Ispáns—leaders of the castle district with a fortress and royal lands attached to it—have been in existence in Hungary since the Middle Ages, but due to the re-introduction of the title of the főispán (literally chief-ispán), we now confine ourselves to the twentieth-century history of this office, including the period of the crackdown and liquidation of főispáns (1944–1950).

The word may sound foreign today, so it is worth clarifying its meaning at the twilight of the institution. The Hungarian administrative units (counties, or vármegyék) and the cities with the right to legislate were headed by the főispán, whose powers also extended to the state authorities, the military authorities, the officials, and the legal authorities (municipalities).

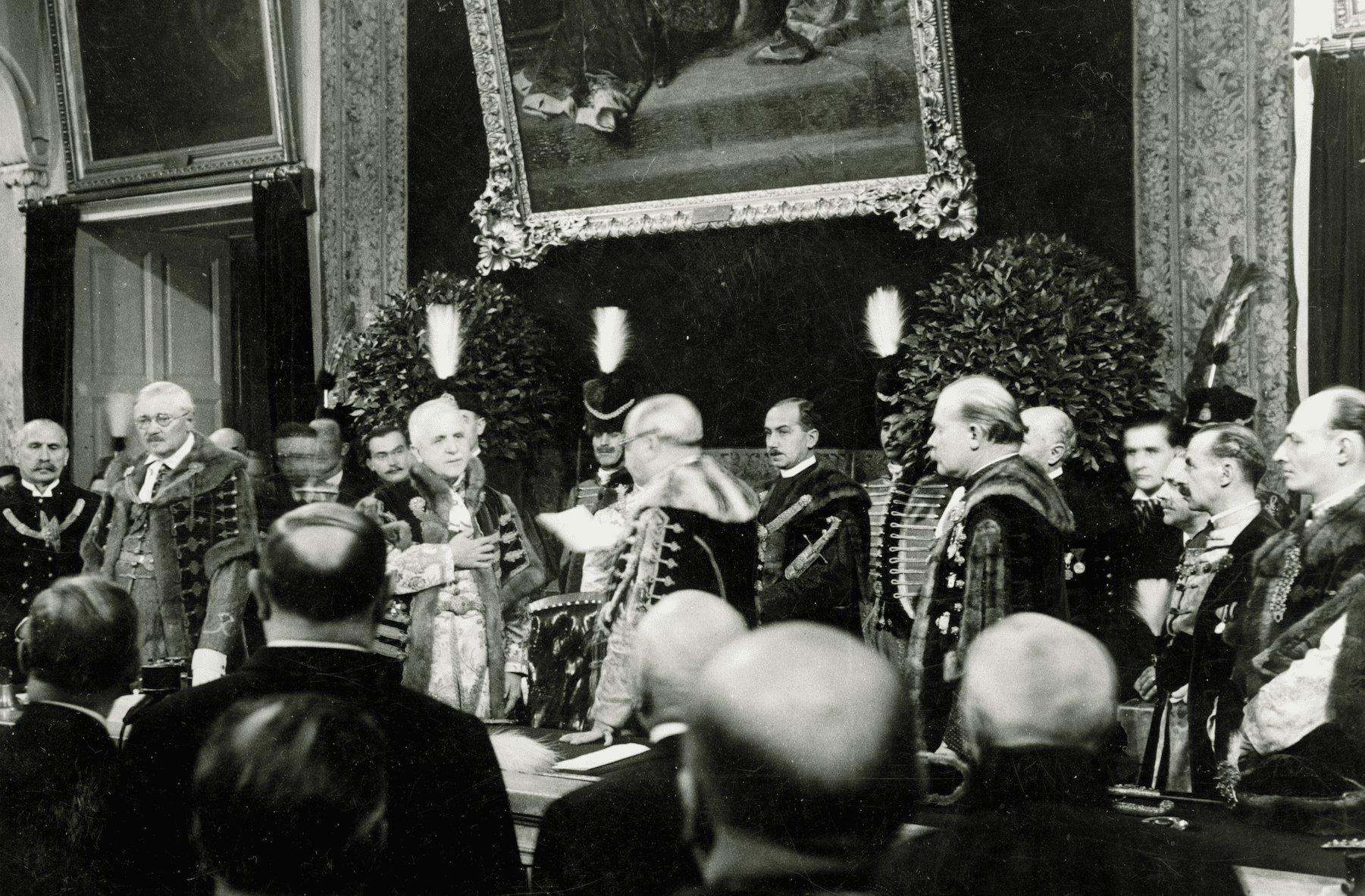

The főispán exercised full control over the representatives of the legislature

The főispán exercised full control over the representatives of the legislature. However, the főispán was not a representative of the legislature but of the central government, who checked that the operation of the legislature was consistent with the government’s policy and that the government’s instructions were being carried out in the county. The főispáns were appointed by the head of state, but their position did not require any professional training. Some other bureaucrats, such as the szolgabíró, were subordinate to the Chief Lieutenant, while the alispán (literrally sub-ispán) was the first person in the county administration, elected by the General Assembly from among the four candidates for the főispán.[1]

From the description above we can understand why this position was so coveted by those seeking to control the country – among them the Nazi occupiers of 1944 and the Communists.

It is obvious that without coercion, no Hungarian chief was elected sovereignly after 19 March 1944. The German occupation influenced the process, even though the signature was ultimately given by Miklós Horthy. German sources show Nazi pressure primarily came to replace főispáns, while less high-ranking posts were rarely dealt with.

German Imperial Commissioner Edmund Veesenmayer was able to report to Berlin on 28 Apil that ‘as a first result of the struggle to replace the főispáns, 19 főispáns had now been removed. […] I’ll demand the replacement of more főispáns in a few days. More resistance can be expected from the governor [Horthy].’[2]

On 11 May, he could already report that ‘the clean-up of the Hungarian rural administration is progressing satisfactorily. So far, 41 főispáns have been removed and 38 főispán positions have been filled, with three more seats vacant; as there are 62 főispán positions in the Hungarian rural administration, of which 41 are county and 21 are urban ones, so the number of newly filled főispán positions exceeds two-thirds of all, because in some cases the counties and the cities are headed by the same person.’[3]

The collaborationist Minister of the Interior Andor Jaross recalled in a confession attached to a People’s Tribunal case, ‘[…] in connection with the appointments of a főispáns, I had in mind the goal of appointing only an individual who was a National Socialist or a sympathetic to the idea.’[4] But he was not entirely successful as some főispáns were, in fact, not of very much help to the occupiers.

Many anti-Nazi főispáns had already resigned after the German occupation, for example, Miklós Beliczey, Ödön Inczédy-Joksmann, Béla Bethlen and Ferenc Kölcsey. The latter told Jewish families in Szatmárnémeti (Satu Mare, Romania today) that he believed deportations were being planned. He allegedly believed that the German racial programme would not have spared the Hungarians in the end: ‘They will take you first, then us.’ He finally resigned in April.[5]

Not everyone was a collaborator among the new appointments or those who remained in place. Péter Schell, the főispán of Kassa (Kosice, Slovakia today) was left in the position, where tried to free veteran Jews from deportations, and later he took over the interior ministry in the Lakatos government, which was preparing for the exit from the war. He was eventually deported to Buchenwald following the Arrow Cross coup. Mihály Nikolits, the főispán of Pécs, expressly refused to convene a deportation briefing for administrative officials scheduled for 22 June. In a letter to Jaross, he refused to take responsibility for a policy ‘that goes against these convictions.’[6]

Not everyone was a collaborator among the new appointments or those who remained in place

But there were also collaborators. József Piukovich, the new főispán of Bács-Bodrog county, arrested his predecessor, Leo Deák, who had previously protested against the massacre of Jews in Újvidék in 1942. In light of this, it is outrageous that after the war, Deák was abducted from his apartment in Budapest by Yugoslav partisans, then tried in Novi Sad and finally executed in November 1945. On the other hand, József Piukovich, the collaborating főispán who handed over Deák to the Gestapo, received just ten years in prison in Hungary.

And if the Hungarian civil servants could not expect fair proceedings before some Hungarian people’s courts, trials in the neighboring states were even worse. Béla Bethlen was not spared by the Romanian People’s Tribunal because, although he resigned after the German occupation, he had previously been involved in the administration of Northern Transylvania, thus remaining responsible for the “disintegration” of Romania. Bethlen was sentenced to three years of forced labour and lived as a simple labourer afterwards.

Some főispáns did not help themselves with their testimonies at the People’s Tribunals. This was the case of László Mérey, főispán of Pest county, who testified that his attitude towards Germans was to ‘give them not more than what they demand from us’. If Mérey had really done just that, it would not have helped his cause, as giving 100 per cent was just enough to carry out the Holocaust. In addition, he even added that ‘I was not in a position to’ oppose the implementation of Jewish laws, as it was the job of the government to hold the administration accountable for the implementation of the political program of the current government, the Sztójay government. ‘Of course all protests would have been fruitless.’ His testimony is incomprehensible, as he did, in fact act against the deportations, personally hid Jews who later testified for him in court, protested against the German gendarmerie, stood up against the Arrow Cross, held the alispán accountable, and protested about the deportations with Horthy. In the end, Mérey did not harm himself, as he was acquitted by the National Council of the People’s Tribunals (NOT).[7]

‘All Jewish property is national property, and therefore all aforementioned excesses have to be stopped even by force, and must be reported to me’

The complicated situation of Mérey is illustrated not only by his trial proceedings but by primary sources as well. For example, on 19 May 1944, he told the mayor of Vác, Kálmán Karay Jr. that ‘all excesses by German military groups or soldiers – theft, pillaging or violence – is explicitly forbidden. All Jewish property is national property, and therefore all aforementioned excesses have to be stopped even by force, and must be reported to me.’ Mérey demanded “retribution” against soldiers who went overline.[8] Mérey’s tone could not have been philosemitic, and in his official notes he employed the pro-German attitude prevalent at the time. On 30 May, he told the local mayor to cordially invite German officials for celebrations and also claimed that the ‘order and peace’ of the country are ‘most important’ due to the nearing front lines.[9] Yet on 10 June, he told all local főszolgabírós that training courses organized by the Arrow Cross for their own leaders ‘had to be stopped’ by all means.[10]

In addition to them, a number of főispáns were held accountable for their alleged or actual sins in the People’s Tribunal. After the Soviet occupation, the office was retained for some time, so it is possible to come across old articles explaining that ‘Communist and Social Democratic főispáns were appointed.’[11] However, a press campaign was soon launched, which depicted főispáns as aids of the capitalistic oppressors.

Finally, the use of the inhered title of főispán was banned by law in 1947 and then in 1950 the so-called ‘council system’ was introduced, thus ending the office. In his speech in 1954, Lajos Ács, a member of the ruling communist party’s political committee, said frankly: ‘The Soviet Army chased out the főispáns, the főszolgabírós, the repressive clerks, gendarmes, military officers, landlords, owners of large factories, banks and commercial companies.’[12] The centuries-old Hungarian office was thus shattered by the two dictatorships of the last century (Nazi and Communist).

[1] László Bernát Veszprémy, ’Gyilkos irodák. A magyar közigazgatás, a német megszállás és a holokauszt’, Budapest, Jaffa, 2019. 97.

[2] György Ránki (ed), ’A Wilhelmstrasse és Magyarország; német diplomáciai iratok Magyarországról, 1933-1944.’ (Budapest: Kossuth, 1968), 837.

[3] Ránki (ed), ’A Wilhelmstrasse és Magyarország’, 845.

[4] Yad Vashem Archives, T.16/47. 73.

[5] Anders E. B. Blomqist, ’Local Motives for Deporting Jews. Economic Nationalizing in Szatmárnémeti in 1944’, Hungarian Historical Review, 2015/3. 673–704, here 683.

[6] László Csősz, ’Konfliktusok és kölcsönhatások: zsidók Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok megye történelmében’, Szolnok: MNL Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok Megyei Levéltára, 2014, 196.

[7] For Mérey’s testimony and the subsequent statements, see: BFL, XXV.1.a.1945.1605. 12, 16, 20, 28, 30, 84-85, 104.

[8] Vác Város Levéltára (hereinafter VVL), 93-a. 21/1944.

[9] VVL, 93-a. 146/1944. and 51/1944.

[10] VVL, 93-a. 160/1944.

[11] Fehérvári Hírek, 6 November 1947. 1.

[12] Szabad Nép, 8 November 1954. 1.