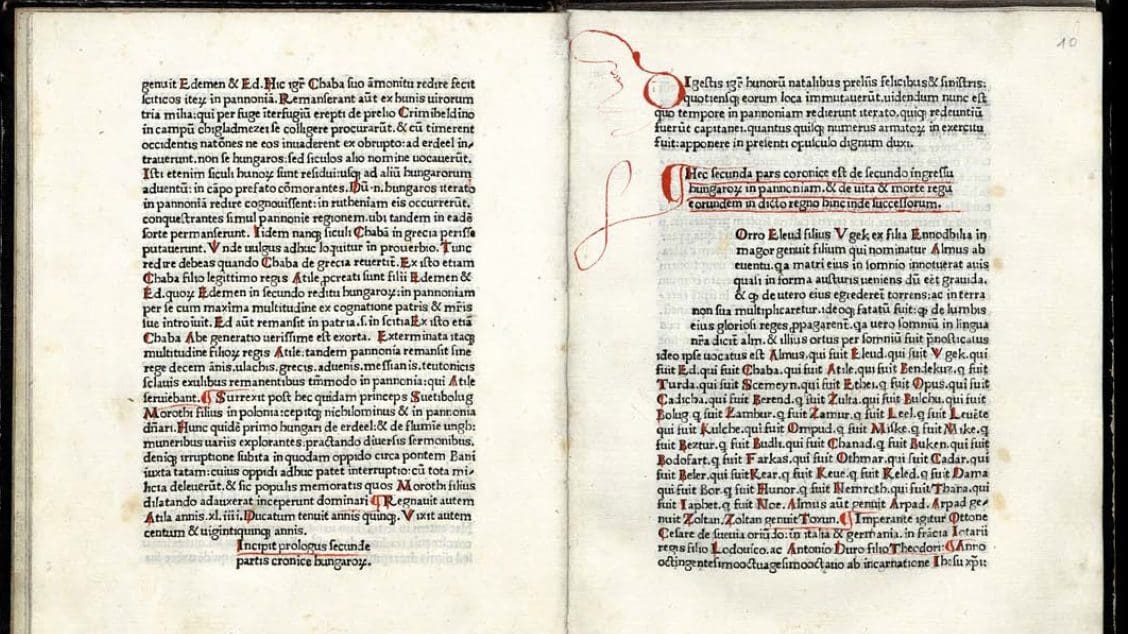

For the 550th anniversary of the publication of the first book printed in Hungary, the Buda Chronicle, or Chronica Hungarorum, this May, the National Széchényi Library published a Latin version of the original copy kept in its collection.[1] The book’s importance is also demonstrated by the fact that, after 1900 and 1973, this is the third time a facsimile of the work is published, and even Pope Francis was given a copy when he visited Hungary this year.

The year 1473 seems incredibly early for printing in several respects, as north of the Nuremberg–Augsburg–Venice line and east of the Rhine–Main line, book printing was not yet feasible at the time. In addition, it was no less rare for a nation’s history to be printed either—

the Buda Chronicle, the first printed book in Hungary by 15th-century printer Andreas Hess, can be considered the second of its kind in the whole world.[2]

Considering all this, it seems plausible to assume that behind the exceptional establishment of the first printing press in Buda, there is not simply the recipient of the dedication at the beginning of the chronicle, i.e. the provost of Buda László Kárai, but also the first man of humanism in Hungary, John Vitéz de Zredna, Archbishop of Esztergom. John Vitéz himself visited the German city of Mainz as well, where the workshop of German inventor Johannes Gutenberg, who introduced letterpress printing to Europe, operated. As the Vice-Chancellor of the Archbishop, Kárai personally invited the German-born printer Andreas Hess from Rome to Buda. Besides, the fact that he also wanted to provide a Hungarian printing house to the University of Bratislava, which was founded at his initiative, may also have played a role in Vitéz’s far-seeing ideas.[3]

The printer spent two years in Hungary, which was necessary since the volume was prepared very slowly over several months—Hess worked without help, thus only three or four pages could be produced a week. On one day, the text of a sheet was taken out, and on the next one, it was printed. Including spoiled copies, approximately 200–250 copies could have been printed, which corresponds to the contemporary norm. At the time, 50–200 copies of German publications and 200–400 copies of Italian publications were regarded as an average number. Exceptions are liturgical books and classical authors such as the record-holder Roman historian and politician Sallust, who by 1500 had appeared in fifty-nine publications.

The chronicle’s introduction says: ‘I undertook the gigantic work of printing The Chronicle of Pannonia which took many days and which, to my mind, must be important to and favoured by all Hungarians.’[4] Nevertheless, we have no data on the reception of the chronicle—the low number of surviving copies, only ten, and the predominantly Central European preservation sites indicate that its influence remained limited, spreading only in this region. Undoubted proof of its contemporary use, however, is that a subject and name index, as well as a list of Hungarian rulers, accompanied the volume preserved in Leipzig, while lines of historical poems were written into the copy of the National Széchényi Library in the 16th century, and that a version of the printed text was also copied in Vienna in 1481.

Books from Buda were difficult to distribute abroad, and in terms of their historical genre, they were not among the best-selling types of publications either. At the same time, Archbishop Vitéz recognised with good sense that the publication of national histories (Nationalgeschichte) in print, and—in case they were missing—their writing was on the agenda throughout Europe. In addition, Vitéz also deserves praise because, after a Spanish story in 1470, the chronicle of the Magyars was the second to be published in Europe, followed by a Czech story in 1475, a French story in 1477, an English story in 1480, and a Danish one in 1495.

Although until the end of the century, twenty-seven thousand publications were printed in over a million copies in about 1,100 printing places in Europe, certain genres, such as historical works, only slowly proved their raison d’être. The beginning of printing was characterised by the publication of handbooks that have been in use for centuries—well-known, ‘classic’ ancient and medieval historical works were published as a rule. However, success could only be expected from those that could be distributed in several countries. Thus, German historian Hartmann Schedel’s work titled Nuremberg Chronicle was published in 1,500 Latin and in 1,000 German copies in 1493,[5] but George of Hungary, i.e. Georgius de Hungaria’s booklet presenting the Ottoman Empire, first printed in 1480, similarly became one of the great bestsellers of the century.

Surprisingly, the Buda Chronicle was considered outdated in its content, structure, and Latin style already in its time,

as it took almost verbatim the text of the earlier Hungarian chronicles, born between the 11th and 14th centuries, with their old-fashioned Latinity. Even if the king was not shocked by this, the humanists around him must have certainly warned him. Andreas Hess, who did not even speak Hungarian, was quite left to his own devices by his environment while printing in Buda—the obsolescence of the text’s language was not his fault at all, but rather of the troubled public situation and events of the time, such as the unsuccessful conspiracy against King Matthias I. Another decisive event was the political downfall of the patron Archbishop Vitéz, who had been in captivity since 1472 and died soon after, which also affected the University of Pressburg, and soon the operation of the complete Hungarian printing press. It is therefore no coincidence that the printer dedicated the chronicle not to the fallen Archbishop or the King, but to Provost Kárai, insignificant compared to the former. King Matthias only gradually recognised the role of printing in the monarch’s propaganda, as evidenced by the fact that he first tried printing anti-imperial pamphlets.[6]

However, the King quickly learned from the mistakes of his previous publications, and soon commissioned one of his legal officials, Johannes Thuróczy, to write another version of the Chronica Hungarorum. In 1488, the first edition of the freshly completed Thuróczy Chronicle was not published in Buda, but in Brünn (Berén in Hungarian, Brno in Czech) in Moravia, which was under Hungarian rule at the time, and then its second edition in Augsburg. In this work, compared to the Buda Chronicle, the intention to idealise Matthias can already be clearly felt. As the introductory recommendation of the Augsburg edition says about the King, ‘your fame and glory shine brightly throughout Europe, because you have so many times put to rout and overthrown the enemies of the Christian people, such as the terrible Turks, and defeated the neighbouring peoples’. In contrast to the Buda Chronicle, which follows the events until 1468, Thuróczy’s work is quite up-to-date as the capture of Wiener Neustadt by King Matthias just a year earlier, in 1487, is already included in it. While there are no pictures in the Buda Chronicle, the Thuróczy Chronicle is richly illustrated with battle scenes and full-length portraits of Hungarian kings. King Matthias achieved his goal by supporting the publication of this work: there are nearly forty copies of the Thuróczy Chronicle only in today’s Hungary, but it also appears in the most distant collections of Europe. It could well be that it was read just as well in Salamanca or Madrid in Spain as in Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

It was only Italian humanist writer Antonio Bonfini who became an even more successful historiographer of King Matthias than Thuróczy, but his work was not published in print until after 1543. Although in addition to the Buda Chronicle, Bonfini follows Thuróczy in the chapters on early history,

the birth of modern Hungarian historiography is clearly linked exclusively to Bonfini’s name.

In his work, ‘the history of the Hungarians becomes an integral part of the history of universal humanity through the universal historical vision that always interrupts the narrative because if humanity as a whole is ignored, Hungarian history also loses its meaning’.[7] For a long time in Hungary, Bonfini’s chronicle was the most widely read Hungarian story. However, not only Hungarians but also the whole world learned about Hungarian history from Bonfini’s printed editions in Latin and from its German and French translations—copies of the work can be found in all major libraries in Europe until this day.

The authors and printers of the chronicles of medieval Hungary all deserve recognition. As a result of their experiments, sometimes better and sometimes less successful, Hungary found its place in world history, and the world learned about the Hungarians.

[1] Chronica Hungarorum 1473, facsimile edition, Gábor Farkas Farkas and Bernadett Varga (eds.), Budapest, 2023. Available digitally: https://oszkdk.oszk.hu/storage/00/00/18/34/dd/1/html/index2.htm.

[2] Béla Varjas, ‘Das Schicksal einer Druckerei im östlichen Teil Mitteleuropas (Andreas Hess in Buda)’, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Vol. 52, 1977, pp. 42–48.

[3] Gabriel Astrik L., The Mediaeval Universities of Pécs and Pozsony. Commemoration of the 500. and 600. Anniversary of their Foundation: 1367–1467–1967, Frankfurt am Main, 1969, pp. 37–50.

[4] Gábor Farkas Farkas, ‘The Buda Chronicles: The First Printed Book in Hungary: Printer, Work, Provenance, Patronage’, La Bibliofilía, Vol. 117, 2015, p. 32.

[5] Schedel also had a manuscript copy of the Buda Chronicle.

[6] József Fitz, ‘König Mathias Corvinus und der Buchdruck’, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Vol. 14, 1939, pp. 128–137.

[7] https://mek.oszk.hu/02200/02247/html/szoveg/bonfini.html, accessed on 2 June 2023.

Related articles: