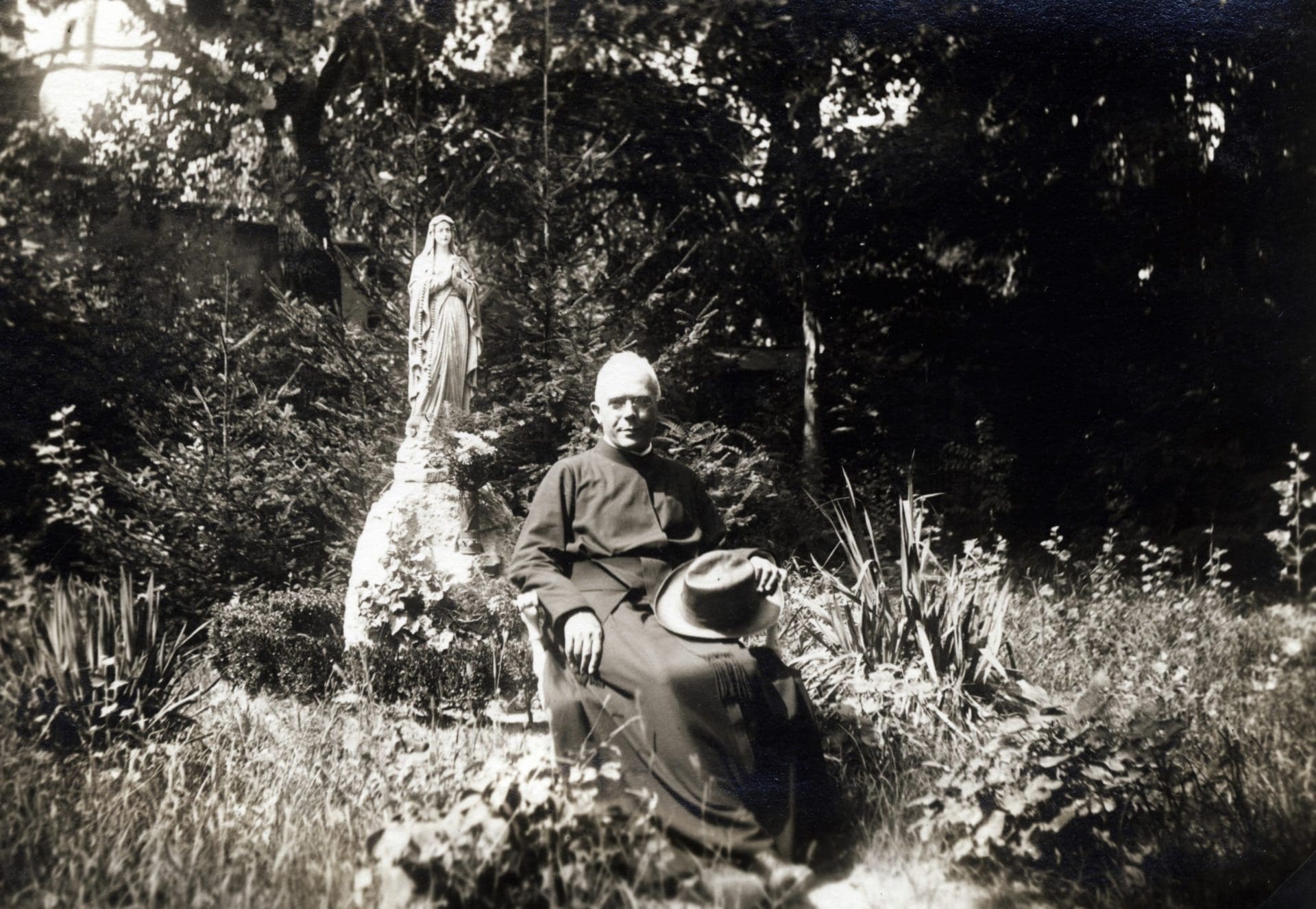

The Jesuit priest and newspaper editor Béla Bangha did a great deal to spread the Christian self-definition, which largely determined the public discourse of Hungary in the early twenties. As he recalled from 1927, ‘At that time we were giants, rulers and princes of public life.’[1] Bangha was born in 1880 in Nyitra (today in Slovakia). He was a Jesuit priest with great diligence and a great deal of organising skills, but his writings lacked the scholarship, prose or depth of Ottokár Prohászka’s texts. Today Bangha is seen as the chief representative of the ecclesia militans, the fighting church, although he had another side: in the evenings he went to offer confessions and the eucharist to communists in the Budapest prisons and secretly wrote pastoral advice to Catholic girls under the pseudonym of a female author. In the early thirties, hiding behind the pseudonym of Blanka Seraphini, he wrote a letter to an imaginary little boy preparing for priesthood – himself – who was still running after butterflies and not wearing a reverend. In his letter, he also summarised the beauties and sacrifices of priestly life: ‘you will be a gardener of lilies, a protector of snow-pure lamb souls against a wolf. You will pour new strength into broken hearts, sprout new buds on dead twigs wherever you go and wherever you rise, blessings follow you. . . thou shalt silence the groans, and wipe out the last tears of the dying.’ However, ‘to another, if he struggles a lot, when he returns home in the evening, a faithful spouse waits for him, and the heart of the weary man rests on the bosom of a sweet spouse. . . if you come home exhausted from your daily work in the evening, press down the door handle of your private room, no one will come in front of you, no one will kiss the dust off your forehead. . . You shall not find inward consolation, neither shall ye seek outside.’ Bangha finally gave the warning that ‘a good priest is a triumph for all of us, a bad is a pain for all of us’.[2]

Bangha built a real press empire in a few years, and in this sense was much more decisive in Hungarian public life in the early twenties than Prohászka

The priest no doubt thought of himself as a “good priest,” but opinions on this were divided. Bangha believed in articles and agitation in the daily press, or as an obituary wrote, ‘[If] Ottokár Prohászka brought Hungarian Catholic men into the church, Father Bangha took them out into the streets and organised them into a pillar.’[3] Although, as we shall see, not everyone agreed with the analogy, Bangha built a real press empire in a few years, and in this sense was much more decisive in Hungarian public life in the early twenties than Prohászka. Called a “press apostle” by his followers, Bangha raised money in 1918 for a Catholic press fund (Central Press Company – KSV), which began to function effectively during the counter-revolution, and which included a number of high-volume or major magazines and dailies (Nemzeti Újság [National Newspaper], Új Nemzedék [New Generation], and Gondolat [Thought]). In addition, he himself edited the magazine Magyar Kultúra (Hungarian Culture), although not all Catholic newspapers belonged to him. The Jesuit Heart (Szív), for example, was explicitly critical of the KSV.

From the most modest beginnings, when the KSV’s papers were edited in unheated rooms, in the autumn of 1920 Bangha wrote happily that ‘in the past, our two Catholic newspapers had barely reached one-thirtieth of national newspaper consumption; on the street . . . and today the streets and train stations echo the [paperboys] of [our papers].’[4] His papers appeared in 150,000 copies, approaching the print numbers of some of the largest liberal papers, though not exceeding them. His power in the early Horthy era is well characterised by the fact that when he chastised liberal Christian politician Rezső Rupert in a sermon, Rupert replied: ‘you are the lord of public opinion in Hungary today. . . the whole nationalist jeunesse dorée [rich youth] of the street, the national assembly and the government is politicising according to your taste. . . You own the press, you own the pulpit.’[5]

Even the above data and quotes point out some of the characteristics of Bangha’s personality – and of his press empire. Bangha was a hard-working but often superficial, childish and cynical man who did not seek to build a politically consistent worldview. The central goal of the father was to “fish for souls”, that is, to win as many people as possible for the Roman Catholic Church, which – according to him – could alone offer redemption, and thus save souls from hell. In a series of entries in his diary, he urges himself to preach as much as possible because every day, people who have not been reached and who may not have been rescued from damnation — that is, evangelisation was at the heart of Bangha’s daily thoughts. Bangha placed his worldview under this goal, the central element of which was the struggle against atheist socialism and materialist capitalism, which disintegrated Christian families from two sides. The father appeared to perceive Judaism in the front ranks of both opponents, so between 1919 and 1921 he attacked Jewry with a very significant portion of his writings.

For a time, the latter goal of his was in full harmony with the whole range of awakening (ébredő) or early racist publicists, and his Nemzeti Újság was the main organ of antisemitic propaganda. What Bangha did not want to write, or which could not appear in strictly religious papers, was often given a scandalous, vile, and inciting coverage by the leading opinion formers of the paper, István Lendvai and Lehel Kádár. The duo believed in a “no holds barred” type of antisemitism. In 1921, Kádár demanded “complete social separation” from the Jews: as he wrote, ‘the good Jew must be cordoned off as well.’ Two years later, he explained, ‘just as Negroes have a special place on the tram in America, so should we let the Jews go to a separate fenced place in the theatre and to a separate restaurant. Leave us here in peace, or sew a yellow patch on their clothes as a distinction!‘[6] And Lendvai wrote the following antisemitic poem in 1919: ‘Come oh wind and come oh storm, / kill the Jewish behemoth for us, kill him!’[7]

The radical direction of Bangha’s newspapers has aroused the displeasure of many prominent Catholic politicians and church people

The radical direction of Bangha’s newspapers has aroused the displeasure of many prominent Catholic politicians and church people. Count János Zichy, who owned a majority stake in the KSV, launched an alternative Catholic paper that watched the KSV papers vigilantly, criticized their antisemitism, and pointed out contradictions like when the pope was criticized in Bangha’s papers. The conflict between racial antisemitism – racial protection (fajvédelem), racial theory – and Christianity was evident. In the autumn of 1920, Béla Túri declared, as a Catholic priest and the editor of one of Bangha’s papers, that a Catholic Jew was only a “Christian Jew.”[8] The racialist writer Menyhért Kiss spoke out directly against Catholic priests of Jewish origin: ‘Jews who become Catholic priests often wear a caftan under their reverend.’[9] The far-right, therefore, did not accept baptism as an excuse for the “sins” of Judaism, and in the fall of 1919 the Jewish weekly Egyenlőség (Equality) remarked that there was “no difference of opinion” between them and the far-right, at least in this question.[10] The Zionist Új Kelet in Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoca) similarly reported that baptised Jews were ‘running cowardly out of our crumbling ranks’.[11] However, others did not bother writing articles. In the early 1920s, the names of baptised Jews were posted in front of the Óbuda Synagogue on a sign with the inscription “Traitors”.[12]

Bangha was forced to choose and not surprisingly he went with the traditional Christian viewpoint, opposed to racism. He declared in October 1921 that being an anti-semite was ‘not enough to prove someone’s Christian character’.[13] A month later, he said during a sermon that ‘racial interests are secondary to religious interests. Racial politics is nothing more than pronounced paganism that occurs in primitive Indian tribes as well as in wolves. The baptised Jew is no longer a Jew, and we have no right to prevent him from merging with the Hungarians’.[14] In addition, he even wrote in Magyar Kultúra that Ashkenazi Jews were in fact of Khazar origin, that is, Finno-Tartars, ‘and thus, unfortunately, our sweet, close relatives in terms of blood and origin.’[15]It is worth mentioning that the latter lines were omitted from the works collected by the editors in the 1940s. Behind Bangha’s reluctance towards racialism, in addition to the intention to convert people, there may have been a little-known thing: although the Bangha family of Nagyjóka was a 16th-century Hungarian noble family, Bangha’s paternal great-grandmother had Jewish ancestry. In the anti-Semitic conception of the time, of course, one Jewish ancestor was enough to corrupt a man: as the famous Hungarian racialist writer Lajos Méhely wrote, one who has a drop of Jewish blood, ‘already feels Jewish and acts Jewish.’[16] It is no coincidence, then, that Bangha refused to accept anti-Semitic racial theory, nor is it a coincidence that he never spoke about his Jewish ancestors.

Therefore, in October 1921, Bangha named József Cavallier a chief journalist of Új Nemzedék, then handed over the control of the newspaper to László Szabó, who arrived from the liberal daily Est. Nemzeti Újság was given to Ferenc Bonitz, a previous anti-semite, who now followed Bangha’s more moderate line. The new financial leader of KSV was Dezső Vári, who previously led the office of the liberal Pesti Napló. At the same time, Emil Malcsiner, the editor of Magyar Kultúra started publishing in Pesti Napló. The decision may have been made before the newspapers were “purged”, as in the spring of 1921 the liberal Athenaeum printing house published Bangha’s prayer book, which was then advertised in Est. This was a strange overlapping of liberal and traditional Catholic journalists, unprecedented in Hungarian media history. Perhaps it is not unworthy to note that according to the contemporary Jewish press, Szabó and Vári were Christians of Jewish ancestry (although Szabó later denied this).[17]

The “clean-up” was not well received by the antisemitic journalists. Kádár refused to leave the editorial office at the beginning of October, and in the end Szabó did not take over the paper until the middle of the month. In his first statements, Lendvai vowed revenge on “Seraphinized Salome-Blanka” (an antisemitic wordplay on Bangha’s female pen name) the “Father who is so adept in the Old Testament,” stating that “one Bangha-swallow does not yet make a Jewish summer” (a reference to a Hungarian proverb).[18] What is certain is that Bangha really wanted to see a somewhat less antisemitic line. Kádár later stated that it was Bangha’s explicit request not to attack the Jews and the liberal press.[19]

Bangha’s home was attacked by far-right activists, and the police had to defend the priest and the Pallas printing press

With this move, Bangha became persona non grata in far-right circles. ‘We were fools,’ Lendvai wrote in a furious note at the time, saying that with Kádár, ‘we thought [the antisemitic] cause was important, but I see it is not important to Bangha, it is not important to anyone.’[20] The far-right press put it even more harshly: ‘Who could we accuse of compromise and inconsistency rather than Béla Bangha’ whose ‘path is different from ours […] doing Jewish propaganda?’ The far-right papers also called for a boycott of KSV newspapers, and Bangha received the epithets his ex-publicists had so far only used on his opponents: “traitorous Bangha” “worse than a Jew”, “the left-wing priest”.[21] After his decision, Bangha’s home was attacked by far-right activists, and the police had to defend the priest and the Pallas printing press, which printed the KSV’s newspapers. The violent action of the far-right ébredők did not end there, as in a rally in early November, a journalist from the KSV was beaten up.[22]

Bangha did not fare well after declaring war on his former allies. As an internal Jesuit report found in early 1922, Bangha was hated by everyone: the protestants because he was a traditional Catholic, the Catholics because of his supposed compromises, the racists because he was seen as a liberal, the liberals because they thought he was still an antisemite, and the pro-Horthy government because they thought Bangha was a Habsburg loyalist.[23] Bangha was sent by his superiors to the United States in late 1921 and to Rome in the fall of 1923 to stop him from further tarnishing the reputation of the Jesuit order with his press enterprise, and Bangha bowed his head as an obedient monk before the decision of his superiors. Before leaving for Rome, he wrote an apologetic letter to a far-right press, in which he explained that he had not become a friend of the Jews.[24] However, he had never washed the label off himself, and ten years later Lajos Méhely explained in a complete booklet addressed to the father that while he himself was Makó, Bangha was Jerusalem.[25]

[1] Molnár Antal, Szabó Ferenc, ’Bangha Béla SJ emlékezete’, Budapest, JTMR-Távlatok (2010), 76.

[2] Szerafini Blanka [Bangha Béla], ’A másik. Elbeszélések’, Budapest, Mária-kongregáció kiadóhivatala (1931), 8–9; 14–15.

[3] ’Bangha Béla, a nagy sajtóapostol’, Katolikus Hölgyek Országos Sajtóegyesülete, (1940), 28.

[4] Klestenitz Tibor, ’Bangha Béla jelentése a budapesti nunciusnak a Központi Sajtóvállalat helyzetéről’, Magyar Könyvszemle, (2017), 133, 1.

[5] Világ, (9th October 1921)

[6] Hazánk (1st May 1921); A Nép (22nd February 1923)

[7] A Cél, (1919/4), 216.

[8] As quoted in Új Kelet (30th September 1920), 1.

[9] Zakar József, Fajvédők az 1920-as évek Magyarországán. In: Braham, Randolph L. (ed), ’Tanulmányok a Holokausztról’, vol. 5. Budapest, Balassi Kiadó, (2011), 52-109.

[10] Új Kelet (25th September 1919), 6–7.; also quotes Egyenlőség

[11] Új Kelet (25th September 1919), 6–7.

[12] Zsidó Szemle (9th January 1920)

[13] Budapesti Hírlap, (2nd October 1921), 5.

[14] As quoted in: Hazánk, (6th November 1921)

[15] Magyar Kultúra (1921), 232.

[16] Budapest Főváros Levéltára (Budapest Municipal Archives), VII.5.e.1950.235. 13.

[17] Zsidó Szemle, (21st October 1921), 12. and Tápay-Szabó László, ’Szegény ember gazdag élete’, vol. 3. Budapest, Athenaeum (1928), 157.

[18] Personal papers of István Lendvai.

[19] Bécsi Magyar Újság (6th October 1921), 4.

[20] Personal papers of István Lendvai.

[21] See the following issues of Hazánk: (9th October, 6th November, 13th November, 1921)

[22] Bécsi Magyar Újság, (15th October 1921), 3.

[23] Molnár, Szabó, ’Bangha Béla SJ emlékezete’, 81.

[24] A Cél (1923, October–December), 314.

[25] Méhely Lajos, ’Lassan páter a kereszttel! Bangha Bélának útravalóul’, Budapest, Held (1934), 3.