Budapest’s iconic Andrássy Avenue (Andrássy út), lined with palaces, villas and splendid apartment buildings, has become an uncontested symbol of the capital over time, and since 2002 it has also been a World Heritage Site—which is exactly what its creator would have wanted. Count Gyula Andrássy, prime minister of Hungary and subsequently foreign minister of Austro-Hungary, was determined to shape Budapest into a big city of European standards, one of the first steps of which was the construction of Andrássy Avenue itself.

In the 19th century, Chain Bridge was the first permanent bridge connecting Pest and Buda, the two sides of the city flanking the Danube. At the time, the two parts were not yet legally united, thus they were treated separately in most decisions. The Pest side was developing more dynamically, so former Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy decided to start urban management primarily there. Among other priorities, he considered it important to connect today’s city centre with City Park, the favourite park of the capital’s residents, as the only route leading to it was Király Street, which at the time was on the outskirts of Pest. Those who wanted to get away from the dullness of the city centre chose City Park as a place of relaxation and hiking, but the route they had to take led through narrow, dusty streets, past factories, vineyards and potato fields.

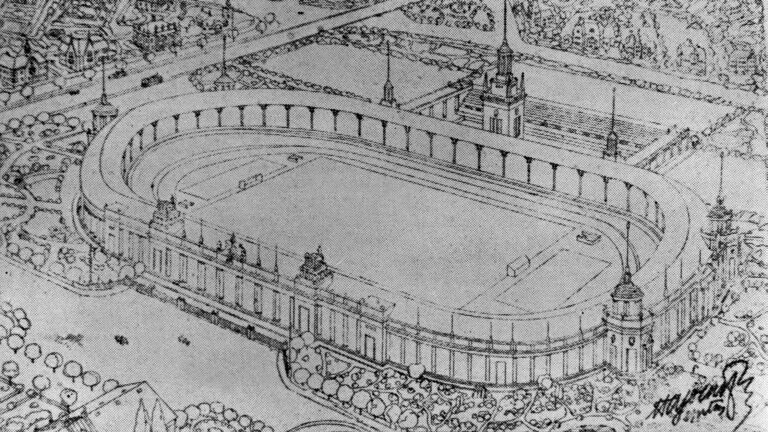

Andrássy presented his ideas about the new boulevard at a conference in 1868. The plan was not only to create a classy pedestrian avenue: it was intended to serve as a model for the gradual development of the areas around it. The project therefore included the extension of the avenue as well, with the interposition of two squares—Kodály körönd and Oktogon—and the construction of two-, three- and four-story palaces along the road, lined by plane trees typical of pedestrian roads.

The basic idea, as well as the functional design and the overall appearance were inspired by the Vienna Ring Road (Ringstrasse) and the Avenue des Champs Élysées in Paris.

However, contrary to the Viennese model, the initial plans did not include the centralization of public buildings along Andrássy Avenue, which continued to be built mostly in the centre of Pest and in Buda.

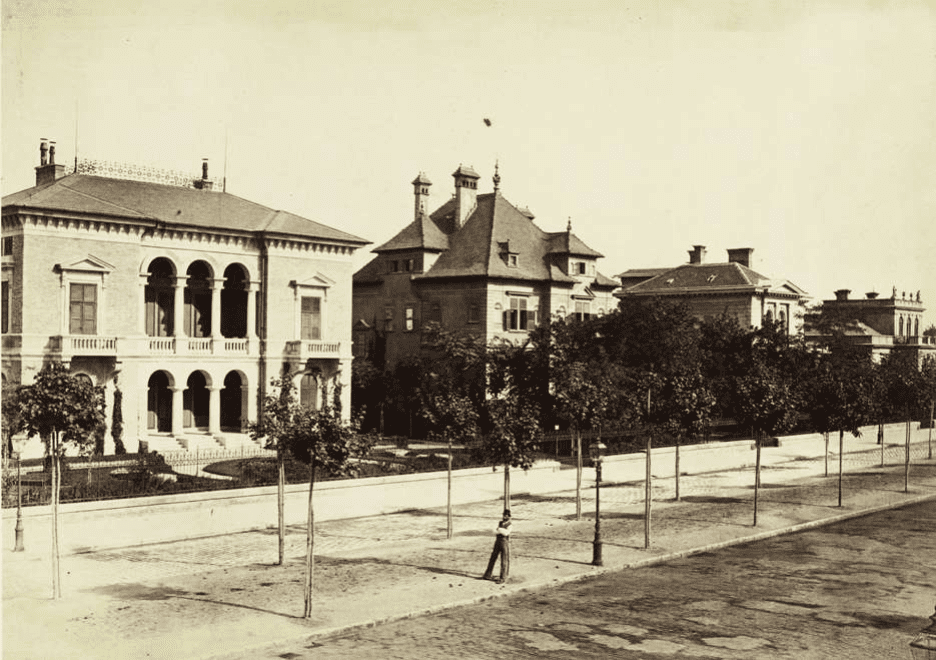

Nevertheless, buildings such as the Hungarian State Opera House and the Hungarian Railways (MÁV) apartment building (later the State Ballet Institute), the former Terézváros Casino, the Paris Department Store, the Old Art Gallery, the Academy of Music, and the University of Fine Arts were, and still are, located on the avenue, roughly up to Kodály körönd. From there, all the way to City Park, there is a row of villas, with mostly lower buildings and luxury apartment houses.

By 1885, when the avenue was inaugurated, elegant buildings had been erected on most of the plots, lined with plane trees. However, this state of tranquillity did not last long, as before the turn of the century the construction of an underground tram route, unique on the continent, began, with roadworks commencing. The reason for the creation of an underground railway was simple: the Budapest Public Works Council, which was partially responsible for the construction of the avenue, did not allow laying tram tracks on the surface, as they would have ‘spoiled’ the avenue’s elegance.

Click here to read the original article