After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Budapest—until the unification in 1873 still Buda, Pest, and Óbuda—underwent rapid development and became one of the defining metropolises of Europe by the turn of the century. As part of that process, not only the development of today’s historic parts of town took place, but, among other things, huge investments also began in the area of Lágymányos Lake between today’s Liberty Bridge and Rákóczi Bridge.

During the Danube Regulation works in the 1870s, a dam was built at Lágymányos Bay, thus creating the Lágymányos Lake. Hungarian circus and theatre director Károly Somossy, the owner of one of the legendary centres of Budapest nightlife, the former Somossy Orfeum, and the most decisive figure in the Hungarian entertainment industry of the era, came up with a grandiose idea for the use of the area: taking advantage of the hype around the 1896 Millennium Exhibition and celebrations, he set out to build a luxurious party district modelled on the dominant cultural centre of the era, Constantinople.

Hungarian writer and journalist Gyula Krúdy opined that it was Somossy who

‘taught Budapest how to party’.

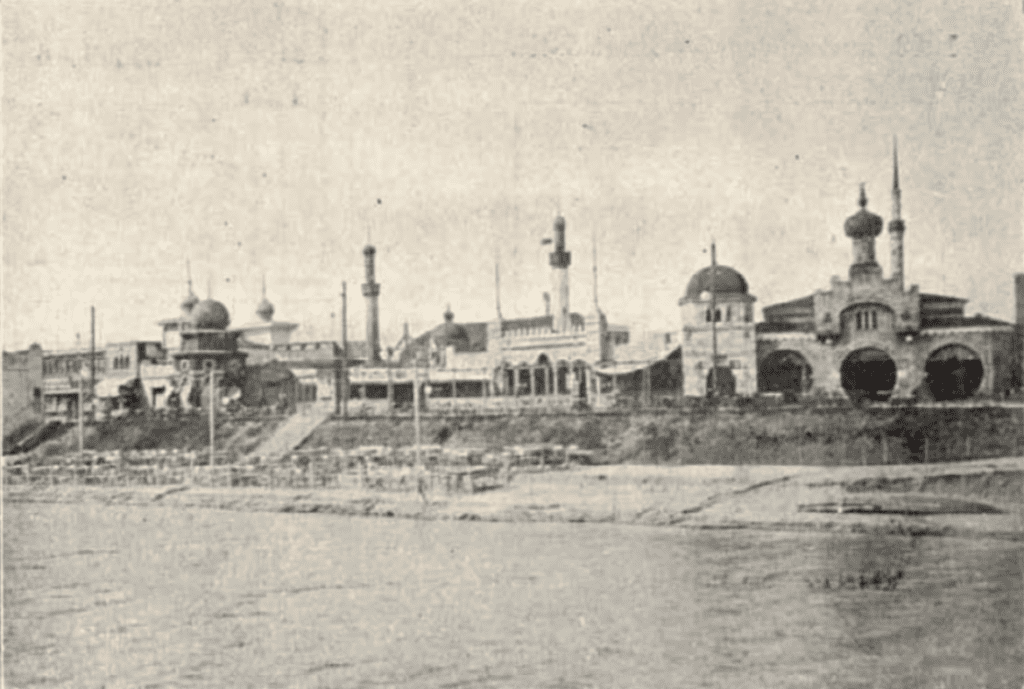

In the spring of 1896, around Lágymányos Lake and on the small island located in the middle of it—which today would encompass the territory of the University of Technology and Economics—, the ‘party district’ named Constantinople in Budapest was built by means of loans, which was described in the 6 September 1896 issue of the weekly Vasárnapi Ujság as follows:

‘The part of Constantinople in Budapest that has been completed so far already has many attractions. First of all, let us mention the beautiful lake formed by one of the Danube branches closed during the Danube Regulation, which stretches between Gellért Hill and the connecting bridge and is 540 meters wide in some places. There is also an island with willows and groves in the middle of the lake. This lake and the island on it actually provided the basic idea for the establishment of a Little Constantinople in Budapest. The lake, which has already been named after the Bosporus, is crossed by a ten-metre-wide wooden bridge resting on strong pillars. The bridge is complemented by about 30 electric arc lamps placed on wooden structures towering from the pillars, which cast a blinding glare into the dusk and viewed from the bridgehead, together with the light of the also lavishly illuminated site, offer a delightful sight.’

Similar to the Millennium Exhibition, the buildings of the party district were made of lightweight plaster and wood structures, thanks to which the entire construction took only two and a half months. All the buildings evoked an atmosphere of Constantinople; there were oracles under the arches of the bazaar rows of narrow streets, and all kinds of oriental goods were available as well, exported to Budapest by Istanbul’s most famous merchants. Replicas of the Hagia Sophia and the Galata Bridge were also erected, as well as mosques and minarets. Camels were everywhere as far as the eye could reach, and on the lake, people could row in Turkish rowboats brought from Constantinople. Besides, there were a Fracati’s French theatre, several coffee houses—of which the Szultána Coffeehouse was the most popular one—, workshops for Italian glassblowers, and two ‘harems’ with Turkish girls as well, which, however, did not function as real brothels, as Little Constantinople was opened mainly for families.

The daily Pesti Hírlap said the following about the harems on 24 May 1896:

‘We must point out that the management has placed the greatest importance on showing the Turkish life faithfully, in its original authenticity, with certain Mohammedan morals and customs. This is also to say that there are no ‘fake harems’ or any such places on the site, so it is perfectly appropriate for every family man to take the female members of his family there, just as there were many women of honourable families at today’s showcase, too.’

Furthermore, various performances were held on the lake on battleships built for the events, which were often even sunk to entertain the guests. In the middle of the lake, there was a castle-like fortress standing on a small island, from which fireworks were often shot off. The entrance fee was 30 kreuzers (a small coin of the Habsburg Monarchy at the time) on regular days and 40 kreuzers on fireworks days.

Since the central part of Budapest was far from Little Constantinople, special omnibus and shipping services transported those who wanted to have fun to the party district, where up to 40,000 people could enjoy themselves at one time.

The downfall of the grandiose building complex was ultimately caused by the location of the party district: since the summer of 1896 was very rainy, due to the swampy area the entertainment centre was built on and the inland lake created with the construction of the dam, mosquitoes infested the whole area during the summer months so much so that it became unbearable for visitors to stay there. Thus, the income fell so much in just half a year that by the fall of 1896 bankruptcy became inevitable and Little Constantinople’s short life came to an end.

Click here to read the original article