The image of Christianity as a large and solidary family contributed decisively to its rapid and overwhelming spread already in the first centuries AD.[1] As it was put later, Christians were united by the res publica Christiana, the international community of Christian peoples, which empowered them to give a proportionate response to the threat of an external hazard—and, within the framework of the ideology of the crusades, they could do so either individually or together with their rulers based on the authority of the Pope. Those who evaded the obligation of the crusades, the fulfilment of which was also supported by the Pope with spiritual and then financial privileges from the 11th century on, implicitly jeopardized their own salvation. Of course, the reception of the appeals always depended on the political circumstances of the given period, even if, according to the Church’s understanding, the Pope’s appeal carries as much weight as the words of St Peter or Christ Himself.

Similarly to the rulers of the time, the papacy did not have immediately mobilizable currency reserves or armed forces either

—they based their planning on voluntary offerings and particularly on future special taxes to be imposed on the clergy or laypeople, or sometimes both. The best-known example of such levies were the so-called Saladin tithe, or the Aid of 1188, collected in England and France after the loss of Jerusalem, and from 1199 onwards, the papal income tax, amounting to one-fortieth of all church revenues in certain years. In addition, the redemption of crusader-vows also mobilized a large amount of cash.

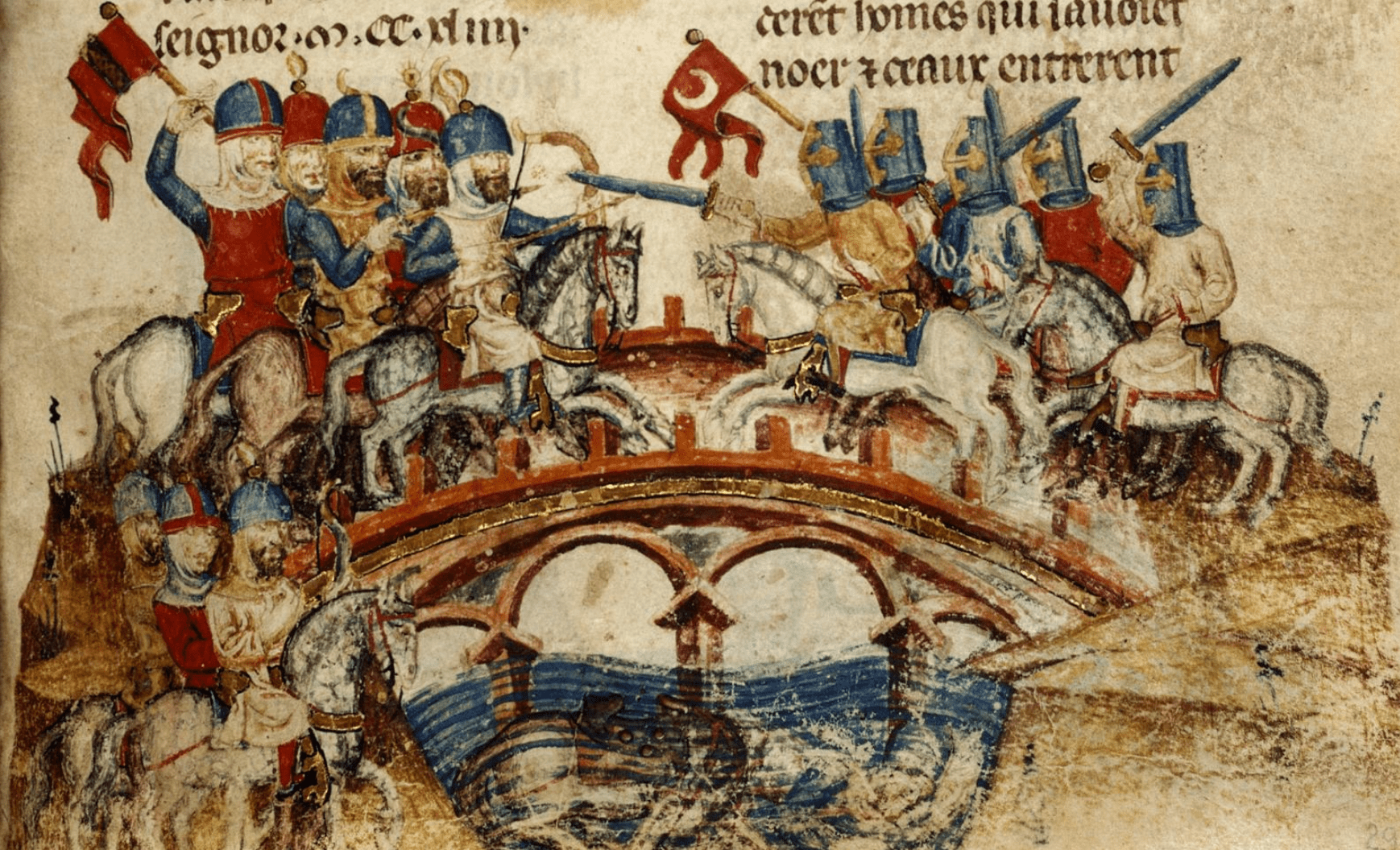

Undoubtedly, the community of Christian nations functioned well and has achieved remarkable results under the umbrella of the crusader ideology since the 11th century. In Europe, great masses were stirred to reconquer the Hispanic peninsula, and the crusading ideology kept the Latin states of the Holy Land alive until 1291. Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean, from the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Azov, the contours of a Latin world emerged, which, thanks to the Italian trading cities, the Franks, the Aragonese kings and the Johannites, remained viable until the Ottoman conquest in the 16th and 17th centuries. From the 12th century, the Baltic region was also added to the picture, where the military orders of the crusades similarly expanded the borders of Latin Christianity in battles that enjoyed pan-European support.

The Hispanic Reconquista gained new momentum in 1063, when Pope Alexander I announced what can be considered a proto-Crusade, which ended with the successful recapture of the Aragonese town of Barbastro the following year. Jumping ahead of the 13th century, it was in the 1230s that King Ferdinand III of Castile, later revered as a saint, ended Moorish rule in the central part of the peninsula. In 1236, he captured the old Umayyad capital, Cordoba, and then took possession of Seville in 1248, which was the grand finale of his conquests. Similarly, after several years of warfare, James I the Conqueror, King of Aragon, the husband of a descendant of the Árpád dynasty, occupied Valencia in 1238, after receiving the Papal bull proclaiming the crusade from Pope Gregory IX a year earlier.

Meanwhile, the Baltic Crusades did not stop either, although they had variable outcomes. In September 1236, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, entrusted with crusader privileges, suffered a decisive defeat at the hands of the pagan Samogitians in the battle of Saule (which, it is important to note, has been the Remembrance Day of Baltic unity from 2000). In the spring of 1242, the Novgorod militia led by Alexander Nevsky, later revered as an Orthodox saint, also defeated the troops of the Teutonic Knights on the frozen Lake Peipus (Chud).

At the time of the appearance of the Mongols, the Christian world was at war all over the world with the Muslims

and all those who opposed the papal power, whether they were heretics, Orthodox, or the German emperor himself. Although the privileges were applicable to those who fought in the Holy Land, they could be earned for pursuing any of the above purposes based on papal decision. So, in the 1240s the Mongols were in fact not the only or the most important threat to the Christian world, even if their cruelty and unexpectedness terrified contemporaries.

The news of the Mongol onslaught on Eastern Europe only slowly crossed the sensitivity threshold of the contemporaries in the West: although they had known about it drawing close well in advance but had not appreciated its severity. Reflecting on the topic of this article’s title is all the more justified, as the notion that the Christian West failed Central Europe, and in particular the Kingdom of Hungary that suffered the greatest destruction, has been constantly present in popular literature in connection with the Mongol expansion. In the longer run, this opinion was also extended to further crucial events in medieval Hungarian history. Thus, according to this view, at the siege of Belgrade in 1456, during the fight against the Ottoman Turks, the help of the Western crusaders arrived late, just as it did not reach the decisive Battle of Mohács against the Turks in 1526. The truth is that Christian solidarity was in play in these cases as well, only its effectiveness and timing are questionable—in 1526, the English royal court was surprisingly up-to-date on the events of the Hungarian battlefield, and in addition to the actual papal financial aid, the promised English aid also arrived, albeit only after the battle.

Something similar happened in 1241, when in the spring of that year the Mongols under Batu Khan (1227–1255) attacked Hungary and destroyed the royal army[2] in the Battle of Muhi on 11 April 1241. The king himself, Béla IV (1235–1270) could hardly escape—the Mongols kept pursuing him so he was forced to wait for them to leave the country on an island in the Adriatic Sea until the spring of 1242. He expected help from the rulers of the surrounding territories in vain, as the Russian princes had already been defeated, the Polish prince had been killed by the Tatars, the Czech king had retreated, and, instead of helping, the Austrian prince tried to exact revenge on the Hungarian king for previous grievances. The Hungarian king, the primates and monks sent letters one after the other to the Western royal courts and the Pope asking for help. The Hungarians mentioned the lack of solidarity in their letters several times already back then—they rightly felt that they had been left to their own devices, and even betrayed. In fact, the behaviour of the Austrian prince was not far from the latter.

The question is what kind of help could the Hungarians have hoped for?

In his letter sent to Rome in May 1241, the Hungarian king asked for ‘advice and protection’, which Pope Gregory IX (1227–1241), who generously issued bulls of the crusade, comprehended. On 16 June, the Pope granted those fighting against the Tatars in Hungary the same privileges as pertained to the crusaders in the Holy Land, and three days later he called on the superiors of the German and Austrian Cistercian, Dominican and Franciscan orders to proclaim a new crusade. Of course, the reply of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (1212–1250) must have sobered Béla IV up: in his letter, he listed his reasons why he could not take part in such a campaign, but left the possibility of his son, Conrad IV, chosen King of Germany (1237–1254) fighting open.

Until the work of Peter Jackson, Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at Keele University, was published, the details of the reactions of the papal court and the German emperor had not been widely known.[3] With that knowledge, however, a relatively data-rich tableau is placed before us. Surprisingly, when the news of the Mongol invasion broke in Germany, in the absence of the Emperor and his son, Siegfried, the Archbishop of Mainz, convened a synod in the city of Erfurt almost immediately, even before the papal deliberation, where a decision on launching a crusade was made and announced in the ecclesiastical provinces on 25 April. King Conrad himself took up the cross, too. Among those who joined, were the Czech King, the Archbishop of Cologne, the Duke of Braunschweig, and the Count of Tyrol. Preparations were under way in Saxony as well, and the Worms yearbook also reported on the redemption payments being collected. Nuremberg was designated as the assembly station for the army on 1 July 1241, but in the end, it never set off. It was never clarified, however, where the Western army wanted to protect the borders of Christianity: at the Alps or at the border of Hungary and Austria. Several sources indicate that the purpose of the campaign was to stop the advancing Mongols, and not to deploy the army in Hungary—according to a letter from King Conrad, it was only necessary to fight in case the pagans crossed the German, Czech or Polish borders.

Today, we can only guess the reason for the failure of the campaign. Perhaps the renewed local civil war can be blamed, or, to a greater extent, the neglecting of the Pope on the part of the German bishops and King Conrad: by placing the campaign under their own leadership, they seriously violated the rights of the Pope.

The antagonism between the Pope and the Emperor put into question the ecclesiastical legal basis and framework of the crusade,

as secular rulers may have prepared a campaign, but the actual launch of it and the proclamation of the indulgences related to the campaign were exclusively the rights of the Pope. The fact that Frederick II regained the Holy City while being excommunicated in 1229 did not change any of the ecclesiastical legal principles, and from the very beginning, it put in doubt that he would once again undertake a similar ‘ungodly’ crusade.

To complicate matters further, the conflict between Frederick II and the Pope culminated in these years, and in February 1241, the vows taken for the crusades in the Holy Land could be exchanged for entering a war against Frederick. At the council held in Rome at Easter 1241, the Pope planned to strip Frederick of his title of Emperor with the help of the primates who supported him. However, in a way that was quite unheard of, the emperor’s men first prevented the primates coming from across the Alps from reaching Rome on land, and then on 3 May, they attacked and captured the ships carrying the primates who were trying to get to the council by sea, thus thwarting the start of the council.

Then the worst thing that could happen materialized: Pope Gregory IX died in August 1241. Thus, the Papal throne became vacant, and the question of the crusade was taken off the table once and for all.

To sum up, the defence mechanism of the Christian world was triggered incredibly quickly in 1241, but due to various conflicts of interest, mostly international, it slowed down just as quickly and then became totally paralyzed.

Of course,

the defeat suffered by the Mongols also had some positive effects on the future Hungarian foreign policy strategy.

The lack of Western aid made the Hungarian royal court aware of the interdependence of the Central European states, and in the thinking of Hungarian decision makers, it contributed to the birth of a very early Central Europeanism, the first Hungarian formulation of the idea of the ‘bulwark of Europe’ (antemurale christianitatis).[4]

[1] James C. Russell, The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity: A Sociohistorical Approach to Religious Transformation, New York, Oxford University Press, 1994.

[2] Attila Gyucha, Wayne E. Lee and Zoltán Rózsa, ‘The Mongol Campaign in Hungary, 1241–1242. The Archaeology and History of Nomadic Conquest and Massacre’, The Journal of Military History, Vol 83, No 4, 2019, pp. 1001–1021.

[3] Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410, London-New York, Routledge, 2018, pp. 69-75.

[4] Grischa Vercamer, ‘The Mongol Invasion in the Year 1241 — Reactions among European Rulers and Consequences for East Central European Principalities’, Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung, Vol 70, No 2, 2021, pp. 227–262.