Social policy, contrary to what Marxist historians claimed about the interwar right-wing Horthy-period, was not an alien concept to the Hungarian right. Few people saw the middle-class issue as László Gyöngyösy, a Calvinist writer of Transcarpathian origin, did, who in 1921 wrote that the middle class was being reorganised, with new rich and new poor masses created every day: ‘a new, more viable society is being formed. Let the rotten fruits fall, they cannot be prevented from falling with artificial means anyway’.[i] But the government did, in fact, seek artificial solutions, attempting to change the social order through forcible redistribution. For example, István Weis, a member of the Christian Socialist Party, who was appointed secretary of the Ministry of National Welfare under the Teleki government, was convinced that ‘Bolshevik social policy’ had ‘surpassed that of the liberal capitalist states’.[ii] His musings on the subject reflect the wider dilemma of the contemporary right: could certain tenets of Socialist social policy be borrowed in order to serve right-wing goals?

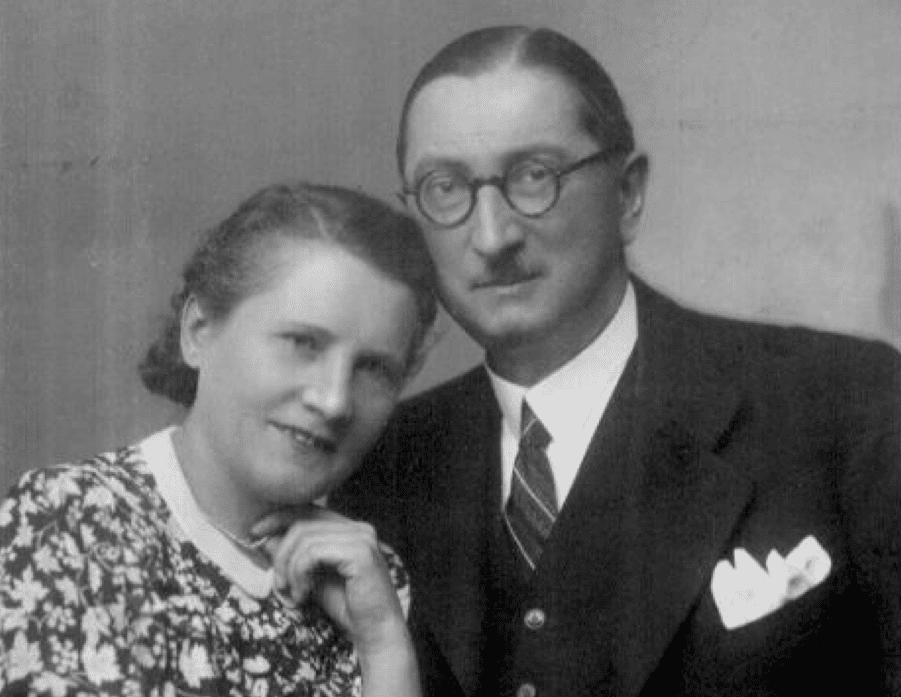

Weis was born into a middle-class, intellectual family in Munkács, Transcarpathia (today: Munkachevo, Ukraine) on 10 July 1889. His father was a judge, coming from a family of German ancestry. After graduating from law school, he joined the Ministry of the Interior as a clerk in 1912. As his biographer, Éva Petrás notes,[iii]during the 1919 Soviet Republic, he was arrested and even sentenced to death for counterrevolutionary activity, a sentence which was obviously never carried out. After Miklós Horthy came to power, he first returned to the Ministry of the Interior, and from 1921 he worked at the Ministry of National Welfare.

‘[They] must lead and follow the beautiful example of the privileged classes of 1848’ in ‘renouncing their interests’

In 1922 Weis published several articles in the columns of the right-wing journal Szózat in which he wrote that because of ‘[Austrian] oppression’ in Hungary ‘certain factors’ were ‘favoured too much at the expense of the majority, [and] did not meet the demands of social justice, and even to some extent the requirement of the preservation of the Hungarian people’, and that his aim was now ‘to build up the Hungarian state to remedy all these problems’.[iv] While this might sound antisemitic—and Weis was certainly inclined in that direction—the ‘certain factors’ here meant not only the Jews (‘the big capitalists with their internationalist tendencies’) but also the big landed gentry: according to Weis, ‘[they] must lead and follow the beautiful example of the privileged classes of 1848’ in ‘renouncing their interests’. Weis promised the needs of the masses ‘will be satisfied, unjust advantages will be abolished’.

He continued thus: ‘The course of national democratisation cannot be obstructed by a liberalism which… compromises with the traditions and needs of feudal social order and is the hotbed… of the excesses of the capitalist order of production. Democracy without liberalism should be our slogan at a time when the individual and his rights must be dwarfed by the whole; liberalism without democracy is the death of Hungary.’

The approach of Weis to welfare, an attitude that in fact prevailed under the Teleki government, was therefore not only sensitive to social issues, but also subscribed to the idea of an ‘anti-capitalist democracy’, and also to ‘progress’ and ‘social justice’:

‘[The upper classes] must renounce the representation of the interests of the social class from which they come: they must stand under the banner of progress, of the rights of the people. The greatest Hungarian politician of all times, Lajos Kossuth, saw with the certainty of a genius that the Hungarian nation would be ruined if social progress and the national ideal were opposed to each other, if we could not bring our national aspirations into line with the spirit of social justice.’[v]

‘The Christian national idea in politics means…repairing the consequences of the destructions caused by the materialism of the nineteenth century’

In another article, Weis also explained that, as a Christian socialist, he was not opposed to Marxist theses because ‘the Christian socialist agrees with the Marxist in regarding today’s society as evil and the distribution of social goods as unjust’.[vi] Weis, in fact, was not alone with his views in the Hungarian state apparatus. Gyula Altenburger, a university lecturer and adviser to Pál Teleki, dreamed of ‘eradicating’ capitalism, and wrote that ‘we could not reasonably raise any objection to social democracy, on the contrary, everyone should join it’, provided that it was Hungarian nationalist in character.[vii] Prime Minister Teleki himself said that ‘the Christian national idea in politics means…repairing the consequences of the destructions caused by the materialism of the nineteenth century, liberalism and capitalism, and especially by their overgrowth. It is necessary to ensure that Christian Hungarians…occupy the places they deserve in economic life and elsewhere.’ To this he added that ‘we must decide whether we will choose the right-wing Christianity of Ottokár Prohászka or remain in the service of liberal capitalism’.[viii]

And this is how Nándor Bernolák, soon to be Minister of National Welfare, spoke in Parliament in September 1920: ‘It is the idea of social justice which alone is capable of restoring social peace to the country, which [breaks down] […] the outgrowths of capitalism […] in the economic liberalism which […] lacked the sense of social justice that would have led humanity towards social equality.’[ix] However, it was István Haller, the Christian Socialist Minister of Education, who was primarily responsible for the policies aiming to uplift the middle class, and he stated most clearly that ‘the Communists have no right to expropriate Marxism.’[x]

The Communists certainly didn’t agree, and they put Bernolák as well as Weis on trial after World War II. Petrás writes that Weis was interned twice and then sentenced to prison in a show trial. His ordeal did not end with the death of Stalin, and he remained under arrest and in prison until 1954. He worked as a night guard until 1963 and lived off his meagre pension until his death in 1973. The curious views of Weis and the experiment of the Hungarian government in the early twenties to establish a right-wing social policy are valuable food for thought in considering the dilemmas of a proper conservative approach to capitalism and social justice.

[i] Magyar Helikon, II. vol. (1921), 586.

[ii] Éva Petrás, ‘Weis István, a „javíthatatlan, semlegesíthetetlen, örök ellenség”’, Betekintő, 2013/3, http://www.betekinto.hu/2013_3_petras, accessed 4 November 2022.

[iii] Petrás, ’Weis István’.

[iv] Szózat, 28 Jan. 1922.

[v] Szózat, 20 June 1922.

[vi] Szózat, 3 March 1922.

[vii] Gyula Altenburger, Levelek a magyar nemzethez!, Budapest, n. p., 1918, 87-88., 99.; A Cél, 1919/1, p. 2, 5.

[viii] See online: http://mek.oszk.hu/10300/10338/10338.htm

[ix] Nemzetgyűlési napló, 1920, V. vol., 259.

[x] Szózat, 22 Jan. 1922.