‘I am in contact with a certain higher power, or willpower, perhaps a power that can create worlds. It is the positivity that we call fate, the invisible master, or God; one we also believe to be the power of nature, which is all the same’, a quote by Csontváry.

There once was a small-town pharmacist in Hungary, a certain Mr Tivadar Kosztka, who was born in the region of Szepesség (Spiš), once a part of northern Hungary, but located in Slovakia today. He was also someone who, while attending to the duties of his honest profession, started to hear voices one day. ‘You will be the greatest painter of solar roads’—the voice said. So,

Mr Kosztka left behind the life he had known thus far to become a painter, and dedicated his remaining days to seeking artistic truth.

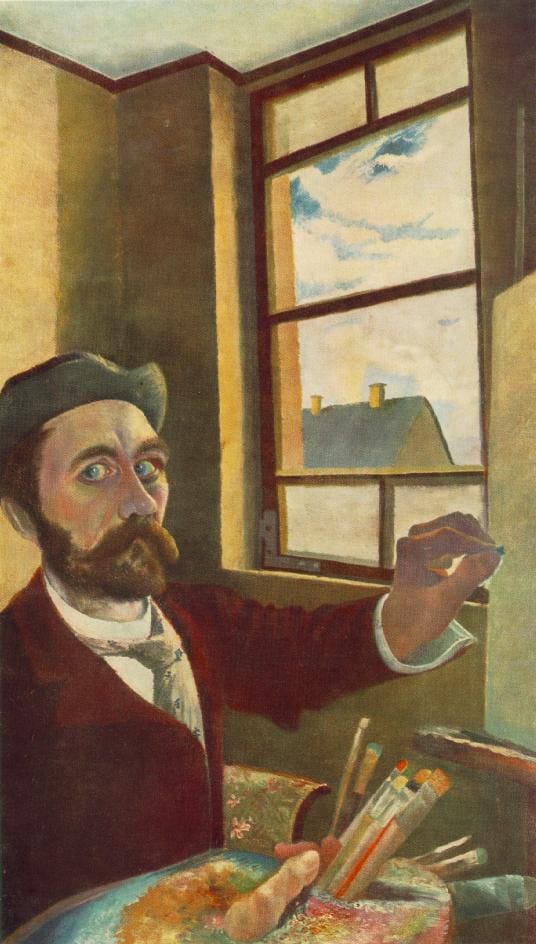

This is not a unique fate for an artist—it is quite typical, one might even say. However, Tivadar Kosztka went on a completely unique path thereafter. His artistry cannot be compared to anyone else, or any artistic trend. Taking on the pseudonym ‘Csontáry’, Tivadar Kosztka grew into a strange giant of Hungarian art—whose work is now being displayed at the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts, as part of a grand exhibition.

Tivadar Kosztka was born in the Northern-Hungarian town of Kisszeben in 1853, the same year as Vincent Van Gogh. His father was a pharmacist and amateur scientist who liked to do experiments, an eccentric small-town folk. The young Tivadar quickly became a fan of nature. After and in lieu of school, he often roamed the area, collecting things that caught his interest. Eventually, he followed in his father’s footsteps and travelled to Budapest where he got his pharmacist licence in 1875, then started practicing his new profession.

The years kept on passing by—then came 13 October 1880, when the pharmacist, while taking a break from his work, drew an ox-wagon on the back of a notepad. That’s when he heard the voice, calling on him to pursue the life of a painter.

Csontváry, embarking on an artistic career, did not just doodle around as a naive, untrained painter. Taking his ambitions seriously,

he travelled around Europe to train himself as a painter and improve his skills.

He first went to Rome where he studied the Renaissance pieces in the Vatican gallery; he then went on to travel to Paris, Munich, Karlsruhe, and Düsseldorf to study the craft of painting. On top of that, he also went on journeys to visit scenic, monumental, exotic landscapes that were so important to him. He explored Dalmatia, the Holy Land, Italy, and the Balkans as well.

His experiences in travel and his lonely visions inspired his greatest creations—the greatest, not just in the sense of artistic value, but also in literal size. Csontváry really liked painting his landscapes on gigantic canvases.

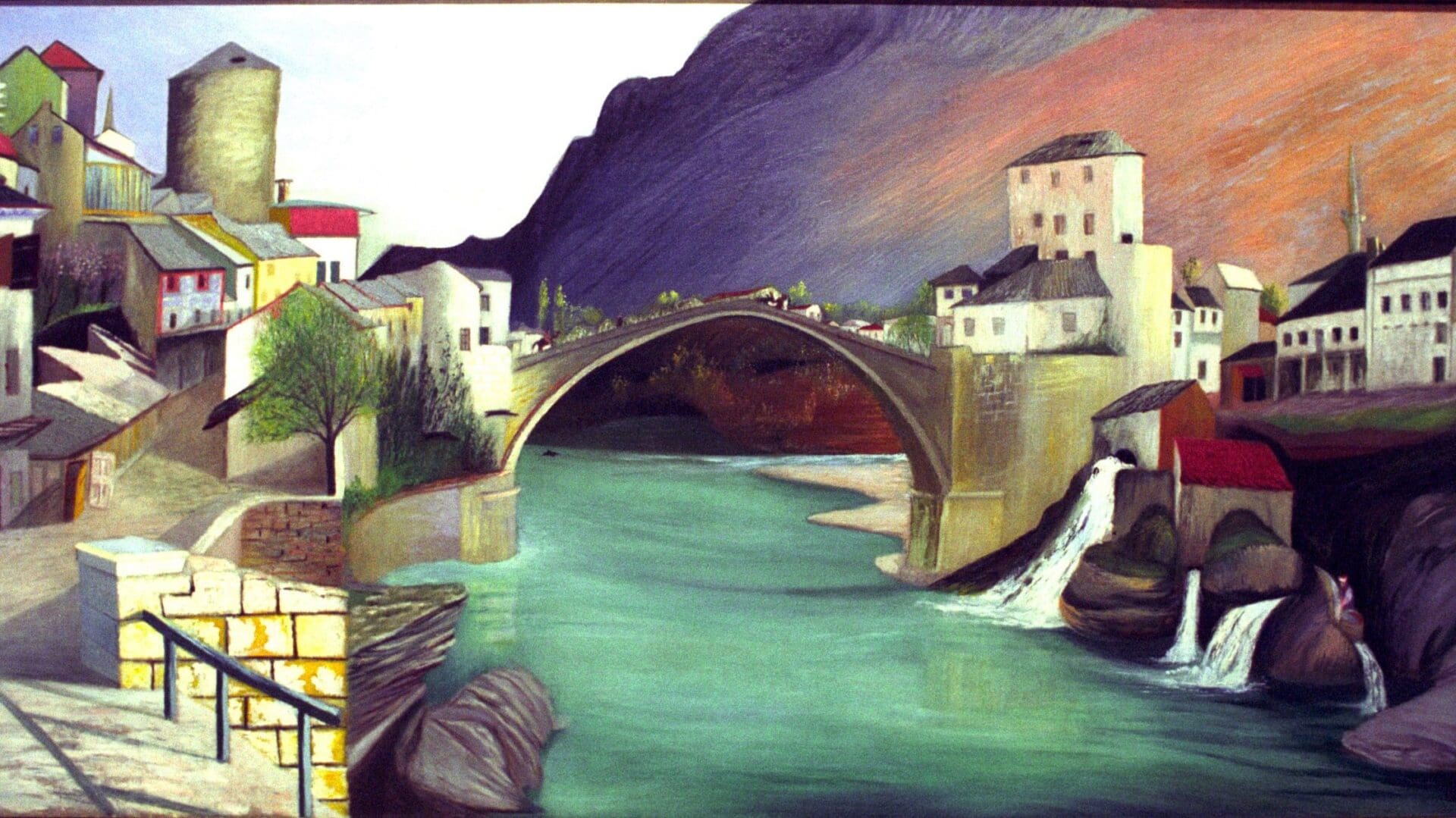

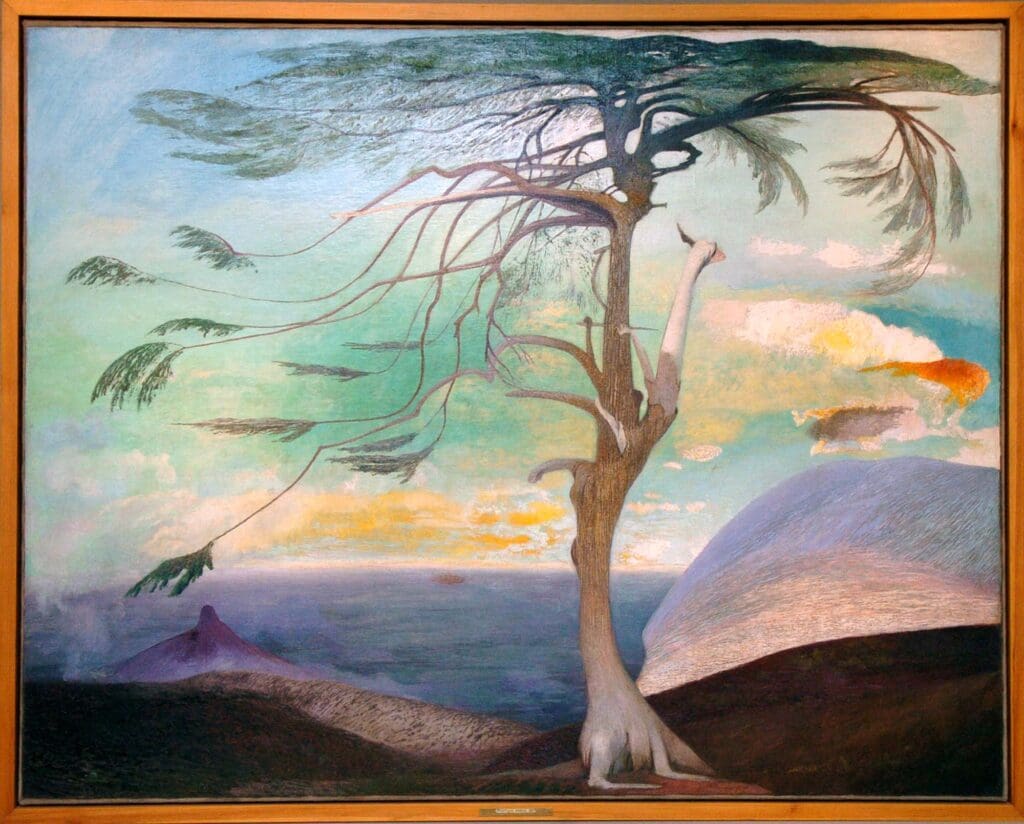

The Lonely Cedar of Lebanon, the Baalbek Temple, the Roman Bridge at Mostar, the Tatras, or the landscapes of Taormina, are all among Csontváry’s best-known, most astonishing works. In these pictures, the scenes elevate into dream-like visions, and extraterrestrial colours are shining through. We are leaving realism and stepping into the world of surrealism, or symbolism, as we lose ourselves in looking at these paintings. Most of Csontváry’s work seems timeless, or rather, existing beyond time—we barely find one or two allusions to the societal realities of the turn of the previous century.

‘He found the colours of the Solar Road: beaming yellow, flaming red, painful pink, and frightening blue. In the realm of Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka, sunshine is raving’, Gábor Szigethy writes in the foreword of Csontváry’s biography.

Csontváry, however, was not seeking his truth only in painting. He was also trying to create his own unique philosophy, which endured in his writings and pamphlets.

Belief in God, pantheism, and the scientific method are all present in them

—as if he was attempting to describe the theoretical background of his paintings, which give a visceral experience to the viewer.

His work as a painter cannot be separated from his scientific career as a pharmacist. What substance he used to create his paintings had been studied for a long time before it was found out that he did not just apply simple oil paint. Later studies have shown that he used a special mixture he concocted utilising his knowledge of chemistry. It included clay dust, aniline-based textile paint, salt, and water. Because of all this, his paintings could retain their original, grandiose colour scheme, which can still have a great impact on their viewers, laymen and experts alike.

Csontváry battled with his deteriorating health in his later years. Experts still debate whether or not he was schizophrenic. What is certain is that he lived out his days as a ‘lonely cedar’, a recluse among his fellow men. He was mainly eating fruit and vegetables, he did not smoke or drink alcohol. In addition, he never sold any of his works. He kept his creations, means of finding his own truth, to himself.

In the dusk of his life, he sold his pharmacy. In 1916, he was present at the coronation of the last King of Hungary, Charles IV, but he could never finish his planned painting of the event. Eventually, he passed away in the chaotic times following World War I, on 20 June 1919, in the days of the short-lived 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, in Budapest.

His exceptional body of work had quite an odd afterlife. His heirs did not know what to do with the pile of paintings amassed, so they tried to auction off its canvases to make some money. A young architect named Gedeon Gerlóczy accidentally stumbled into the studio where the artist’s relatives were packing up, when he noticed the unknown masterpieces.

‘While looking around, I accidentally kicked one of the cylinders, and the Lonely Cedar rolled out. The painting had such a great impact on me that I sunk deep into my thoughts, trying to come up with a way to save it’, Gerlóczy recalled later. The next day, the architect liquidated his inheritance to buy up the dozens of hidden gems of art. That is how Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka escaped being lost in the abyss.

‘I sacrificed my life in pursuit of knowing what is real, what the world has developed from and what it is developing into, since everything that is has developed from the will of positivity and everything that will be will develop based on the proclamation by positivity,’ Csontváry said of his own work.

The Budapest Museum of Fine Arts-National Gallery and the Janus Pannonius Museum of Pécs is celebrating the 170th anniversary of the birth of the great artist with a joint exhibition.

The art display will feature around 40 pieces,

as an homage to one of the most original and best-known figures in Hungarian art history.

László Baán, the Chief Director of the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts, had this to say:

‘I have been, we have been, thinking for a long time that it would be wonderful to put on a great showing of Csontváry in the Museum of Fine Arts, especially because our big spaces, our big ceiling heights are a great fit for it. Csontváry is just crying for such an exhibition hall.’

The exhibition will be taking place between 14 April and 16 June.