The following is an adapted version of an article written by Barnabás Leimeiszter, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

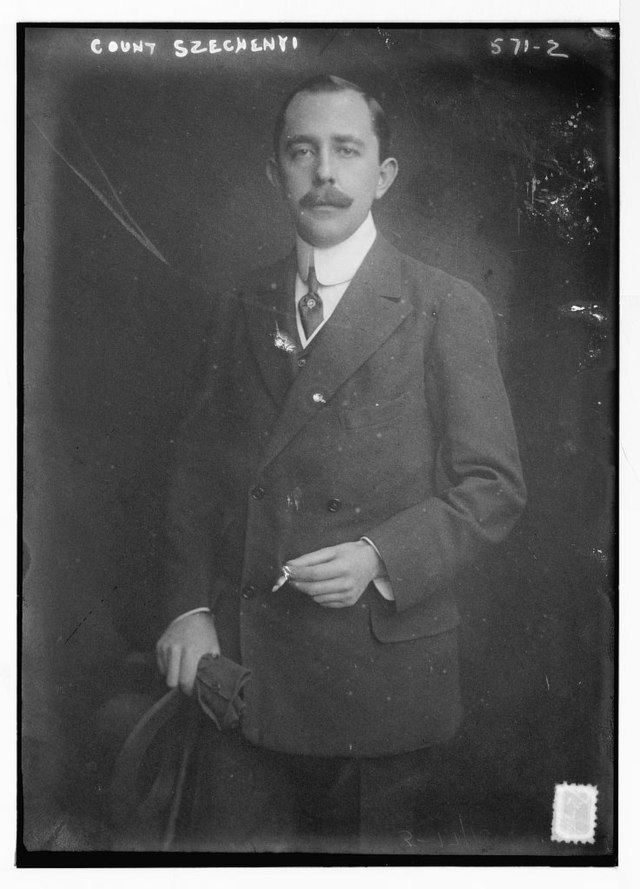

One of the most high-profile weddings of the turn of the century was the New York wedding of István Széchenyi’s distant relative László Széchenyi and Gladys Vanderbilt. Ady saw the Count as a golden boy detached from Hungarian reality, but he later proved his patriotism as Hungarian ambassador to Washington and London.

László Széchenyi was the grandson of István Széchenyi’s brother, Lajos Széchenyi, and his father, Imre Széchenyi, an influential diplomat who grew up at the Viennese court, became friends with Otto von Bismarck early in his career and served as ambassador to Berlin for a long time. (More recently, his work as a composer has led to the rediscovery of Imre Széchenyi, also known as the ‘Waltz King’, who was friends with the younger Johann Strauss and Ferenc Liszt, who composed the transcription of his Introduction and Hungarian March. In addition to being a diplomat, he was also a brilliant pianist, and his playing even dazzled Queen Elizabeth.) It was during his overseas travels that László Széchenyi, who was also preparing to become a diplomat, met Gladys, the wealthy daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt—a railroad and shipping magnate who died in 1899—whom he married in 1908. The attention and controversy the marriage attracted are illustrated by the fact that—as the Széchenyi necrology pointed out in the political daily Ujság—a senator demanded before the US Congress that ‘export duties be imposed on rich American brides who take their millions to Europe’.

Reacting to attacks from American politicians and the press, Széchenyi launched an angry outburst against not only his critics but the American lifestyle in general, which was causing wealthy young American girls to seek European grooms:

‘What kind of home can you Americans provide…who swallow your wife’s love with hurried and nervous rapidity as you eat your lunch, and then hurry off and leave your wife alone. Hence, rich girls, who cannot come to terms with your way of life, prefer to marry strange men rather than you.’

‘“He has lived abroad, lives abroad, and wants to live abroad, our problems, our Hungarian problems, do not bother him”’

However, it was not only in the United States that people spoke with condemnation or sarcasm about the intertwining of (often impoverished) old noble families and the moneyed aristocracy. Endre Ady, in his article ‘Rózsika and Gladys’ in the periodical Budapest Napló, poked fun at the love, which had become an ‘international commodity’, comparing Széchenyi’s wedding with the case of Rózsika Wertheimstein from Oradea who had married into the Rothschild family. (Magyar Krónika dealt with her briefly in their article on Emma Ritoók’s memoirs: born into a noble Jewish family, Rózsika was one of the leading lights of the Hungarian irredentist cause in England after Trianon.) In another article, Ady mocked and criticized László Széchenyi:

‘Here is how the glory of the great István Széchenyi must rise. By the writings of paid American reporters and the good fortune of a gentleman named Széchenyi marrying a Vanderbilt girl. A Széchenyi, by the way, whom it would perhaps be an exaggeration to call even the smallest Hungarian. He has lived abroad, lives abroad, and wants to live abroad, our problems, our Hungarian problems, do not bother him.’

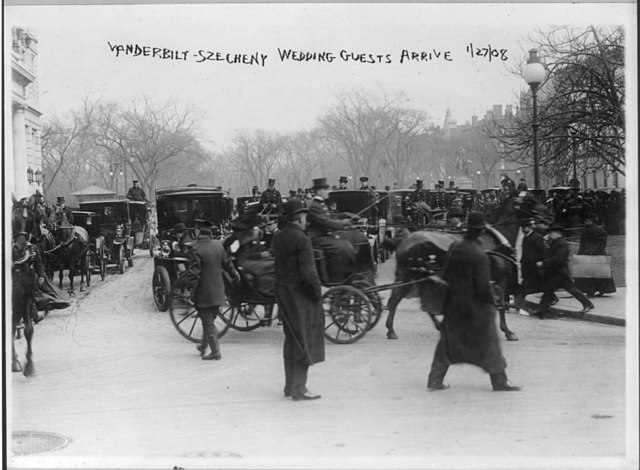

But let’s see how the New York wedding went. On Fifth Avenue, a huge crowd waited to see the bride and groom and their guests. There were so many that police had to be called out.

However, the newlyweds themselves used a back entrance to evade the curious crowd skilfully. The curious onlookers ‘could only see fur-clad figures hurrying out of carriages and cars, disappearing in a second into the bright stairwell of the Vanderbilt Palace,’ the daily Pesti Napló reported. The wedding, which lasted barely ten minutes and was attended by the crème de la crème from New York and abroad, was calm and dignified, with the bride choosing the music (Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony, excerpts from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, and the triumphant march of Goldmark’s The Queen of Sheba). The Pope also sent his blessing in a ‘cable telegram’, expressing his hope that the Count and his wife would visit him in the Vatican as soon as possible. The only inconvenience was the appearance of a team of financial officers at the Vanderbilt Palace, having received an anonymous (and, as it turned out, unfounded) report that the family had not paid customs duty on the dowry from Paris.

‘After the ceremony, they fled in hiding to one of the farms of Cornél Vanderbilt, only to return home after two weeks, first crossing the sea, then through England, France, and Upper Italy. The little Slavic village of Őrmező, in Zemplén County, was the first place where they appeared in public,’ the Vasárnapi Ujság reported, giving further details: ‘The reception of the Count and Countess was very kind and fancy. The village was beautifully decorated from the station to the castle. The streets were crowded with the festively dressed people of the village and the neighbourhood, lined on both sides of the roadway. The women and children waited for the celebrated couple on tribunes erected on the right and left, and they were received at the station by a banderium of a hundred peasants and the intelligentsia of the area…Countess Gladys Vanderbilt…wants to be worthy of the great name she bears and, above all, wants to learn our language. In this respect, she is already making good progress since she pronounces the little she has managed to learn in the short time she has had, without any mistakes.’

‘“If Count Széchenyi had done nothing for his country but win the heart of Gladys for the Hungarian cause, he would have done enough”’

After the couple arrived in Hungary, they bought a villa on Andrássy Avenue, and the building was considerably enlarged, colloquially referred to as the Vanderbilt Palace (today it houses the Embassy of the Russian Federation in Hungary). A few years later, Széchenyi made the papers by setting up companies with the Vanderbilt family to sell abroad a Hungarian-developed wireless information transmission method: more specifically, a telegraph system that facilitated communication between submarines and the steering of torpedoes. The Count was in America when the First World War broke out, and on his return, he enlisted in the army and fought through the war. Gladys made the Andrássy Avenue Palace available to the army, and after the war, it was at her initiative that US President Herbert Hoover decided to launch a humanitarian programme to help Hungarian children in need.

‘Even if Count László Széchenyi had done nothing for his country but win the heart of Gladys Vanderbilt for the Hungarian cause, he would have done enough because Gladys Vanderbilt achieved much, and the fruits of her achievements were enjoyed by Hungarian families in need’, the weekly Amerikai Magyar Népszava concluded.

Széchenyi served as a captain and later took on an important diplomatic role: he was appointed Hungary’s first ambassador to Washington, a post he held for eleven years. ‘László Széchenyi had a difficult task in Washington. Among the difficult tasks was, to mention just one, the liberation of Hungarian assets confiscated in America during the Great War,’ as the article quoted above says. Through his wife’s network of contacts alone, Széchenyi was able to make an effective contribution to improving Hungarian–American relations and the situation of Hungarians in the New World. When he left his post in 1933 newspapers wrote that his departure was ‘considered a great loss by the American political and diplomatic establishment in Washington,’ adding that ‘Count Széchenyi and his wife, known to have been a member of the most distinguished American society by birth, were extremely popular in Washington circles.’ It is interesting to note that in 1924 a rumour was circulated (certainly without any foundation) that Hungarian Americans were plotting to elevate the Count to the Hungarian throne because, in that case, ‘the wealth of American billionaires could find a home in Hungary and prosper the country’. As reported, this plan was unveiled to Horthy by the Ébredő Magyarok Egyesülete (Association of Awakening Hungarians).

In 1927 Count Széchenyi was on his summer holiday in Hungary when he suffered a serious accident: on his way to Svábhegy, on the Istenhegyi Road—he was carrying Countess Wenckheim home—their car collided with a pillar of a stone bridge, and a piece of broken glass injured the Count’s left eye. Széchenyi was quickly taken to hospital, but the next day, it became clear that the eye could not be saved. Professor Emil Grósz ‘immediately proceeded with the operation and removed the damaged eyeball in a ten-minute operation,’ as Ujság reported. According to the daily, Széchenyi bore this loss ‘manly and calmly’. Governor Miklós Horthy and Deputy Prime Minister József Vass personally inquired about his condition, and he was also visited in the hospital by the British Ambassador in Budapest, the Prime Minister’s representative, István Bárczy, the State Secretary, and several members of the aristocracy. Three years later, the newspaper Esti Kurir reported that Count Széchenyi sued Béla Grünwald, the owner of the vehicle whose headlights blinded the driver of the car carrying the Count, for 50,000 pence.

After his service in Washington, Széchenyi was posted as ambassador to London, where he asked for his retirement because of his worsening heart condition. He died in 1938 in the Svábhegy sanatorium. Even after her husband’s death, Gladys Vanderbilt continued to be committed to helping the suffering Hungarians in need and died in 1965.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.