Hungarian Conservative has launched a ten-part series of articles on the past decade and a half of the Hungarian economy and society, titled ‘Revealing the Facts’. Rather than looking at a lot of different, isolated data it is worth providing an overview, comparing and analysing trends over time, in order to understand the details. In the first instalment of our series we looked at inflation. In parts two and three we highlighted that growing incomes and the security of livelihood, both of which have been experienced under the conservative governments since 2010, are of primary importance for Hungarians. The fourth analysis of the series explored the economic growth trends of the past decades. In part five important facts about the successful reduction of poverty in the country by conservative governments were revealed. Part 6 focused on how the current complex family support system evolved. This instalment provides a comprehensive overview of demographic trends in Hungary.

‘There is no finer investment for any country than putting milk into babies.’ (Winston Churchill)

‘Having children is like investing in a risky project. Postponing birth is like delaying an irreversible investment. It has an option value, which depends on its costs and benefits, and in particular on the additional risks motherhood brings.’ (David de la Croix & Aude Pommeret)

Let us start from afar! After the Second World War, with the Marshall Plan, Western Europe produced 135 per cent of what it had produced in 1938 by 1951, and countries moved towards the creation of the welfare state as the baby boom took place.

Meanwhile, in the countries of the Eastern Bloc, nationalization was at its height, with even the smallest workshops and shops being taken away from industrialists and merchants, and small plots of land from peasants. With the institution of social parasitism (‘közveszélyes munkakerülés’ in Hungarian) as a political crime, everyone was forced to work as an employee, so there was no prosperity in this region and the baby boom was not achieved as a result.

In Hungary, a strict ban on abortion between 1952 and 1955 and the simultaneous introduction of a childlessness tax led to a three-year increase in the birth rate. Then, on 4 June 1956 (the 36th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Trianon, which divided Hungary at the end of the First World War),

the first law in history legalizing abortion came into force and the birth rate fell sharply.

Mothers Can Stay at Home with Their Children Until They Are Three Years Old

In 1967, the first measure to support rather than penalise childbearing was introduced, allowing mothers to stay at home from birth to the age of three and to receive cash benefits during this period. All these positive measures have a fertility-enhancing effect for only a few years.

To counteract further deterioration in the early 1970s, and to create a market for the housing industry, a measure was introduced to provide substantial housing subsidies for promised children, just as those born between 1952 and 1955 (a large generation) were entering their most active childbearing years. This package of measures led to a huge increase in birth rates and fertility rates between 1974 and 1976. Later, as house prices rose, the subsidy became less helpful in buying a home and fertility began to fall. Therefore, from 1985, a higher pro-rata allowance was introduced for mothers up to the age of three of the child, instead of a grant.

Then came the regime change in 1990, when almost one and a half million jobs were unexpectedly lost, the average annual number of unemployed rose to well over half a million and fertility began to fall at an unprecedented rate. In all the countries of the former Eastern bloc, fertility declined until the turn of the millennium.

In our country the situation was exacerbated by the fact that not only were there no new discounts, but from 1988 the very cheap mortgage for buying a home was abolished. A decade of double-digit inflation pushed house prices so high that housing benefit was of little value, and in 1996 the mother’s working allowance and tax credits, including child benefit, which had been in place since the introduction of income tax in 1988, were abolished.

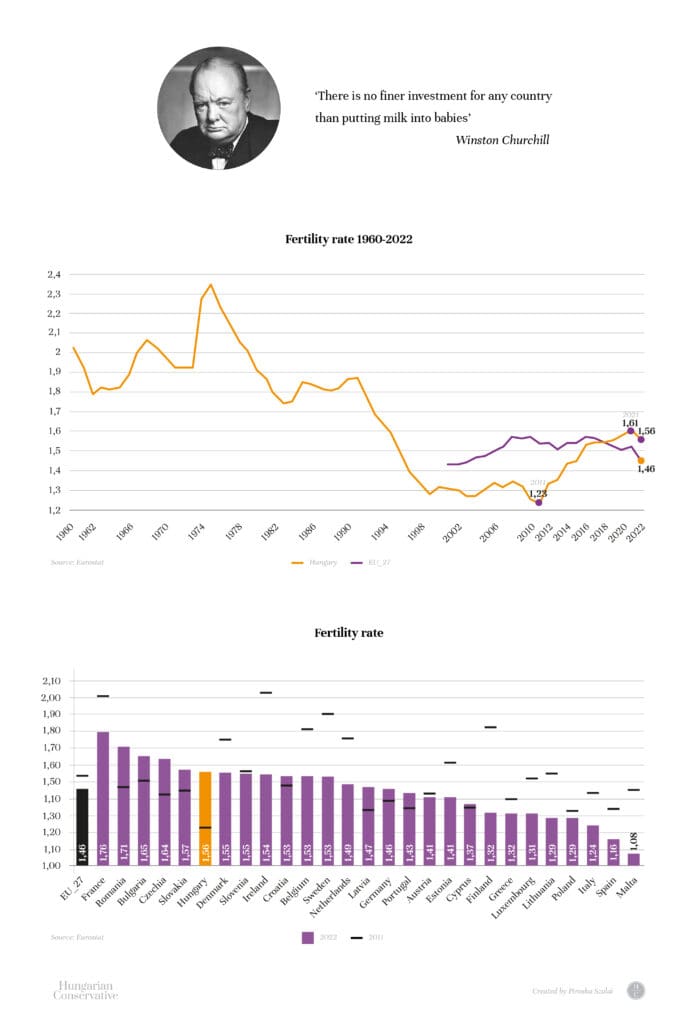

Fertility rates were very low across the regime changing countries. The lowest fertility rate in the history of the European Union was 1.09 in Bulgaria in 1997, but it was 1.13 in the Czech Republic in 1999, 1.19 in Slovakia in 2002, 1.2 in Slovenia in 2003, 1.22 in Latvia in 2001, Lithuania and Poland in 2003, 1.27 in Romania in 2002 and 1.28 in Hungary in 1999. You can read more on the subject here.)

We stopped falling in 1999 because the first Orbán government, formed in 1998, introduced a number of benefits and reintroduced the maternity allowance on 1 January 2000.

Benefits Quickly Changed

However, the left-liberal government that came to power in 2002 immediately abolished the latter and replaced it with market-based foreign currency loans, making life difficult for our families until 2015. Before 2010, Hungary had the second highest wage deductions among OECD countries, one of the lowest employment rates and the highest risk of excess poverty for those with children compared to those without. It was also decided to reduce the maternity allowance to two years.

Since the turn of the millennium and EU accession, living conditions and employment have improved in the regime changing countries, which has been accompanied by an increase in fertility. The only exception was Hungary, where the fertility rate reached a minimum of 1.23 in 2011.

Shift in Focus from 2010 to Support Childbearing

We have moved from our absolute fertility low in 2011, last in the EU, to sixth in 2022, with the highest growth in 2022. According to the latest Eurostat data, we moved up five places in 2022, the first year of the Russian-Ukrainian war, even though we had fewer children that year than in 2021. This fall was much smaller than in other EU countries.

Our annual decline of 0.05 per cent last year was one of the smallest, and 20 countries had a higher decline rate than Hungary in 2022,

which resulted in us moving up five places in the fertility rate ranking. Only five countries had a higher fertility rate than Hungary: France, Romania, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

In our country, the decline in the birth rate in 2022-2023 will be much smaller than in 2008-2011. It is also important to note that the number of women aged 20-40, the most active childbearing age, was more than 1.5 million in 2010 and has now fallen to just over 1 million 160,000, or by almost a quarter.

During last year’s price rises, families’ sense of financial security and prospects deteriorated, even if they were better off and not at risk of poverty. At such a time, more and more people are postponing or not having planned children. In fact, the number of postponers increases even as negative news about childbearing spreads. And positive news tends to increase fertility, which is reflected in the number of births after nine months. Therefore, I expect a significant improvement nine months after the announcement of the subsidized housing loan for urban residents at the end of October 2023, i.e. in the second half of this year. Fertility is pro-cyclical, i.e. it is already affected by news of potential changes in financial conditions.

Piroska Szalai is a labour market expert, a researcher at Economy and Competitiveness Research Institute of the Ludovika University of Public Service.

Mátyás Zsolt Varga is a journalist at Mandiner.

Related articles: