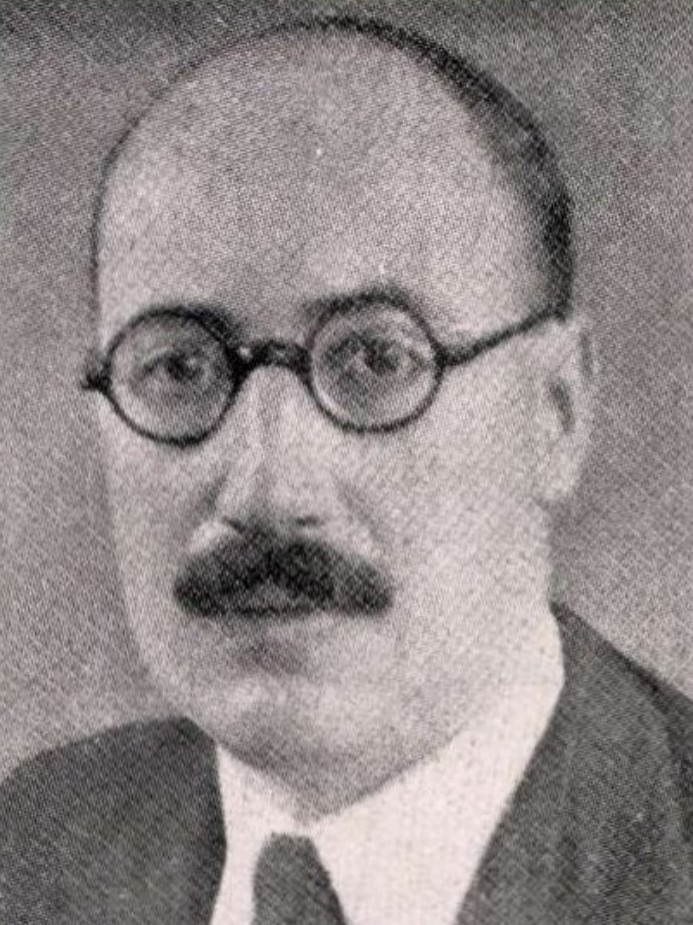

On 12 September 1949 lawyer Eduárd Landauer, CEO of the Royal Hungarian Automobile Club (KMAC) , was arrested. Landauer had been a well-known figure among the Budapest elite for decades, frequently appearing in the (scandal) columns of newspapers. His father, Béla Landauer, was a Jewish lawyer, writer, and politician who had previously worked for the Austro–Hungarian governorship in Bosnia and briefly served as a member of parliament before being arrested by the Communists in 1919.

Eduárd was born on 3 September 1898 in Sarajevo. Between 1916 and 1918, he served in World War I as a lieutenant and was discharged with an Officer’s Gold Medal for Bravery. He studied law in Budapest and began his legal practice in 1921. In 1923 he was sentenced to prison for a fatal duel. His personal life, wealth, and automobiles were frequently mentioned in the press, while the Arrow Cross Party publicly attacked him with antisemitic rhetoric. He joined KMAC in 1929, became its prosecutor in 1934, and was appointed chief prosecutor in 1935. At one point, he suspended his legal practice to work for major banks. He invested part of his wealth in rental properties. Fluent in five languages, he was divorced by the time of his arrest and had one child. Between 29 June and 23 September 1940, he served as a reserve officer in the Hungarian army in Kárpátalja (Carpathian Ruthenia, today in Ukraine). In 1944 he applied for and received the governor’s exemption from anti-Jewish laws, which allowed him to continue his legal practice, but during the Arrow Cross regime, he too was forced into hiding. Due to his Jewish origins, he was denounced and took refuge in the János Sanatorium.[1]

Although Landauer’s military tribunal case records have survived, his investigative file is much more incomplete. It appears that he was first denounced in May 1948 by Police Lieutenant Bernát Denhof, who accused him of having ‘served Imrédy, Szálasi, and the Germans throughout’—though what this actually meant remains unclear, as Landauer was certainly in hiding for his life during the Arrow Cross era. By 1957 Denhof was already living in Israel, but during the Rákosi regime, he had been a notorious and brutal interrogator for the secret police, serving as a political investigator in Kecskemét. His methods of torture were so extreme that they even provoked public protests from the Smallholders’ Party. The authorities investigated Denhof’s accusation against Landauer and ultimately found it unfounded.[2]

Somewhat later, the police of District I in Budapest received an anonymous report from abroad accusing Landauer of currency smuggling. As ‘evidence’, the report claimed that his son was studying in Switzerland, which must have been expensive. This accusation was also filed away without further action. By the summer of 1949, he was arrested in the wake of the Rajk case, but it appears that he managed to escape serious consequences even then.[3]

In September, however, Landauer was arrested again, and on 23 November 1949, the Ministry of Defence’s Military Counterintelligence Directorate compiled a summary of his case. According to this report, the investigation had determined that Landauer had been an American spy even during the previous war and that after August 1946, he had once again ‘been in contact with various intelligence agencies of the imperialists’.

Shockingly, throughout the trial, allegations persisted that Landauer had supposedly spied for the Allies during World War II. Although he denied this, and no concrete charges were ever formally brought against him, his alleged activities were repeatedly mentioned with disapproval. The report claimed that Landauer had resumed espionage because ‘he knew that due to his origins and political stance, he would not remain in his position for long, and anticipating his removal, he sought to secure himself “on the other side” as well.’

It is unclear whether ‘origins’ referred to his Jewish heritage or his relatively capitalist background—both meanings were possible in the terminology of the time.[4]

According to the report, in 1946, while serving as the executive secretary of KMAC, Landauer travelled to Austria, where he allegedly made contact with an agent of the American Counterintelligence Corps (CIC), a certain Beach, to whom he provided sensitive political information. This was followed by another meeting in April 1947, during which he reportedly shared details about Hungary’s automobile fleet, gasoline production, and the state of newly built roads. Further meetings allegedly took place in August 1947 and March 1948, with the latter involving the handover of a map detailing new road developments.

Additionally, in June 1947 Landauer was said to have established contact with Harry Le Bovit, an intelligence officer at the US Embassy, as well as Paul Marty, a ‘captain’ and the head of the Allied Control Commission in Budapest.

The report concluded with a peculiar statement: ‘The described facts are fully proven based on the suspect’s confession and the testimony of witnesses interrogated in the case.’ This was a strange assertion; as will be seen shortly, no actual evidence supported these claims. Nevertheless, according to the report, these allegations constituted ‘treason’ under Act III of 1930.

The investigation, conducted by the notorious Military Political Department (Katpol), included multiple testimonies from so-called ‘witnesses’. However, these individuals could hardly be considered witnesses, as they seemingly knew nothing about the case beyond their general acquaintance with Landauer.

On 12 October 1949 Miklós Pálinkás, an officer, stated that while Landauer had indeed travelled frequently to Austria: ‘I have no concrete knowledge of Dr Eduárd Landauer’s espionage activities.’ That same day, race car driver Endre Komlósi testified that Landauer often travelled abroad but admitted: ‘I had no concrete knowledge that Dr Landauer was in contact with foreign intelligence during his trips.’ He recalled that Landauer had once spoken privately with an American in Austria: ‘but I do not know what they discussed.’

Five days later a certain Károly Jakabfy testified that he had been present during a conversation between Landauer and Le Bovit: ‘During these occasions, no conversation took place between Landauer and Le Bovit that would relate to Landauer’s current criminal case, but I do not know how their relationship developed afterward.’ Finally, Gyuláné Mihók, a colleague of Landauer, testified as such: ‘I have no detailed knowledge of his foreign contacts.’

Landauer himself was interrogated by Katpol on 25 October. In an 11-page statement, he essentially repeated and signed off on the accusations outlined in the report, including the claim: ‘I accepted the task from the aforementioned American official.’ He even ‘confessed’ to espionage activities for the Americans in May 1940, recalling past conversations from nine years earlier in striking detail.

‘He made his confession under duress. He was subjected to various threats regarding his fiancée’

Landauer was subsequently interrogated by the military prosecutor’s office on 20 December 1949. This time, he fully retracted his previous confession: ‘I made my statement under psychological coercion due to my arrest; therefore, I do not stand by it.’ He admitted that he had met with foreigners in Austria but firmly denied the allegations: ‘It is not true that Beach instructed me to provide detailed information on my next visit. It is not true that during our conversation, I provided intelligence on Hungary’s automobile fleet, gasoline production, or the condition of roads, nor that I was given any task, nor that I was asked to obtain a map.’

He also explicitly stated that he had never been a spy during the war. However, when he was interrogated again on 9 January 1950, something had changed. It is unclear what transpired in the interim, but this time, Landauer requested that his retraction be disregarded and asked that his original confession at Katpol be considered his official testimony before the prosecutor’s office—in other words, he now declared himself guilty. The only personal detail he added was that he was solely responsible for supporting his 78-year-old mother.

As expected, the Budapest Central Military Prosecutor’s Office submitted the indictment on 12 January 1950. The military prosecutor put little effort into it—the text was essentially identical to the investigation summary. The first-instance trial was held on 14 and 15 January 1950 at the Budapest Military Tribunal, with the public excluded. The presiding judge, Béla Gadó, was a career lieutenant and a survivor of unarmed forced labour (munkaszolgálat). During the trial, Landauer strangely accepted the charges in the indictment—essentially pleading guilty—, but also stated that the indictment was not true, calling it ‘completely fabricated’. According to the minutes:

‘He did not engage in espionage either in the past or after the liberation. He made his confession under duress. He was subjected to various threats regarding his fiancée, and under this pressure, he decided to make a false confession and accept the consequences for a crime he did not commit.’

‘The entire procedure seemed like a hollow ritual’

In response, they played the recording of his statement made during the investigative phase, in which he had recited his confession. However, according to Landauer: ‘the record was made at a later time when he already knew the whole espionage story by heart. What was said on the record does not reflect the truth. He did not commit any crime and has nothing to regret.’

From this point on, the entire procedure seemed like a hollow ritual. After Landauer, they called to testify those individuals who had also been interrogated by Katpol, and they testified according to the statements they had made during the investigation. For example, Pálinkás stated that he ‘had no knowledge of the defendant’s espionage activities,’ and so on. Following this, Géza Kelemen, a military expert, testified that the information provided by the defendant constituted military secrets. The prosecution demanded the harshest penalty, while the defence called for a just verdict. Landauer added that he would appreciate it if the confiscation of his property were excluded from the sentence, as his mother was elderly and lived alone.

The court found Landauer guilty on all counts. As the verdict stated: ‘due to his public office, he came into possession of military secrets, which, at various times, but in short intervals and with unified intent, he communicated to unauthorized persons with the aim of making those secrets known to foreign state authorities, an act which severely harmed the interests of the Hungarian state.’ The verdict was based on his confession and the testimonies of the witnesses. The punishment was death by hanging and confiscation of property. The reasoning again included that Landauer had been an espionage agent during World War II: ‘During the war, he continuously provided information to American intelligence services regarding Hungary’s road conditions, car and fuel data (sic!).’

The verdict noted that Landauer admitted his crimes during the investigation, then retracted his confession, only to make another admission later. The court summarized Landauer’s words by stating: ‘The investigative process, and especially his concern for his fiancée, subjected him to such extraordinary torture that, under its influence, when he was provided with paper and writing materials during the investigation, he sat down and began writing a novel-like account of his actions, which became the basis for the confession document,’ and thus ‘he recorded events that never took place.’

However, according to the verdict: ‘the supplementary evidentiary process of the court… fully contradicted the defendant’s presentation, as it became clear that the defendant, during his questioning, gave clear, unambiguous, and coherent answers to the questions posed, and his confession was made in this context. This latter evidentiary procedure definitively established that no coercion was applied in connection with the defendant’s confession.’ Furthermore, the court argued that: ‘Since in similar cases, particularly with individuals like the defendant, material evidence is rarely left behind, the court can only conclude that the confession must have been made as a result of thorough consideration.’

This reasoning, of course, is entirely ridiculous: the fact that a recording was made of Landauer repeating his confession did not mean it was true, and no witness or evidence proved his guilt. Attached to the case materials were the ‘deliberation minutes’ from the Budapest Military Court, which noted that the court—consisting of Lieutenant Gadó, Lieutenant Colonel Gyula Fehér, Major György Tiborc, and Captain Endre Sárközy—unanimously found Landauer guilty and recommended the punishment according to the decision. Afterward, they ‘transformed’ into a ‘mercy council’ and unanimously concluded that Landauer was not deserving of mercy.

The verdict was accepted by both the prosecution and the defendant, but the defence attorney appealed against the defendant’s will. Although Landauer did not request mercy, the defence attorney, in case the verdict became final, requested clemency for him. In his brief and difficult-to-refute argument, defence attorney István László stated: ‘According to the data from the main trial, no material evidence was presented against the defendant, and the verdict is based solely on the defendant’s confession.’ During the second-instance trial held at the Military High Court on 16 May 1950, presided over by Lieutenant Colonel László Bajor, Landauer did not appear, despite being summoned, and was only represented by his attorney. The defence again presented the reasons for the appeal, but the court rejected them. The second-instance ruling only amended the first-instance decision by adding Landauer’s military demotion to the penal portion of the sentence. Landauer’s case was then forwarded to President of the People’s Republic of Hungary Sándor Rónai, who rejected the clemency request on 25 May. According to the minutes, on 27 May, at 6:30am, Landauer was informed that his petition had been rejected and the sentence would be carried out in one hour. Landauer’s death was pronounced at 7:10am.

‘They have ways to make me rot in prison without a verdict, but first, they will make me go through the various methods of Andrássy Avenue 60’

Another detail can be added to the case based on the documents from the State Security Services Historical Archives. On 30 September 1950 Landauer’s secretary, Florence Mátay, was also arrested in connection with the case. She was sentenced to six years in prison for espionage, but in her case, entirely different individuals were named as her foreign contacts. Later, Mátay was employed as a cell informant, and based on this, she requested a pardon for her sentence. In her petition, she stated that during the investigative phase of her case, she was subjected to ‘physical and psychological coercion’ at Andrássy Avenue 60, and the head of the secret police Gábor Péter personally told her: ‘If I sign the report, I will be convicted; if I don’t sign it, they still have ways to make me rot in prison without a verdict, but first, they will make me go through the various methods of Andrássy Avenue 60.’[5]

All of this helps place Landauer’s retracted confession and the threats made against his fiancée in context. Although it is not entirely clear why his trial was necessary, earlier reports show that someone had already ‘singled him out’ years before. His secretary was extensively interrogated about Landauer’s financial situation and the luxury cars he owned; it even seems possible that someone had set their sights on these vehicles. The relevant documents also reveal that Mátay had been recruited earlier to monitor Landauer, and her handler—who was also her lover and the driving force behind the case—was Police Major György Kardos, a survivor of the Theresienstadt concentration camp.[6]

A posthumous justice took 42 years: on 28 May 1992 the Military Council of the Budapest Court declared Landauer’s death sentence null and void.

[1] For his biographical data see: Budapesti Ügyvédi Kamara Irattára, Budapesti Ügyvédi Kamara Ügyvéd Jelöltek Jegyzéke, XII. vol. 10933. no, p. 726; and Budapest Főváros Levéltára, IX.282.b. 6576; see also his testimonies: Hadtörténelmi Levéltár (HL), BKB Katf. 019/1950; and KB 05/1950. For the story of his hiding during the Holocaust, see: Szabadság, 23 March 1946, 3; and Állambiztonsági Szolgálatok Történeti Levéltára (ÁBSZTL), 3.1.9. V-113114. 22.

[2] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.9. V-38928. 4., 8.

[3] Ibid, 9.

[4] For all his trial papers see: HL BKB Katf. 019/1950; and KB 05/1950.

[5] ÁBSZTL, 2.1. VII/26 (V-142808). 6, 23., 27.

[6] ÁBSZTL, 2.1. VII/26-b (V-36043). 26–28, 31, 37. For Kardos and Mátay see: Mező Gábor, ‘Héja-nász a Katpolon: Kardos György és ügynöke, Ignotus Pálné halálos viszonya’, Pesti Srácok, 17 Dec 2017. https://pestisracok.hu/heja-nasz-katpolon-kardos-gyorgy-es-ugynoke-ignotus-palne-halalos-viszonya/

Related articles: