This article was originally published in Vol. 4 No. 2 of our print edition.

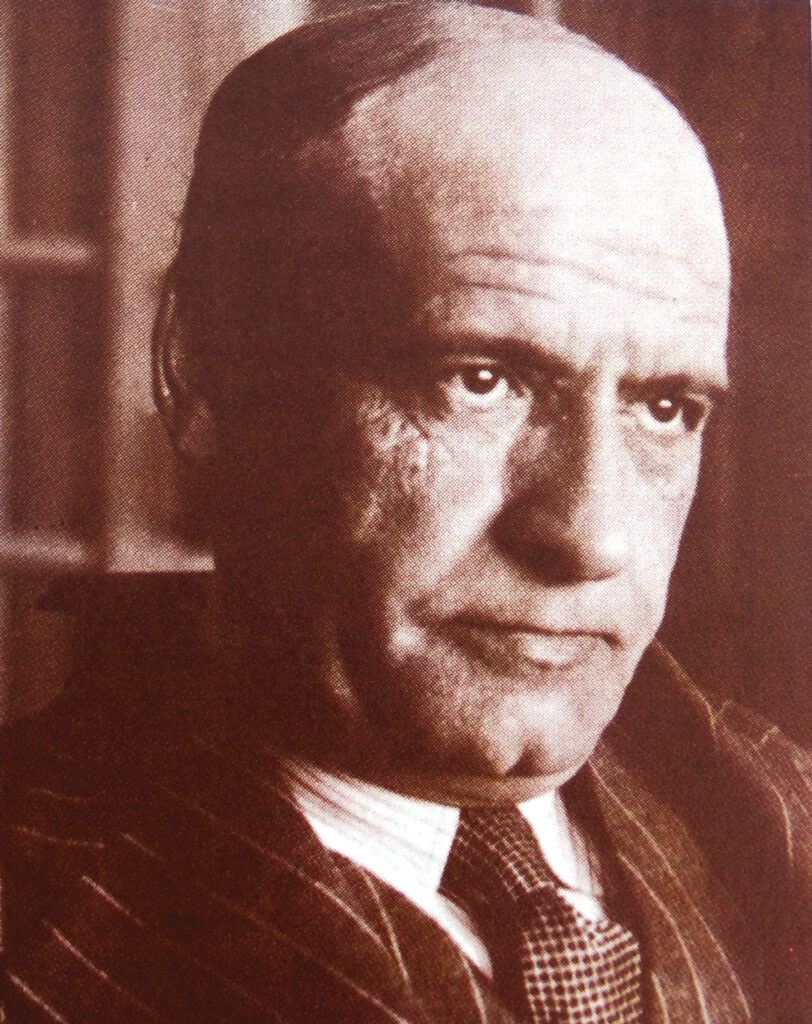

The Contemporary Relevance of José Ortega y Gasset (1883–1955)

José Ortega y Gasset (1883–1955), arguably Spain’s most distinguished modern philosopher, is mostly known outside the Spanish-speaking world for The Revolt of the Masses (1929), an analysis of what he called ‘triumphant plebeianism’ which a hundred years later, in the midst of debates about ‘populism’ and the tension between liberty, equality, and equity, continues to throw light on contemporary social and political developments.1 Ortega was a polymath who, in a lifetime of thinking, lecturing, and writing, left few subjects untouched. In an era of specialization, he was self-consciously a hangover from the days of the Enlightenment when thinkers aimed at a vision of the whole. In addition to what he called his philosophical anthropology, he also wrote about history, literature, the arts, the sciences, and education.

Like his fellow liberal Alexis de Tocqueville a hundred years earlier, Ortega saw democracy as the best form of government currently available, while also fearing that it would lead to rampant egalitarianism and the tyranny of the majority.2 He attributed the ‘mass society’ which he set out to analyze in The Revolt of the Masses to the Industrial Revolution, the huge rise in the population of the economically advanced world, and the concentration of people in large cities. He welcomed the way this had freed the working class from servitude, giving it a new vigour and involving it in political life, but feared the mentality that el hombre medio (the average man) in this society had acquired. The average man, he felt, had a strong sense of his rights, but no idea of corresponding duties. He saw himself as entitled to all the benefits of modern civilization but did not understand the effort that went into producing these and the need for restraint when pressing his demands. El hombre medio, Ortega said, with more than a hint of patrician disdain, was a niño mimado (a spoilt child), guilty of Nietzschean ressentiment, that sense of one’s own inferiority which leads one to envy and despise the more successful while doing nothing to improve oneself. It was this that was so easily exploited in the interwar years, he felt, by the two enemies of liberal democracy: fascism and communism.

The Inevitability and Necessity of Elites

In Ortega’s view, what the majority needed was an able minority to guide them, one which was trustworthy and which they trusted. He saw the nature of its elite as the main determinant of a society’s culture and wellbeing. An ineffective elite left a country without a backbone. This had been the main theme of his plea for a radical regeneration of his own country in his 1921 book España invertebrada (Invertebrate Spain).3 The main way to achieve this, in his eyes, was through the development of the kind of clerisy that Coleridge had first advocated in the early nineteenth century, conceiving of it as a group including clergy, schoolmasters, artists, and intellectuals. This idea was taken up later in the century in a variety of ways by John Stuart Mill, Thomas Carlyle, and Matthew Arnold, and in the next century by the poet T. S. Eliot, who saw the role of this elite as the preservation, against an indifferent mass society, of a civilization’s ‘high culture’, and in France by Julien Benda who, from a very different political perspective, demanded in his book La Trahison des clercs (The Treason of the Intellectuals) the replacement of a current elite which he felt had rejected Enlightenment values.4

Ortega similarly saw the liberal or intellectual professions, insofar as they were independent of the state, as a key element of this elite. They might not have their fingers directly on the levers of power, but would influence its exercise through their understanding of the subsuelo histórico (historical subsoil) of a society, and their ability to move beyond the matters of the moment to see how the destiny of a society might be proactively shaped. Ortega also felt that both the ruling and non-ruling parts of the elite would benefit from taking over the better qualities of the old aristocracies: self-control, a sense of duty, and noblesse oblige.5

This belief in the centrality of elites in explaining the success or failure of a society was shared by many writers in other European countries of the same period. In 1943, the American political theorist James Burnham grouped four of these—Gaetano Mosca, Georges Sorel, Robert Michels, and Vilfredo Pareto—under the name of ‘Machiavellians’, as thinkers combining a desire for freedom with a distrust of utopianism and a deep sense of realism.6 Mosca, like Ortega, believed that whatever form societies took—whether democracies, single ruler dictatorships, or would-be socialist utopias—they would all be led by a minority ruling class and that it was the nature of this class that largely determined the course of history in that society. Political science, Mosca argued, was essentially the study of such ruling classes. Michels believed that all organizations, not just states, inevitably gravitated towards minority rule, calling this ‘the iron law of oligarchy’. Pareto made similar distinctions to Ortega’s about the roles of governing and non-governing elites. Ortega, however, developed his ideas on elites separately from this group of thinkers, his only contact being with the German-Italian Michels, who greatly impressed him as a young man, during his university studies in Germany.7

Educating the Elite

Ortega’s image of what members of his ideal elite should be like derives from his wider philosophy. His spells at German universities made him initially a fervent neo-Kantian who, seeing the world through the lens of transcendental idealism, believed in the objective reality of the Platonic triad of truth, goodness, and beauty, and that this should form the basis of one’s life and education. Although continuing to revere Plato—he once wrote that it was essential for the sake of cultural transmission that at least a few thousand in a country must have read him—he soon turned his back on neo-Kantianism, falling under the influence of Husserl’s phenomenological approach to philosophy and of perspectivism.8 This led him to focus on the empirical, psychological, and historical, and on the individuality of human beings, all of which he summed up in what became the core phrase of his philosophical anthropology, ‘I am I and my circumstance’.

By this he meant that human beings were determined by their circumstances—their location in time and space, their generation, and their immediate background—but, having understood the limitations circumstances impose and the freedoms they allow, people are also capable of creating something new. Out of this emerges Ortega’s injunction to make a ‘project’ of one’s life or, as he often put it, to become ‘a novelist’ of oneself.9 This is what ‘the average man’, unable to see beyond the dominant clichés of his time, was unable to do, but which members of the minority need to do, so that they make something of their lives and leave behind achievements that will benefit the rest of society. Although when talking about ‘average men’ Ortega was mainly referring to the ‘mass man’ of a ‘mass society’, there were also ‘average men’ within the minority, whom he called ‘pseudo-intellectuals’, people who live in a world of ideas that have turned into dogmas, and sabios ignorantes (the ignorant learned), unable to see beyond their specialisms.10

‘Human beings were determined by their circumstances—their location in time and space, their generation, and their immediate background’

A key role of the teacher in this situation was not just to ensure that future members of the elite had the knowledge of their environment, and especially its historical context, necessary for them to understand the opportunities and limitations facing them, but also to help them interrogate the huge web of beliefs into which, by virtue of living in a particular place and time, they were unconsciously being inducted. This was not necessarily in order to reject these beliefs, but merely to be aware of them. The teacher’s role was to promote the habit of searching, questioning, challenging, and unsettling, and to do so in a Socratic way that, by revealing a student’s ignorance, stimulated his or her desire to learn more.11

The Mission of the University

What did this mean in practice? In the year after The Revolt of the Masses, Ortega published the other work by which he is perhaps best known today: Mission of the University (1930).12 Although focused mainly on Spain’s university system, it raises general issues about the purposes and priorities of all universities. Mission of the University shared with Cardinal Newman’s The Idea of a University (1852), Karl Jaspers’s The Idea of the University (1959) and Michael Oakeshott’s major essays on the university the idea that the core purpose of the university was the provision of a liberal education, seen as an induction into what Oakeshott called the major ‘languages of human understanding’.13 Ortega and Jaspers, in recognition of continental European realities, differed from Newman and Oakeshott in seeing universities as having a major role in professional education, while insisting that a core element of liberal education be provided to all.

Ortega saw the weakness of current Spanish universities as arising from the lack of a sense of what the university was trying to achieve. The least clear course, in terms of purpose, was cultura general (general culture) which all students followed and which had fallen into desuetude. This course had its origins in the liberal education universities had provided in the Middle Ages, and it was the absence of the modern equivalent of such an education that was producing an elite incapable of showing the leadership that ‘average men’ desperately needed. Ortega’s solution was to place a ‘Faculty of Culture’ at the heart of the university’s educational programme. A new version of cultura general would introduce students to the major disciplines necessary for understanding oneself, one’s environment, and one’s past: philosophy, history, sociology, and the sciences. The focus would be on knowledge and the key principles of these disciplines, not on promoting a particular set of values and beliefs.14 The university would also distinguish clearly between its research and teaching functions, and send a strong message that the purpose of a first degree was not to produce researchers, but broadly educated people capable of taking up positions in the world.

Despite scepticism about educational institutions being major agents of change, Ortega hoped that a reconstructed university might provide Spain with an intelligentsia better able to exert a beneficial influence on its future development. This was particularly important, he thought, at a time when parts of the intelligentsia, through esoteric experiments in the arts and a fascination with irrationalism, were making themselves incomprehensible to the rest of society in ways that intellectual giants in the past like Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Descartes would never have contemplated doing.15

A Postgraduate Finishing School for a Future Elite in the Rocky Mountains

Unexpectedly late in life, Ortega had an opportunity to develop specific plans for the kind of university education he favoured. This was not in Spain where, having left during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and returned after 1945, he was reluctant to take up any official position under the Franco regime. Much of his time was spent giving lectures in other countries, and it was on one of these visits—to Aspen, Colorado, in the Rocky Mountains—that he was invited to draw up plans for a postgraduate institute for the humanities.16 The Aspen Institute still exists, but with a wider remit that differs from the one Ortega envisaged.

The purpose of the institute, as Ortega saw it, would be to prepare postgraduate students for future membership of the US governing elite, making clear to them that this was its intention. To this end, and showing Ortega’s continuing respect for the educational legacy of ancient Greece, the institute would be designed with both Attic and Spartan features. The academic programme would be based on the different elements of cultura general, including the sciences, outlined in Mission of the University, but with even more stress on how the human condition can be understood synthetically through the interaction of different disciplinary approaches. The institute’s library would have a relatively small number of important and carefully selected books, and the focus would be on learning how to use these with care. As part of the Attic strand of the programme, teaching methods would have included the Socratic. Students would also be required to attend summer conferences where they would be exposed to outside speakers with opposing points of view.

The Spartan element of the programme was its pervading asceticism and sobriety. The institute would have few comforts and the winter climate would have to be endured. Students would have to test themselves in physical exercises and there would be a requirement for physical work. Ortega had recently seen students at Hamburg rebuilding their own university, which had been destroyed during the war. At Aspen, to emphasize their responsibilities and stiffen their endurance, they would be required to build roads, bridges, or houses instead.

The Limitations of Education in Ensuring That Elites Govern in the General Interest

Ortega was well aware of the deficiencies of elites, whether the aristocratic and clerical ones of Spain or those in other states, both democratic and authoritarian. The education he was proposing for future elites was designed to limit these deficiencies. There is little awareness, however, in his writings, of the reasons why even an exemplary education might not be sufficient to prevent an elite governing in ways contrary to the general interest, or how this might be combated. A recent book outlining the characteristics of ‘A Good Education’ saw education as ‘the primary determiner of the future of society’.17 If it is, as George Steiner used to ask, why did so many beneficiaries of the best humanist education Europe could offer (an education Ortega knew at first hand and valued), some with doctorates (and one with two), end up deeply involved in the administration of the Holocaust?18 If it is, why did some of the world’s greatest educators—Plato, Aristotle, Seneca, and figures of the Enlightenment—fail so spectacularly in turning their pupils—the rulers of Syracuse, Alexander of Macedon, Nero, and Prince Ferdinand of Parma, respectively—into philosopher kings?19 If it is, why in many Western countries did the largely traditional education many future intellectuals received at school in the last decades of the twentieth century fail to stop them turning into today’s censorious radical elite, preoccupied with managing the hierarchies of privilege and oppression it has imagined, antithetical to nation and tradition and keen to impose its dogmas on the majority?20

If education is much less a ‘primary determiner’ than some may think, what alternative ways are there of trying to ensure that elites govern in the general interest? Ortega’s ‘Machiavellian’ contemporaries, realists distrustful (as he was) of education for civic virtue, looked elsewhere for the answer. For Pareto, two approaches were needed. First, an elite should be self-renewing, with continual movement of people both out and in, making the emergence of a hereditary meritocracy less likely. Second, an elite needed a counter-elite sufficiently influential to force it constantly to re-examine itself.21

For a counter-elite to operate effectively, freedom of expression is essential, and it is an indication of their concern to nip in the bud any emerging counter-elite that so many supposedly ‘liberal’ Western elites and their governments seem increasingly keen on restrictions on this freedom at the present time. Ortega did not write about counter-elites as such but saw the benefit that came from the circulation of opposing views. He was also very conscious of all the unexamined beliefs one absorbed from one’s environment and, while accepting the desirability of their transmission, of the need to challenge them when necessary. This was especially true when confronting ‘pseudo-intellectuals’ who, instead of searching and questioning, enclose themselves in their own little worlds of dogma.

Ortega’s own approach as educator, he told his students, was that of someone who, provoked by the sight of a still and silent pond, starts throwing little stones into it, in order to unsettle the ‘fictitious calm’ of the reflection in it of the clouds floating across the skies above.22 It is an image which lingers in the memory and as an educational device—Ortega calls it la pedagogía de la contaminación (the pedagogy of contamination)—a stimulus to puncture ideological monocultures wherever one finds them restricting thought and doing harm. As an encouragement to future members of an elite to be aware of the dangers of dogma and groupthink, both in others and among themselves, it offers hope that even if education may not be ‘the primary determiner’ of the performance of an elite, it still has a crucial role to play.

NOTES

1 José Ortega y Gasset, La rebelión de las masas (1929), in José Ortega y Gasset, Obras Completas, Volume IV (Santillana, 2005), 349–505. The dates of publication of the ten volumes of the Obras Completas (hereafter OC) are: I and II (2004); III and IV (2005); V and VI (2006); VII (2007); VIII (2008); IX (2009); and X (2010). References below to items from the OC used in this article give the title and date of original publication, writing, or delivery, alongside the OC volume and page numbers. La rebelión de las masas has been translated into English as The Revolt of the Masses (W. W. Norton, 1994).

2 Ortega, ‘Tocqueville y su tiempo’ (1951), OC X, 362–366.

3 Ortega, España invertebrada (1921), OC III, 421–512.

4 Ben Knights, The Idea of the Clerisy in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 1978); Nicholas Tate, The Conservative Case for Education (Routledge, 2017), 51.

5 Ortega, La rebelión de las masas, OC IV, 411–412, 433.

6 James Burnham, The Machiavellians (Putnam, 1943).

7 Jordi Gracia García, José Ortega y Gasset (Santillana, 2014), 69.

8 Oliver Holmes, ‘José Ortega y Gasset’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2022 Edition, ed. Zalta, E. N.); Ortega, ‘Discurso para los juegos florales de Valladolid’ (1906), OC VII, 85–86.

9 ‘I am I and my circumstance’ is explored in the three following major works: Ortega, Ideas y Creencias (1940), OC V, 655–685; Historia como sistema (1941), OC VI, 43–81; El hombre y la gente (1949–1950), OC X, 137–326.

10 Ortega, ‘Democracia morbosa’ (1917), OC II, 274–275; La rebelión de las masas, OC IV, 408, 439, 444.

11 Ortega, ‘La pedagogía de la contaminación’ (1917), OC VII, 685–691.

12 Ortega, Misión de la Universidad, OC IV, 529–568. An English translation is available: Ortega, Mission of the University (Routledge, 1991).

13 John Henry Newman, The Idea of a University, ed. Frank M. Turner (Yale University Press, 1996); Karl Jaspers, The Idea of the University (Peter Owen, 1960); Michael Oakeshott, ‘The Idea of a University’ and ‘Universities’, in ed. Timothy Fuller, The Voice of Liberal Learning (Yale University Press, 1989), 95–135.

14 Ortega, Misión de la Universidad, OC IV, 535–542, 550–551, 559. John Stuart Mill, by contrast, saw the transmission of ‘General Culture’ in universities as a means to ‘moral indoctrination’, at least from the perspective of Maurice Cowling in Mill and Liberalism (second edition, Cambridge University Press, 1990), 113–117.

15 Ortega, ‘Apuntes sobre una educación para el futuro’ (1953), OC X, 390; ‘El intelectual y el otro’ (1940), OC V, 625–626; ‘Cosmopolitismo’ (1924), OC V, 202–203; ‘En el centenario de una universidad’ (1932), OC V, 735–745; Misión de la universidad, OV IV, 533.

16 Ortega, ‘Apuntes para una escuela de humanidades en Estados Unidos’ (1949), OC X, 44–51.

17 Margaret White, A Good Education. A New Model of Learning to Enrich Every Child (Routledge, 2018); reviewed by Nicholas Tate, International School (Winter 2022).

18 George Steiner, In Bluebeard’s Castle: Some Notes towards the Re-Definition of Culture (Faber and Faber, 1971), 69; Michaël Prazan, Einsatzgruppen (Éditions du Seuil, 2010), 109; Ortega, ‘La universidad española y la universidad alemana’ (1906), OC I, 63–86.

19 Elisabeth Badinter, L’Infant de Parme (Fayard, 2010).

20 On the late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century progressive elites, mostly in the USA and UK, see among others: Christopher Lasch, The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (W. W. Norton, 1994); Michael Lind, The New Class War. Saving Democracy from the Metropolitan Elite (Atlantic Books, 2020); David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere. The New Tribes Shaping British Politics (Penguin Books, 2017); Roger Eatwell, and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt against Liberal Democracy (Pelican, 2018); Matthew Goodwin, Values, Voice and Virtue. The New British Politics (Penguin Books, 2023).

21 Burnham, The Machiavellians, 53, 82, 153–155, 183–185.

22 Ortega, ‘La pedagogía de la contaminación’, OC VII, 691.