Although it is somewhat known in the Hungarian Jewish community, it is a surprising fact that the anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic undercover investigation and the related criminal proceedings that took place in the late sixties, under the codename ‘Shalom’, have not yet been written up by any historian.[1]

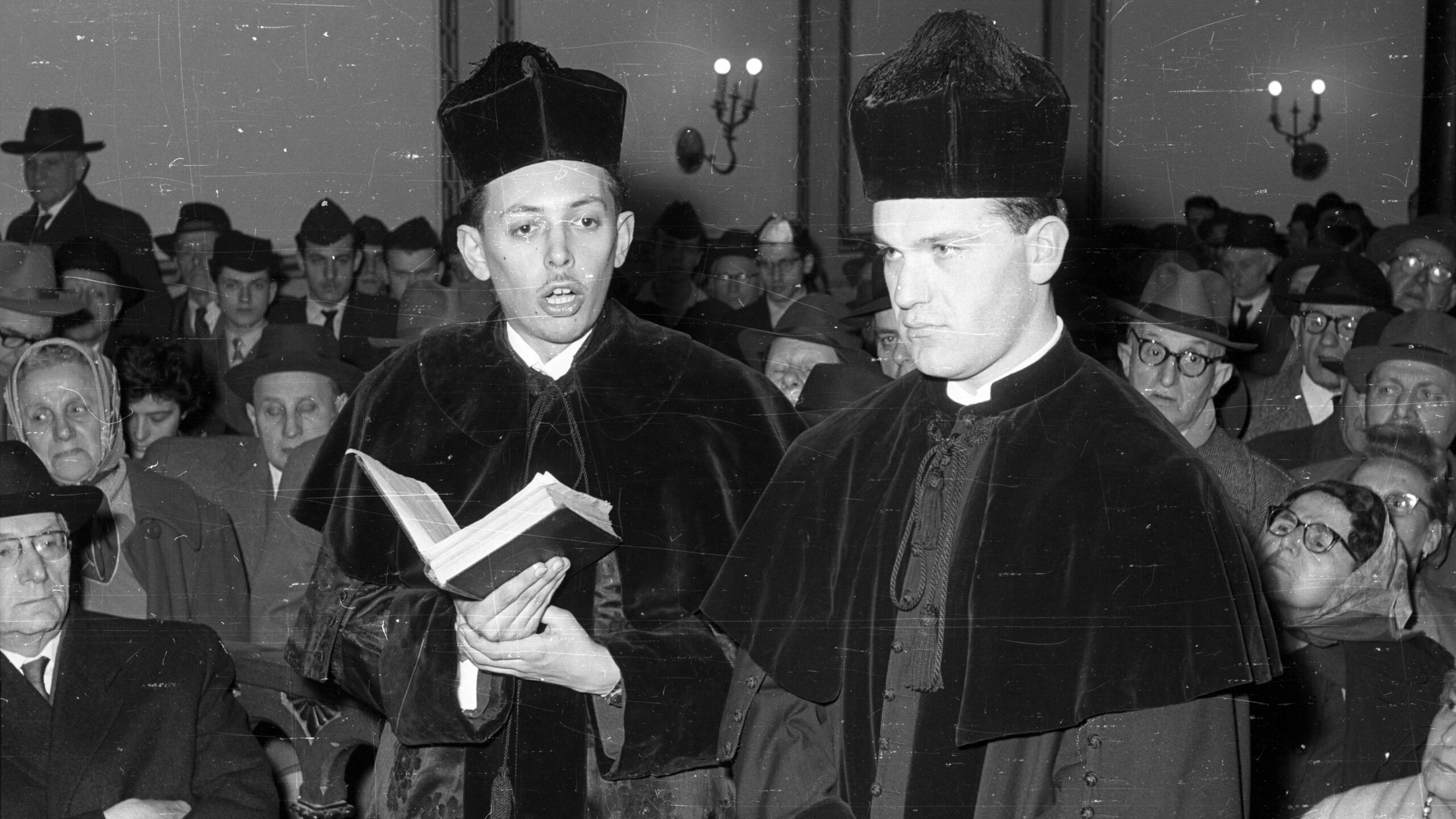

The story’s central figures was the famous rabbi, Tamás Raj (1940–2010), the former chief rabbi of Szeged in Southern Hungary, who was targeted by the Communist Kádár regime for supposedly organizing Zionist groups in the 1960s. This investigation was codenamed ‘Shalom’.

Although Hungary maintained diplomatic relations with Israel until 1967, from the early sixties onwards the Ministry of the Interior (Belügyminisztérium, BM) began to keep a special watch on the perceived or real members of the Hungarian Zionist movement.[2] Although such groups had been targeted before, some did not ‘understand the warning’.

The ‘Shalom’ group file was opened in November ’66, after thirteen Hungarian-Jewish youths had made aliyah through Yugoslavia during the year. The targets of the new investigation were Gábor Halmos, a mechanic and member of the Jewish community of Zugló (Budapest’s 13th district); Iván Beer, a rabbinical seminary student; a student identified as J. C.; István Donáth, a community leader; József Donáth, a student; György Mandler, a student at the University of Szeged; Ferenc Raj, a rabbinical seminary student; Alfréd Schőner (who later became a renowned rabbi); and the rabbis Artúr Geyer and Tamás Raj. Geyer was then rabbi of the Frankel Leó Street synagogue, while Tamás Raj was Chief Rabbi of Szeged, inaugurated by the famous rabbi Sándor Scheiber in 1964. The contact between the Szeged and Budapest groups was maintained by Tamás Raj in letters to József Donáth.[3]

The group was reported to the police by several sources at the same time. The daughter of an as-yet-unknown agent codenamed ‘Kasszás’ told her father that Geyer was organizing a Jewish youth group, and the agent ran to his handler to report his daughter’s words.[4] Of Ferenc Raj’s youth group, his future colleague, the rabbi László Salgó (codenamed ‘Sárvári’) was a police informant.[5] At the same time, the head of the Magyar Izraeliták Országos Képviselete (National Representation of Hungarian Israelites, MIOK), Géza Seifert was reporting to the State Bureau of Church Affairs (ÁEH) under his own name. In this particular case, he wrote that the Raj-brothers and Geyer were organizing a Zionist group.

Some of the young people were already known to the Communist Secret Service. C.J., a Jewish secondary school student, recited a poem by the Zionist Hebrew poet Chaim Nachman Bialik at a community event in Székesfehérvár in the summer of ’64, instead of the poem she had agreed to recite—this was enough for the Secret Service to start collecting information about her.[6] The Secret Service kept a very close watch on the youth, collecting descriptions of character of young Jewish men and women (even secondary school students) and information about their foreign contacts.[7] Ferenc Raj was also in trouble as a result of a conflict with MIOK. In the spring of ’66, he praised Hannah Szenes in a synagogue speech, and so Seifert banned him from making speeches.[8]

‘The Secret Service kept a very close watch on the youth, collecting descriptions of character of young Jewish men and women’

Ferenc’s brother, Tamás received a warning from the ÁEH in the summer of ’66, but he ignored it and continued to organize Jewish groups. As a result, the Secret Service started an undercover investigation against him. In this investigation they were largely assisted by the agent codenamed ‘Szegedi’ (later: ‘Pickering’), who in reality was a Jewish cantor, Imre Rubovits. Rubovits was recommended by ‘Sárvári’ to the Secret Service, as a close friend of Raj, but in reality, he had no love for his rabbi and therefore accepted the position of a spy immediately. Rubovits was an enthusiastic and active secret service agent, who reported on a number of Jewish community figures. Later he was sent to Sweden and Western Germany, and he reported from there as well. ‘Szegedi’ only made one mistake—or rather, his handlers made the mistake, effectively exposing him. After he reported that Raj prayed in Hebrew for the State of Israel, the policemen questioned Raj about this. ‘Raj returned to Szeged and attacked me, because, according to him, it was I who had spoken to the police. He based his accusation on the fact that we are the only two people in Szeged who speak Hebrew.’[9]

Raj was watched not only by this agent, but local policemen also followed him on the street in civilian clothes. They gave Raj the codename ‘Tom’ and recorded everything he did during the summer of ’67, including going to the post office or stopping on the street to talk to friends.[10]

The case was further complicated by the fact that in September ’66 an investigation had been launched against two young Orthodox Jewish men, József Sárvári and Miklós Böhm. The police accused them of having volunteered to be foreign agents. One report claimed that in July ’66 they tried to make contact with the American embassy, and regularly visited the Israeli embassy. The two accused said that they were members of a Zionist group in the Frankel Leó street synagogue.[11]

All in all, the Communist Secret Service could see the outlines of a juicy anti-Zionist case, involving previously known or unknown Zionists, connections to the Israeli embassy, and possible connections to the Americans or the Yugoslavians. In this context, it is not surprising that they took relatively serious steps: they proposed house searches, the obtaining of incriminating evidence and a future criminal prosecution.

‘Szegedi’ was also originally supposed to have been involved in breaking into Rabbi Raj’s home at night with the police in March 67, when Raj was not at home, and translate any Hebrew materials that could be found. (It seems that ultimately ‘Szegedi’ was not present during the house search, the police just gave him the materials they had found.) It turned out that ‘dangerous Zionist literature’ in Hungarian was found in the rabbi’s flat—for example, Herzl’s Jewish State— and Free Masonic material as well, from the papers of the former Szeged congregation president Róbert Pap.[12]

Raj and his associates were finally interrogated in September and were explicitly questioned about their relations with the Israeli embassy. The plan of action was prepared by the Secret Service, but the operation was carried out jointly with the regular police. Tamás Raj defended himself during the interrogation by claiming that he was not a Zionist and had not formed an association: this was technically true, as Raj was not a member of any movement on paper and had not registered any association.

The ‘Shalom’ case ended with the court of first instance sentencing József Donáth and Gábor Halmos to four months of suspended imprisonment each on 14 March 1968. They also sentenced the people who had made aliyah in absentia. The sentences were upheld in appeal on 9 October 1968 and became binding. In addition, Iván Beer, István Donáth, Artúr Geyer, György Mandler, Ferenc Raj and Tamás Raj were issues a police warning. Schőner, although found to be a member of the group, was not charged with any offence.[13]

In 1970 Seifert fired Raj from the rabbinical seat in Szeged: the official reason was that during a theatrical performance he allowed the actors to perform bareheaded. In reality, as one local agent codenamed ‘Piéta’ reported, Seifert had acted on the orders of the Secret Service, which would not be surprising, considering that the MIOK president himself was an informant. The information on the background of Raj’s firing had apparently come from Ármin Varró, the president of the Szeged congregation, who had heard it from Seifert himself.[14] They wanted to move Raj to the Nagykanizsa congregation, but he did not accept that post, as it would have legitimized Seifert’s decision, and the congregation in Nagykanizsa was very small. According to the family’s recollection, he was subsequently banned from rabbinic activity, a ban that lasted for 15 years.

[1] See for example here https://mazsihisz.hu/kozossegeink/nagy-elodeink/nagy-elodeink-dr-raj-tamas-forabbi-1940-2010 or https://www.szombat.org/archivum/pres-alatt-illegalis-mukodese-allando-veszelyforras-a-kozbiztonsagra-1352774047

[2] See András Kovács, A Kádár-rendszer és a zsidók,Bp., Corvina, 2019. 301–422. See also the writings of Attila Novák: https://www.szombat.org/tortenelem/cionizmus-es-cionistak-a-kommunista-allambiztonsag-szemeben-magyarorszagon-1 and https://www.szombat.org/tortenelem/cionizmus-es-cionistak-a-kommunista-allambiztonsag-szemeben-magyarorszagon-ii

[3] Állambiztonsági Szolgálatok Történeti Levéltára (Archives of the State Security Services, hereon cited as ÁBSZTL), 3.1.5. O-13772/1. 19.

[4] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-13772/1. 194.

[5] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-13772/1. 193.

[6] ÁBSZTL O-17169/1. 207.

[7] ÁBSZTL 3.1.5. O-17169/1. 215.

[8] ÁBSZTL 3.1.5. O-13772/1. 43.

[9] ÁBSZTL 3.2.3. Mt-1208/2. 125.

[10] ÁBSZTL 3.1.5. O-13772 /2. 128.

[11] ÁBSZTL 3.1.5. O-13772/1. 136.

[12] ÁBSZTL 3.1.5. O-13772 /2. 121, 201-202, 217.

[13] ÁBSZTL 3.1.5. O-13772/3. 535-539. and ÁBTL 2.2.1. III/4.8./1563. See also: ÁBSZTL 3.1.9. V-155325/1. and ÁBSZTL 3.1.9. V-155325/2.

[14] Ferenc Katona, ‘Fedetlen fővel a zsinagógában. Az 1970-es szegedi Mózes-előadás történetéhez,’ Szombat, 2012/9. 13-17. and ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-15929. 106.