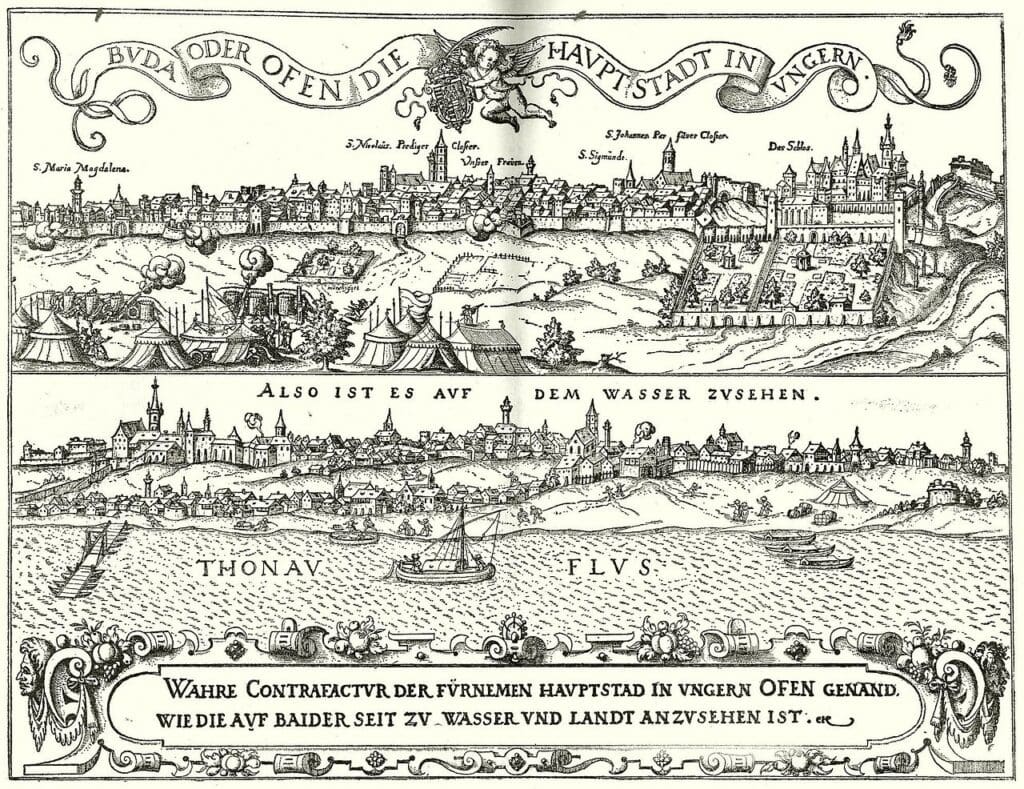

This year Hungary celebrates the 150th birthday of its capital city with various exhibitions, art events, and conferences. Even though the name ‘Budapest’ already appeared on numerous Anglo-Saxon maps from antiquity and in the Middle Ages, it did not exist in this form for centuries. Today’s Budapest was in fact only created on 17 November 1873 by the merger of Pest on the left bank of the Danube and Buda and Óbuda on the right bank.

Nearly fifty former medieval settlements can be identified in the area of today’s Budapest, yet it is almost exclusively the names of Óbuda, Buda, and Pest that appear in Hungarian and foreign narrative sources. This is no coincidence, since the mention of Óbuda is justified by the existence of royal ecclesiastical institutions from as early as the 11th century onwards, as well as by the saga of Attila, King of the Huns, associated with the Roman ruins. In the case of Pest, it was due to its economic importance and the diets held on its outskirts that its name was written down in chronicles. While Buda, founded later, in the 13th century, soon became the political centre of the country, for a long time it was the crowning city, Alba Civitas (today’s Székesfehérvár), where the country’s governance was concentrated.

The early sources of the 11th and 12th centuries are of course silent about Óbuda (literally meaning ‘older Buda’) and Pest. Both settlements are recorded as important Danube crossing points by the anonymous chronicler of King Béla III of Hungary in his work date to between 1200 and 1220. In it, he described how Prince Árpád, who led the Hungarian Conquest, and his chieftains, marched into the city of King Attila the Hun after crossing the Danube, where they admired the royal palaces, some of which had survived intact.[1] These words, of course, could have been referring to the ruins, including amphitheatres, that survived from Roman times and can still be seen between Buda and Aquincum.

Thanks to the Nibelungenlied, Óbuda is extremely well-known in the Attila saga. According to later German sources, Attila was buried in Óbuda and he also killed his brother Buda there after he named the town after himself against his brother’s will: this is the earliest etymology of the names ‘Óbuda’ and ‘Buda’.[2]

The heyday of medieval Buda began after the Mongol invasion of 1241–1242 when King Béla IV founded Buda and its castle.

In his letter to Pope Innocent IV in 1250, the King called the Danube the water of resistance and underlined his intention to fortify the Danube with castles to protect the country and Europe itself against another pagan attack. The gem of these Danube fortresses undoubtedly became the King’s most important construction, the Buda Castle.

The buildings in Buda themselves also started to attract the attention of contemporary chroniclers, thus the Assumption Church of Our Lady (today’s Matthias Church) was the first of the edifices in Buda to be aesthetically commented upon, having been described as ‘beautiful’ (‘schoene Munster’) by an Austrian chronicler. After 1301, with the accession of the Angevin Dynasty, Buda gradually became the most important city in the country. From the 15th century onwards, the church of Buda was not simply the parish church of the city, but the most prestigious church of Buda and a place of great importance for court and city festivities, diplomatic receptions, royal weddings, the presentation of kings after they acceded to the throne, and the entrance of kings and queens (‘joyeuse entrée’). Also, it was the place where the flags captured from the enemy after campaigns were flown.

The town usually appeared in contemporary travelogues, too. For the famous Burgundian traveller Bertrandon de la Brocquière, it was already clear that Buda was the country’s capital when he visited the city in April–May 1433.[3] He pointed out the great palace built by King Sigismund, the so-called ‘Fresh Palace’, which was, however, still under construction when the author visited the country. He was right that the ‘Fresh Palace’ has indeed impressed contemporary travellers, from Pedro Tafur of Spain to Hans Seybold of Bavaria. When visiting the city in 1502, accompanied by the Hungarian Queen Anna de Foix, he wrote the following: ‘Lunch was held in one of the largest and most magnificent halls in the world, everything glittering with gold and silver.’[4] Like so many other travellers, Bertrandon also drew attention to the sulphurous hot springs of the Buda side. He was attentive to the internationalism of the bourgeoisie, although seeing clearly that the Germans outnumbered the Hungarians in numbers and importance in the judiciary, commerce, and industry. He described the city as the centre of trade in Hungary, and he also paid attention to the French-speaking Jews who had been expelled from French soil. Besides, he observed that King Sigismund, on his visit to Flanders, had noticed the carpet industry there and thus invited craftsmen to the country. The traveller was fascinated by the beauty of the Buda hills, where the citizens of Buda cultivated grapes.

After the palace of King Sigismund, but especially after the great construction works of King Matthias, Buda’s number one landmark became the Royal Palace with its library, the Bibliotheca Corvina. Matthias himself also regarded the library as a powerful tool of courtly representation, and he was not to be disappointed. Not only in his lifetime, but even decades after the Turkish occupation, the library was a must-see for travellers, or at least was mentioned in their descriptions.

In 1526, the news of the defeat at the Battle of Mohács and the impending Turkish siege caught the commanders of the Buda Castle completely unprepared.

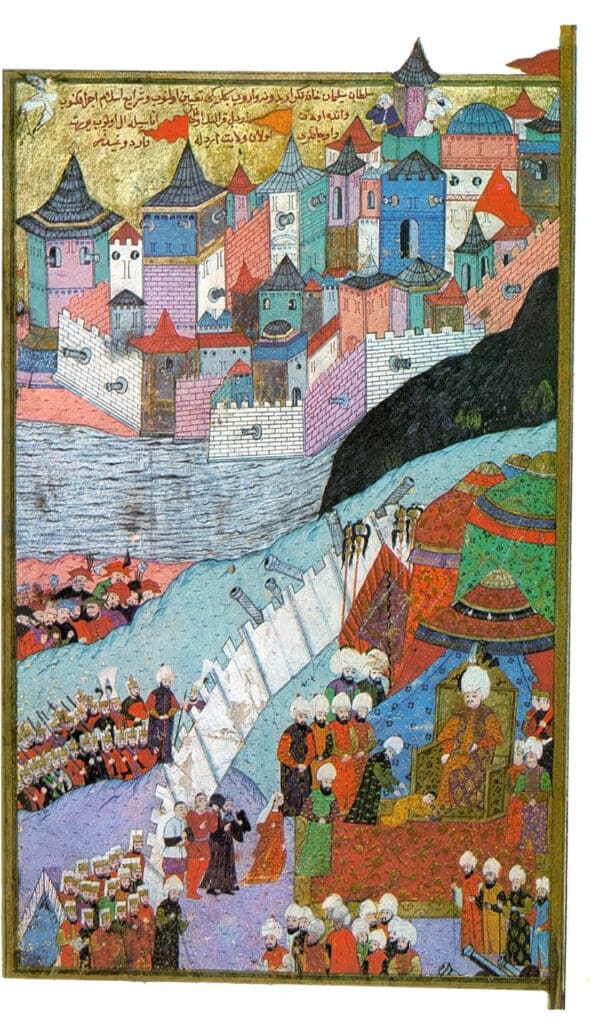

The castle’s garrison and a good part of its artillery were sent into battle, leaving no chance of a successful defence. Queen Mary, the widow of Hungarian King Louis II who had died in the battle, decided to flee. The Turks took possession of the town and castle without a fight and burned it down. According to the chronicler of Sultan Murad II, Buda was ‘a very great and ancient city…with its indestructible castle, it is one of the wonders of the world. Between its walls no enemy has ever set foot, nor has it ever been overrun…’ In his description, the Sultan’s arrival turned the area into a rose garden, and he also mentioned that from the ‘beautiful palace of the evil king,’ a lot of booty was loaded on board their ship, including two large cannons, which John Hunyadi had captured at Belgrade in 1456.[5] Candelabras, which tradition has it came from the Assumption Church of Our Lady in Buda, were also taken to Constantinople as spoils of war, which can still be seen today in the Ayasofya Mosque, the former Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. The Jews who remained in the city were resettled in Thessaloniki by the Turks.[6]

After 1526, the war events quickly escalated, and the city suffered several sieges in the following years.[7] On 29 August 1541, on the 15th anniversary of the Battle of Mohács, the city was effectively occupied without a fight, and held by Turks for centuries, with a trick. What happened was that the Turks marched seemingly peacefully to the castle to visit Buda, as if they were tourists. However, on the orders of the Janissary leaders, the weapons of the citizens of Buda were confiscated and the city’s strategic points occupied, in particular the gates. Buda was made the centre of a new province, the Buda Vilayet, and a new Pasha of Buda was immediately appointed as well. On 2 September, from the tower of the Assumption Church, it was already the singing of the muezzins that could be heard, summoning the Turks to prayer. The city was not recaptured by Christians until 1686. Eventually, Buda’s role as the ‘Bulwark of Europe’ was inherited by later Hungary, already in Christian hands and under Habsburg rule.

[1] János M Bak, Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy (eds.), ‘Anonymous, Notary of King Béla’, The Deeds of the Hungarians, Budapest–New York, 2010, pp. 98–102.

[2] László Veszprémy, ‘Buda in Medieval Historiography: Etzilburg. Sicambria, Óbuda, Buda’, in Irena Benyovszky (ed.), Towns and Cities of the Croatian Middle Ages, Zagreb, 2017/2018, pp. 253–263.

[3] Galen R. Kline (trans., ed.), The Voyage d’Outremer by Bertrandon de la Broquiere, New York–Bern, 1988, pp. 151–157.; Balázs Nagy, ‘The Towns of Medieval Hungary in the Reports of Contemporary Travellers’, in Derek Keene, Balázs Nagy, and Katalin Szende (eds.), Segregation, Integration, Assimilation. Religious and Ethnic Groups in the Medieval Towns of Central and Eastern Europe, Farnham, 2009, p. 177.

[4] Antoine Le Roux de Lincy (ed.), ‘Discours des Cérémonies du Mariage d’Anne de Foix’, Bibliothèque de l’École des Chartes, Vol. 22, No. 2, 1861, p. 434.

[5] Kemalpaşazâde, also called Ibn Kemal, Ibn Kemal Paşa, or Şemseddin Ahmet ibn Süleyman ibn Kemal Paşa (d. 1534), XXX, 114–115, in Hungarian translation József Thury (ed.), Török Történetírók, Vol. I, Budapest, 1893, pp. 255–256.

[6] Géza Perjés, The Fall of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary: Mohács 1526 – Buda 1541, Boulder, 1989.

[7] László Veszprémy, ‘Buda: from a Palace to an Assaulted Border Castle of Europe (1490–1541)’, in Balázs Nagy, Martyn Rady, Katalin Szende, et al. (eds.), Medieval Buda in Context, Leiden, Boston, 2016, pp. 497–512.

Related articles: