not give enough time and opportunity to develop and preserve the Hungarian identity of the next generation, i.e. to actively participate in the lives of Hungarian communities of this diaspora.

These typically weekend-focused activities as well as the personal and family ties to Hungary (and, more broadly, to the Hungarian community in the Carpathian Basin) are effective and probably the only means of preserving the Hungarian identity, and involve considerable sacrifice and renunciation on the part of all family members. Like many other Hungarian American couples, Ludányi and his first wife, Julianna Rózsa (Panni) Nádas managed to raise their American-born daughters, Anna Csilla and Ilona Anikó, to speak Hungarian at a native level and to bond with Hungary.

His extraordinary public engagement is a proof that the Hungarian diaspora in the US can still have a raison d’être in the radically changed situation after the fall of communism, and a new common goal that transcends left-right divides and the Democratic–Republican opposition: the survival of the Hungarian diaspora.

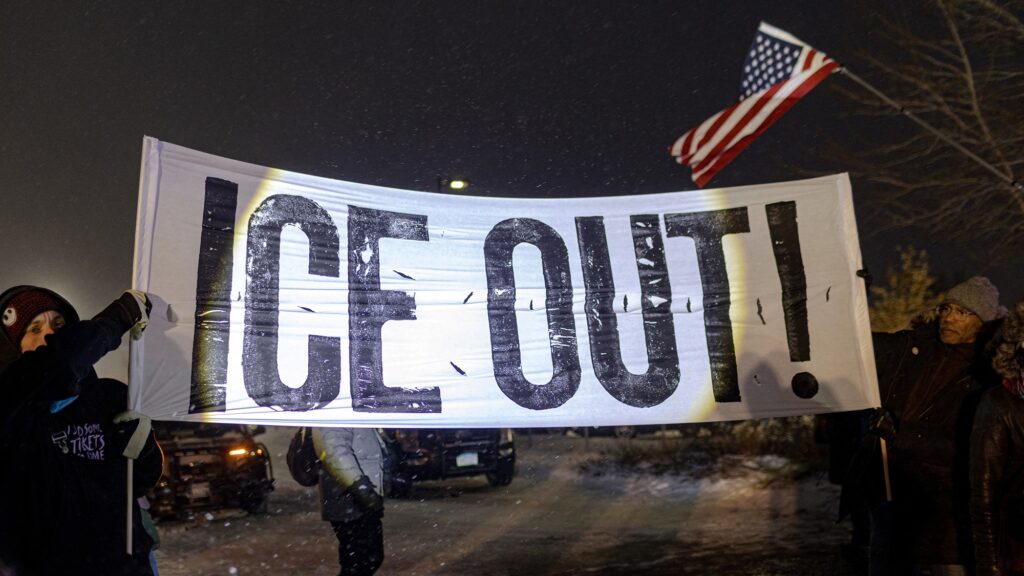

This book is also extremely valuable in several other aspects, for instance it sheds light on the complex structure of the Hungarian immigrant society as well as those of the Hungarian minorities in Transylvania and Vojvodina, and on its episodes less known to readers in the Hungarian homeland, thus providing valuable insights for those involved in diaspora studies, not only for interested non-professional readers. Ludányi’s critiques of the fragmented nature of the Hungarian immigrant society in North America also fit well into his brief analyzes of the history of the development of American society. He also provides, in relation to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, a detailed analysis of the negative effects and consequences of US colonial foreign policy, including the disintegration of the American Dream. The description of Hungarian American human rights lobbying efforts and the struggles of Hungarians living across the current borders of Hungary asserting their minority rights is also a very valuable and useful part of the book, as is the work of the political scientist who, living in Hungary also analyzes in detail—including some constructive criticism—the Hungarian government’s national policy, acknowledging and supporting its efforts on behalf of the diaspora and all Hungarians living in the Carpathian Basin.

Beyond all these aspects, I found that the greatest strength of the book is the author’s reflective, self-critical approach, from the refugee camps in Austria through the events of 23 October 1956 and 11 September 2001 to the state of affairs of today’s Hungary (up until 2020 when the Hungarian manuscript was closed). He critically assesses the statements of several refugees and immigrants, the colonial foreign policies of the US, the cultural oppression of Hungarian minorities in Serbia and Romania, the Hungarian government’s national policy and its minor shortfalls, and the fallacies of the present opposition in Hungary—through the his own professional experience and his impressions of the American foreign policy.

In this respect, I found one single shortcoming—which, fortunately, does not detract from the value of the book. Notably, while the author, a self-confessed Democrat supporter, is able to think and write objectively about the activities of the current right-wing government in Hungary and its prime minister as well as the turbulent state of US–Hungarian relations, he is simply unable to take an objective view of the American political arena: he has perhaps not a single positive comment to make about the Republicans. Furthermore, despite being raised in a family sharing conservative values, he mentions absolutely nothing about his religion or faith, which also was and could still be a main source of cohesion for the Hungarian communities, both in the diaspora and in the Carpathian Basin.

His largely successful objectivity most probably also stems from scouting, which, according to the author, was

the only ‘unifying force above all else’ in the fragmented Hungarian immigrant society.

Those readers who have never been part of the movement can perhaps best understand this by the campfire metaphor, because the ‘embers and warmth of the campfires have stayed with us for better or worse’. This fate-shaping power is truly understood in a scene of the book in which a disappointment in a Hungarian youth camp in Vojvodina leads him to the conclusion: ‘you must have such a fire in your memories, in your soul, to survive as a nation’.

Having read the book and having known the Hungarian scout movement personally and through my work, I do not think it is an exaggeration to note that the embers of these campfires kept the community-building and organizing stamina of the Hungarian American diaspora alive, not only after the world wars, but also after ‘56 and later. And hopefully it will keep it glowing in the future, despite the author’s ‘restless anxiety as a first-generation American, who sees dark clouds gathering on the skies of the not-too-distant future’, which in his view are nowadays embodied primarily in self-destructive lifestyles, i.e. consumerism-driven globalization in the US, and the absence of strong civic self-organization in Hungary.