The Question of Jewish Self-Defence After the Collapse of the Kingdom of Hungary, 1919–1921

After the end of the First World War and the dissolution of the liberal Austro-Hungarian Empire that it brought along, a short-lived bourgeois radical government took leadership in the newly independent Republic of Hungary before the bloody communist putsch of March 1919. An invading Romanian army soon put an end to Béla Kun’s Communist Council Republic, only to be ousted by the Entente and give place to the counter-revolutionary forces of Miklós Horthy. All this happened in a little more than a year, and understandably Hungary was in a chaotic situation: depending the historical narrative inspected, the subsequent settling of political scores was either called ‘punishment of the unpatriotic revolutionaries’ or ‘murderous persecution of progressive elements’.[i] Objectively speaking, hundreds of unauthorized executions took place in the country, the victims of which were either ex-functionaries of the communist system or innocent Jewish traders and citizens. These murders—lately described as a wave of pogroms rather than state-ordered killings[ii]—became known as the White Terror, a term later often debated by the Right.

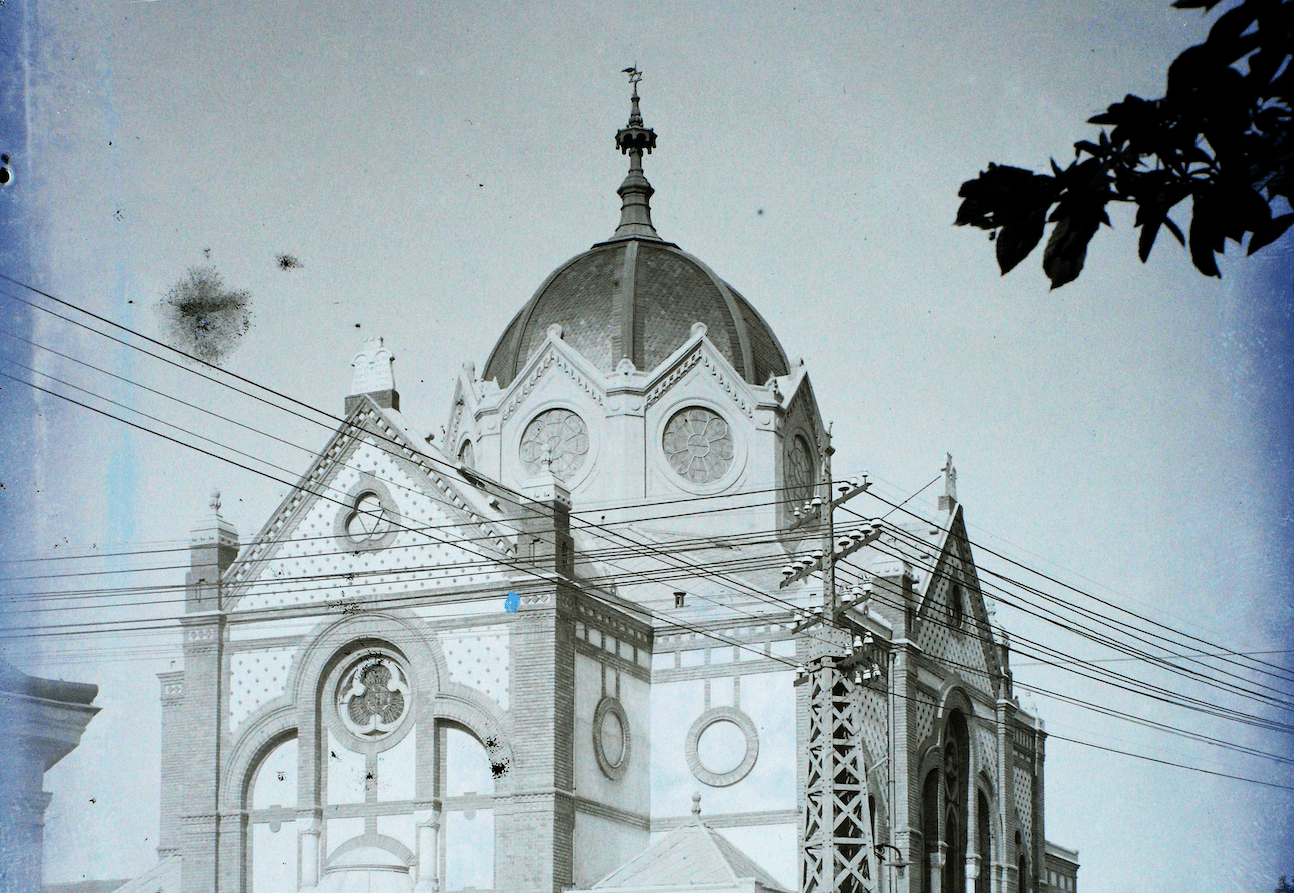

The academic literature on the subject generally agrees that around 400 persons fell victim to this wave of atrocities.[iii] How did the Jewish community react to these outbursts of mass violence? The Jewish elite placed its faith in the judicial system inherited from the Austro-Hungarian era, with the largest reform congregation, that is, the Pest neológ community – founding the Office for the Protection of the Rights of the Israelites.[iv] The Office was headed by a renowned lawyer, Géza Dombóváry junior who believed that the state will ‘provide just and law-respecting conduct’ for Jewry.[v]

The Office was open to any Jews who might have suffered grievances during the period, dully took record of each case and regularly filed legal complaints with the authorities. The legal results of the Office are easy to track, as numerous documents remain in the Budapest Metropolitan Archives and the Archives for Military History dealing with investigations started on behest of Dombóváry and his colleagues – and regularly halted by the authorities.

Not one of these documents demonstrate a single case of successful legal fight on the part of the Office. When two Jews were physically harmed on the streets of the capital, the complaint filed by the Office was rejected with the investigators without any sensible reasoning.[vi] A similar fate befell to Dombóváry’s objections raised against anti-semitic articles published in a certain newspaper: the Budapest court found that the tone of the articles ‘match[ed] the general feelings of the populace’ and could therefore incite no one any further.[vii] In another case, the court acquitted an anti-semitic polemicist from the charges of inciting ‘religious hatred’ with the reasoning that in his article he referred to Jews as a race, and not as a religious group.[viii]

‘Your son has disappeared, and I suggest you stop searching for him or else you will disappear as well’

The mother of László Harmat, an 18-year-old runner champion who was taken by unknown uniformed men from a Budapest training field similarly turned to the authorities in wain. After five weeks of desperate search for her son—and a number of letters sent to the military and state investigators (two separate branches of crime investigation at the time)—a man approached her in a café: she was told, in a morbidly polite manner, that ‘Your son has disappeared, and I suggest you stop searching for him or else you will disappear as well’.[ix] Even in cases where investigations were promptly launched, anti-semitic feelings poisoned the prosecution process as well. In the summer of 1921, a confidential letter of the Budapest general prosecution stated that the ‘widowed wife of Frigyes László […] reports the mugging and murder of her ex-husband. Please interrogate the widow and see if her husband was indeed robbed and murdered, and if Frigyes László was perhaps a Communist or a Jew’.[x] The words of the pogromists who assaulted Rabbi Zsigmond Büchler—who later reported the abuses suffered to the Offie—certainly clear any questions as to the reliability of the authorities: ‘You Jews are responsible for Communism […] Your blood will flow, and you will find no rest during day or night, even though we will always stand on the grounds of law and order. And if you will go to complain, they will listen to me and not to you’.[xi]

While the Jewish leadership—mostly belonging to the neológ branch of Judaism—took the approach of legal fight against the violence as described above, other Jewish groups, namely the Zionists followed a different, perhaps more pragmatic and practical tactic: spontaneous examples of Zionist self-defence have been documented. The mentality of self-defence has always been an essential part of the Zionist idea.[xii] This mentality was reflected in the Zionist weekly Zsidó Szemle, which in 1922 posed the following question to a Jewish youngster beaten by a mob: ‘Did you resist at all?’ In this case, it was probably inappropriate to ask: the teenager was attacked by eight men, and so his answer sounded perfectly reasonable: ‘How can you defend yourself against so many attackers?’[xiii] Yet, the mere fact that in 1922 a Jewish organ asked the very same question that sensitive historians might be hesitant to ask today reflects the real and contemporary need on part of some Jews to see efforts for self-defence against anti-semitism. The lack of organized Jewish self-defence was all the more painful because thousands of trained Jewish men returned from the war frontlines, and even among Jewish civilians the number of practitioners of martial arts were exceptionally high. It is also known that young Jews were the most frequent adherents of the romantic—and, according to many, outdated—tradition of duelling with the sword.[xiv] Put together, it can be factually stated that an outstandingly high number of Jews were capable of defending themselves, and in certain cases, such as the duellers, the number of Jews trained in the use of arms even exceeded those of the non-Jews.

Hungarian—and even Entente— authorities specifically disarmed Jewish households across the country

One of the reasons why many Jews did not use their weapons to defend themselves could be that the authorities, which paid great attention to disarming the populace after the two revolutions, believed that taking away the weapons of Jews—often accused of Bolshevik sympathies—was of paramount importance. Numerous archival documents attest to the fact that Hungarian—and even Entente— authorities specifically disarmed Jewish households across the country.[xv] Yet, as a British military observer noted, it was technically impossible to search every home and hideout across Hungary, and therefore, as this particular report believed, the results of such efforts ‘amounted to almost nothing’.[xvi] In addition, a great number of stolen First World War guns and hunting weapons were available on the black market all over the country.[xvii]

Unfortunately, not many cases of individual Jewish self-defence are known. A Zionist butcher stabbed a pogromist to death, and was later sentenced to prison in a court.[xviii] One memoir mentioned Jewish students who, during one of the regular antisemitic campus abuses, defeated their attackers with their classroom chairs.[xix] Zsidó Szemle wrote of policemen of Jewish origin who protected Jewish civilians against the atrocities,[xx] while a liberal Jewish weekly knew of at least a couple of incidents during which Jewish veterans, boxers or butchers successfully chased away anti-semitic attackers.[xxi] Jenő Freund, Zionist head of the Debrecen Jewish congregation, and a former duelling champion, beat up a man who insulted him on the street in 1921.[xxii]

But even if one did not intend to purchase weapons from the black market, which could have been a viable option for the mostly middle-class Jews, one could still have hired as a bodyguard any of the thousands of poor, jobless Christian war veterans looking for employment. We know of at least one Jewish household—from the provincial village of Kerekegyháza—which employed a Christian war veteran to protect their family during the summer of 1921.[xxiii] The Jewish owner of one of the country’s biggest newspaper portfolios similarly employed a Christian bodyguard who could successfully prevent his beating up on one occasion.[xxiv]

One might similarly look for humane behaviour on part of the Christian majority as a form of resistance to the pogroms, even if such examples hardly classify as ‘Jewish resistance’. Several heroic Hungarian Christian individuals stood up for their Jewish neighbours. During a Budapest murder committed by army personnel, one soldier suggested that perhaps they should not take the life of their victim. The soldier was quickly questioned by his comrades: ‘What do you want with these stinking Jews? We’ll hang you along with them! If you speak too much, I’ll shoot you right here and now!’[xxv] During a pogrom in the village of Izsák, some local Christians were beaten by the mob for having sheltered Jews.[xxvi] We also know of the case of Lieutenant István Plachner, who called for a doctor after his comrades cut the throat of a Jew. Plachner was later punished for his humane behaviour and received so many subsequent threats on his life that he chose to leave the country.[xxvii]

In summary of the inspected events, we can conclude that strikingly few examples of physical self-defence emerge from the documentation and accounts available on the years of these atrocities. The Hungarian Jewish elite placed heavy emphasis on the safeguarding of their rights instead, which is another form of self-defence according to Nathan Feinberg. However, these efforts failed in every single case examined, although not because of a lack of effort on the part of the Office for the Protection of the Rights of the Israelites, but because of the conscious sabotage of the rule of law exercised by the self-titled counter-revolutionary administration. Other Jewish groups saw the real and pressing urge for the physical protection of their communities. Perhaps the traditional Zionist interpretation of the general behaviour of Jewry – clearly illustrated in Chaim Nachman Bialik’s famous poem titled In the City of Slaughter[xxviii] – ,during the Russian pogroms, was overly critical. Such self-scourging criticisms did not emerge from the Hungarian Zionist press, but surviving victims of anti-semitic excesses were indeed questioned by Zionist journalists about their supposed lack of bravery and improper self-defence. While a few examples of physical resistance could be listed, the ‘objective and subjective difficulties’ of Jewish resistance—as listed by Shalom Cholawski—were probably present in the case of Hungarian Jewry as well.[xxix] One article dealing the Russian pogroms doubted the effectiveness of Jewish self-defence organizations even in the places where they were promptly called into effect.[xxx] Such questions are not raised by the Zionist Guard that operated in Hungary in 1918, but this—surprisingly effective—group was disbanded months before the White Terror. All in all, Hungarian Jewry was largely unprepared and defenceless against the wave of pogroms that overtook the country between 1919 and 1921.

[i] Ignác Romsics, ‘A Tanácsköztársaság és a Duna-melléki ‘parasztforradalom’’ [The Council Republic and the ‘Peasant Revolution’ in Eastern Hungary], Rubicon 22:2 (2011), 4–15.

[ii] Gábor Kádár, Zoltán Vági, ‘Hosszú évszázad: antiszemita erőszak Magyarországon’ [A Long Century of Antisemitic Violence in Hungary], in Randolph L. Braham (ed.): ‘A holokauszt Magyarországon hetven év után. Történelem és emlékezet [The Holocaust in Hungary after 70 Years. History and Memory]’ (Budapest: Múlt és Jövő, 2015), 76–110.

[iii] Romsics, ’A Tanácsköztársaság’.

[iv] For the documentation of the Office see Magyar Zsidó Levéltár [Hungarian Jewish Archives, from here on referred to as MZSL], I-E 1919 B 10/3.

[v] Géza Dombóváry (ed.), ’A pesti izr. hitközség által a Friedrich-kormányhoz 1919 júl. 2-án fölterjesztett jelentés [Report to the Friedrich-administration by the Pest Israelite Congregation on 2 July 1919]’ (Budapest: n. p., 1919), 1.

[vi] Hadtörténeti Levéltár [Archives for Military History, from here on referred to as HL], HM ELN C 1921 50128.

[vii] Budapest Főváros Levéltár [Budapest Metropolitan Archives, from here on referred to as BFL], VII.18.d-1922-05/0420, 7-8.

[viii] London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/3121/C/11/012/042/1, Hungary: Numerus Clausus including petition to the League and replies from the Hungarian Government, 1924/1988 no. judgement against Lehel Kádár and its English translation.

[ix] HL, HM ELN C 1920 100247.; Politikatörténeti Intézet és Levéltár [Institute and Archives for Political History, from here on referred to as PIL], 658.f.10/7., 9-10. A Polish Jew, abducted by the same armed men – probably belonging to the elite corps of the Hungarian army – later told Harmat’s mother what fate befell her son. He was taken to a military complex in Buda, where he was forced to eat beans from a bowl while being beaten with sticks. Every time he slowed down, the beating intensified, and so it went until he suffocated.

[x] PIL, 658.f.10/7., 26.

[xi] MZSL, I-E 1919 B 10/3, report on Albertirsa.

[xii] Stefan Wiese, ‘Jewish Self-Defense and Black Hundreds in Zhitomir. A Case Study on the Pogroms of 1905 in Tsarist Russia’ Quest. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History, 2012/3, http://www.quest-cdecjournal.it/focus.php?id=304#D, accessed on 22 September 2022.

[xiii] See the interview in Zsidó Szemle, 3rd March 1922.

[xiv] On the high presence of Jews in the field of martial arts and other sports, see István Hegedüs ‘Őrségváltás’ [Changing of the Elite] (Budapest: Stádium, 1943), 499. While an anti-semitic book, its data on the subject has not been questioned. On Jews and duelling, see Kálmán Mihály, ‘Cutting the Way into the Nation: Hungarian Jewish Olympians in the Interwar Era’, in Leonard Jay Greenspoon (ed.): ‘Jews in the Gym: Judaism, Sports, and Athletics’ (West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 2012), 127–128.

[xv] Central Zionist Archives, A129/8, report on pogroms without pagination; National Archives – Public Record Office [from here on referred to as NA], FO 371/7612, report on Hungary dated 22nd June 1922.

[xvi] NA, FO 371/7610, Memorandum Showing the Progress in Execution of the Military Clauses of the Treaty of Trianon, n. d. and Budapest Legation to FO, 10 April 1922. See also ibid., 371/7612, Report of British Representative on Hungarian Commission of Control, dated 7 June 1922.

[xvii] On the Hungarian government’s unsuccessful attempts to disarm the populace, see Dezső Nemes, Elek Karsai eds., ’Iratok az ellenforradalom történetéhez’ [Documents on the History of the Counterrevolution], vol. 1. (Budapest: Szikra, 1956), 180, 192–193. On the rural black market for guns and other weaponry, see a report in the 26 September 1920 issue of the far-right newspaper Szózat.

[xviii] See a summary of the case in the Socialist daily Népszava, dated 19 April 1925.

[xix] Géza Komoróczy (ed.): ‘‘Nekem itt zsidónak kell lenni’. Források és dokumentumok (965–2012) [A Jew I have to be here’. Sources and Documents, 965–2012] (Pozsony: Kalligram, 2012), 912.

[xx] Zsidó Szemle, 3 March 1922.

[xxi] Lajos Szabolcsi, ’Két emberöltő. Az Egyenlőség évtizedei, 1881-1931. Emlékezések, dokumentumok’ [Two Generations. The Era of Egyenlőség, 1881-1931. Memoirs and Documents]’ (Budapest: MTA Judaisztikai kutatócsoport, 1993), 287.

[xxii] See a report by the Transylvanian Zionist journal Új Kelet, dated 6 February 1921.

[xxiii] MZSL, I-E 1919 B 10/3, report on Kerekegyháza.

[xxiv] BFL, VII.18.d.1925.06/0064, 36.

[xxv] BFL, 20630/1949, 74.

[xxvi] MZSL, I-E 1919 B 10/3, report on Izsák.

[xxvii] See their stories in the 26-27 August 1924 issues of Esti Kurír.

[xxviii] ‘Come, now, and I will bring thee to their lairs / The privies, jakes and pigpens where the heirs / Of Hasmoneans lay, with trembling knees, / Concealed and cowering,—the sons of the Maccabees! / The seed of saints, the scions of the lions! … / It was the flight of mice they fled, / The scurrying of roaches was their flight; / They died like dogs, and they were dead!’ Ch. N. Bialik, ‘The City of Slaughter’, in Israel Efros (ed.): Complete Poetic Works of Hayyim Nahman Bialik, Vol. 1 (New York: Histadruth Ivrith of America, 1948), 129–143, here 138.

[xxix] Shalom Cholawski, ’The Jewish Partisans – Objective and Subjective Difficulties’, in ’Conference on Manifestations of the Jewish Resistance during the Holocaust, April 7-11, 1968. Synopses of Lectures’ (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1968), 6. Cholawski cited the lack of arms and training, the lack of outside assistance, the absence of organised Jewish resistance and the urban nature of Jewry (‘being out of touch with nature’) as possible difficulties.

[xxx] Wiese, ‘Jewish Self-Defense’.