1848 was a troubled year for most of Europe – the Springtime of the Peoples brought about many revolutions across the continent. Hungary was no exception – on 15 March 1848, inspired by the events in Vienna, the youth of Budapest revolted against the Habsburg establishment which ruled Hungary at the time. The 1848–1849 Revolution and Freedom Fight that started on that day fundamentally changed the course of Hungarian history, and it remains the core of Hungarian national identity to this day.

One of the most popular myths about the Revolution is the imaginary scene of the young poet, Sándor Petőfi reciting what became the Revolution’s signature lyrics, the ‘National Poem – Rise up, Hungarian!’ on the stairs of the Hungarian National Museum. Albeit no historic sources prove the accuracy of this myth, there is a memorial plaque remembering the moment at the Museum’s stairs; and it is also a popular destination for school children to place wreaths, flowers and flags to commemorate the Revolution.

For a while, the struggle for Hungary’s independence seemed to be leading to success – in April 1849, the Glorious Spring Campaign brought many victories to the Hungarian army

While initially the revolutionaries demanded only the end of censorship, the establishment of an independent parliament, the creation of a responsible national government, and release of political prisoners, the demands soon turned into a cry for independence. The attempt to democratise Hungary soon provoked a military conflict between Hungary and the Imperial-Royal Army. For a while, the struggle for Hungary’s independence seemed to be leading to success – in April 1849, the Glorious Spring Campaign brought many victories to the Hungarian army under the leadership of the talented commander-in-chief, General Artúr Görgey. As the Habsburg Empire was on the brink of being humiliated by the Hungarian revolutionary army, the Austrian emperor asked his Russian counterpart, Czar Nicholas I, to send troops to defeat the Hungarian Freedom Fight. The joint forces of Austria and Russia eventually succeeded in crushing the Hungarian revolutionary effort. On 13 August 1849, General Artúr Görgey surrendered to the Russian Army – but not to the Austrians.

Although in the immediate aftermath of the revolution Hungary was severely oppressed, the Habsburgs did not dare to abolish all the achievements of the struggle – some even argue that the Compromise of 1867, which turned the Habsburg Empire into the dualist Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, granting Hungary more autonomy, would not have been possible without the Revolution. The Revolution united the nation and revealed its strength – Austria on its own had been unable to overwhelm the Hungarians’ determination to fight for their national freedom. The Revolution and Freedom Fight was, therefore, a crucial part of nation-building, and it also led to the modernisation of the country.

15 March, and the public memory of the Revolution, have the power to mobilise Hungarians to this very day – which is why it was feared both by the Habsburgs and the communists. The first unofficial celebration of 1848 took place in 1860. The commemoration was not welcomed by the Habsburg establishment – one of the young attendees of the event was shot dead by the police. Later, in 1945, the interpretation of the Revolution got a communist spin – the communist world revolution was depicted as the continuation of 1848 and communist politicians attempted to win legitimacy by comparing themselves to Hungary’s leaders during the Revolution and Freedom Fight. The fact that the Freedom Fight was defeated with Russian help was a bit of an inconvenience, but it could be easily blamed on Russian Imperialism, which was corrected by the new rulers of Soviet Russia.[1]

By the 100th anniversary of the Revolution in 1948, the communists had completely reshaped public remembrance of 1848 to suit their goals – they presented Mátyás Rákosi, the then dictator of Hungary, as the “new Lajos Kossuth” (the number one Hungarian statesman of the Revolution). As tensions between Yugoslavia and the Soviet bloc intensified, Tito was depicted as Jelacic, the Croatian Ban who first used military force against Hungary on behest of the Habsburgs, which turned the ‘lawful revolution’ of 1848 into a Freedom Fight. The nationalist element in the Freedom Fight and Revolution, however, continued to represent an ideological threat to the Communist rule. To play down the significance of the day, in 15 March was abolished as a public holiday in 1950.

In 1956 one of the demands of the Revolutionaries was to reinstate 15 March as a national holiday

The communists’ fear of 15 March was not unfounded – in 1956 one of the demands of the Revolutionaries was to reinstate 15 March as a national holiday. In 1956, the demand to change the country’s coat of arms, which included communist symbolism, to the so-called Kossuth coat of arms, also appealed to the memory of 1848-49. After the 1956 Revolution was defeated by the Soviets, the revolutionary rhetoric did not disappear from the streets of Budapest, but it started to traced back its legacy to 1848 even more. The ‘in March we start over’ slogan became the call for a new Revolution against communist oppression. Although March 1957 did not bring another revolution to Hungary, the memory of 1848-49 was always a source of inspiration for Hungarians to stand up for their freedom and independence. Not surprisingly, 15 March was still an anniversary communists feared even as late as in 1986, just a couple of years before the collapse of the regime, so when protestors gathered in front of Sándor Petőfi’s statue that day, they were beaten up and chased away by the police.[2]

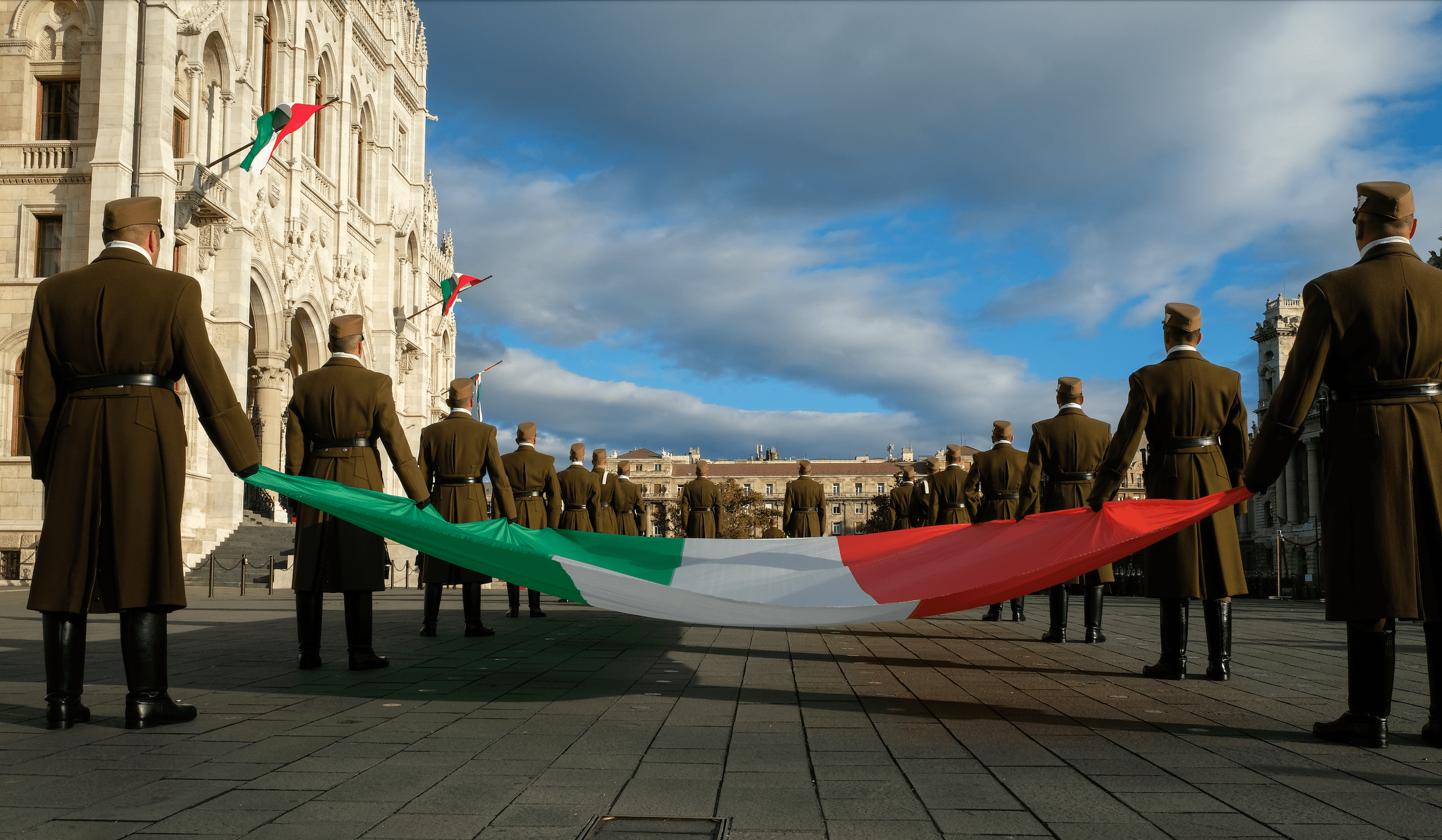

After 1989, 15 March finally regained its prestigious place as a major national celebration in Hungary which is now commemorated across the board. Of the three national holidays Hungary celebrates (23 October – 1956 Revolution, 20 August – State Foundation Day of Hungary, 15 March – 1848 Revolution) 15 March is the most popular one. The heroes who defined the politics and the literary life of the day are also among the most renowned people of Hungary. In each and every Hungarian village, there is a public space named after István Széchenyi, the Greatest Hungarian, Ferenc Deák, the Sage of the Country, Lajos Kossuth or revolutionary poet Sándor Petőfi. In Budapest only there are well over a hundred public places named after people who had an important part to play in the Revolution.

[1] Péter Bihari, ‘The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and its consequences,’ in Crossroads of European Histories – Multiple Outlooks on Five Key Moments in the History of Europe, Strasbourg, Council of Europe Publishing, 2009, p. 50.

[2] Péter Cseresnyés, ‘March 15: How the Communists Attempted to Exploit It, Then Feared It,’ Hungarytoday.hu, 2020, https://hungarytoday.hu/march-15th-how-the-communists-attempted-to-exploit-it-then-feared-it/, accessed 13 March 2022.