The following is an article written by Orsolya Ferenczi-Bónis, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

Kiszehajtás’ (when girls dressed up a straw man in women’s clothes, carried it around the village and then threw it into water or burned it), ‘villőzés’ (when small groups of girls carried around decorated branches or trees called ‘villő’), fire ordination, Easter perambulation (walking the borders), ‘harmatszedés’ (collecting dew), and so on—in addition to egg-painting and sprinkling water, there are many folk customs and traditions associated with Easter that we have collected in our article.

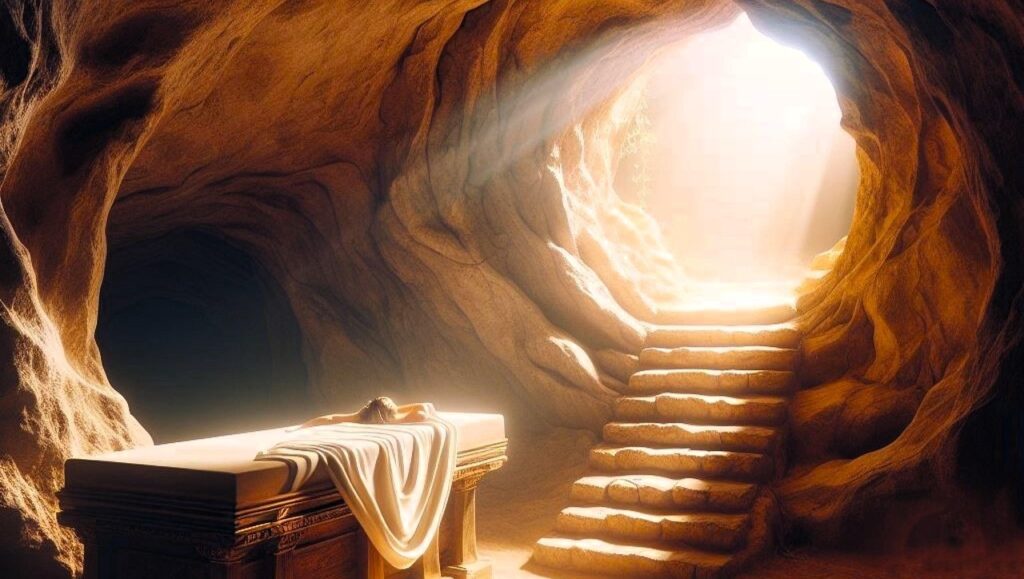

Easter is the most solemn celebration in the Christian world, commemorating the redemptive death on the cross and resurrection of Jesus Christ. In Judaism, Passover is celebrated at this time of the year, too, the meaning of which—‘to avoid, to escape’—is a reminder of the deliverance from Egyptian bondage. For a long time, the two feasts coincided, with Jesus and his disciples having the Last Supper on the eve of Passover. The First Council of Nicea in 325, however, regulated the Christian feast days, placing Christian Easter on the Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox. This date changes from year to year, so Easter is a movable feast. The spring equinox was a time of celebration of spring, the awakening of nature, and rebirth that goes back to ancient times.

The word Easter in many European languages, such as in English and ‘Oster’ in German, comes from the Teutonic goddess Ostara. The Hungarian word ‘húsvét’ refers to the resumption of eating meat after forty days of fasting (with ‘hús’ meaning ‘meat’, and ‘vét’, the noun form of the verb ‘vesz’, meaning ‘to take’, that is, ‘the taking of meat’), and also refers to the resurrection of Jesus Christ and the Holy Communion at Easter.

Palm Sunday is the last Sunday of Lent and the beginning of the Holy Week. In the Catholic Church, the Holy Mass on Palm Sunday begins with a procession to remember how Jesus was greeted by the celebrating crowds as he rode into Jerusalem on a donkey. The leafy boughs, broken from the trees and placed in front of his path, are represented by palms or catkin. Our ancestors gathered catkin on the Saturday before Palm Sunday, and after Mass they took the sacred branches home, believing they had special powers to prevent disease and protect against lightning. Another traditional Palm Sunday custom was the process of ‘kiszehajtás’: a straw doll dressed in women’s clothes, representing winter, was carried around the village and then thrown into water or burnt. On this day, not only was winter driven out, but spring was also brought in, a custom known as ‘villőzés’, during which willow branches were decorated and carried around the houses.

Our ancestors dedicated Holy Week to cleaning and tidying up their surroundings, following the renewal of nature.

Not only did they tidy up their own gardens, but they also cleaned up communal areas and tools such as ditches and wells.

On Holy Thursday, it was believed ‘the bells went to Rome’, so they stopped ringing only to be rung again on Holy Saturday. On these days, in the absence of bells, the ringing of clappers served as a warning of the services and also as a revival of the old noisy, evil-expelling customs. Good Friday, the day of Jesus’ death on the cross, was not only a day of strict fasting but also a day of a ban on work and weather forecasts. Then, on Holy Saturday, fire ordination was an ancestral custom. In the Catholic liturgy, the lighting of a new fire symbolizes the resurrection of Christ from the rock tomb. Easter Sunday, Christians’ biggest celebration, is the feast of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. For our ancestors, it was also a day of no cooking, no cleaning, and no driving out the animals.

Easter Sunday is linked to the custom of consecrating food, too. The food to be eaten that day, ham, bread, eggs, and wine, were consecrated in churches. It was believed that the crumbs of the consecrated food would protect livestock and stimulate crops, so they were later given to the animals or spread on the fields.

Folk traditions were also born from the Easter mystery plays: the Easter perambulation, or walking the borders, was a way of carrying around the news of Jesus’ resurrection. People went across the fields so that nature might also share in the Lord’s victory, that natural disasters be kept at bay, and that the harvest be plentiful. During the search for Christ, on Holy Saturday night, the whole community went around the crosses of the village, praying for the repentance of sinners, the absence of natural disasters, and a good harvest, and then they went in procession to the cemetery, where they prayed at the graves of their loved ones until dawn. During the procession of ‘harmatszedés’, that is, picking up the dew, villagers prayed in the village’s Calvary, turning towards the dawning sun, and then washed themselves in the dew.

Another custom associated with the Easter holidays was ‘mátkálás’ (with ‘mátka’ meaning ‘bride’), where two girls pledged eternal friendship, and ‘komálás’ (with ‘koma’ meaning ‘brother-in-law’), where godparents pledged kinship. It was also customary to send a gift basket, which was used to seal the adoption of the new kin.

The most characteristic Easter tradition on Easter Monday is sprinkling water, based on the belief in the purifying and fertility-enhancing power of water. In girls’ houses, sprinklers were offered food and drink and presented with red or decorated Easter eggs. The egg is a symbol of fertility, life, rebirth, and, in church symbolism, resurrection.

The Easter egg was originally dyed only red, a colour reminiscent of the blood of Christ shed for humanity.

Traditionally, natural materials were used to dye the eggs. The simplest way of painting was to cover the surface of the egg with a leaf and place it in a paste of onion or walnut shells, which naturally dyed the exposed surface of the egg, leaving the area of the covered surface clear and giving the shape of the leaf with a wavy edge. Waxing and scratching were also used to create shapes on the eggs, which were not stained by the paint, leaving the pattern clearly visible. A special solution was to make shod eggs, too.

Easter eggs could be a gift in many ways. As a symbol of the risen Christ, it served as a traditional gift from godparents to their godchildren, too, but it was also customary for the husband to cut the consecrated egg in two and eat one half for himself and the other half for his wife—ensuring that the two of them would always find the right path together.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.