Hungarian Conservative has launched a ten-part series of articles on the past decade and a half of the Hungarian economy and society, titled ‘Revealing the Facts’. Rather than looking at a lot of different, isolated data it is worth providing an overview, comparing and analysing trends over time, in order to understand the details. The first article focused on the history and context of inflation. This second article provides insights into employment trends in Hungary between the late 1940s and the present day.

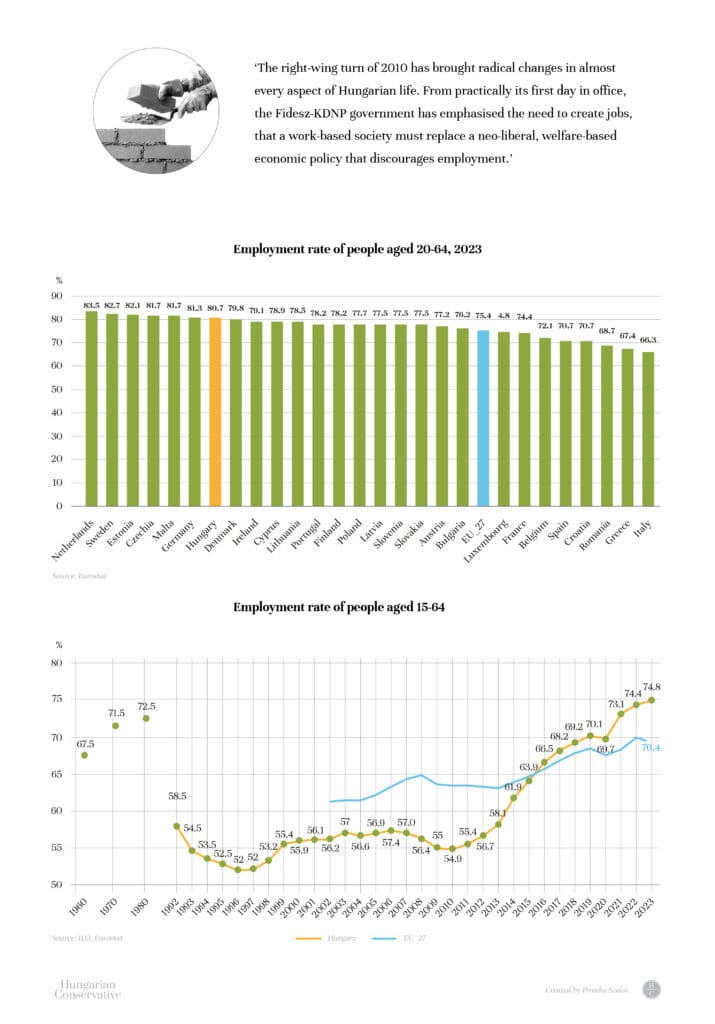

The second decade of the 21st century has seen an unprecedented expansion of employment in our country. From the low point of 2010, almost every aspect of our labour market has improved, breaking all records. In 2023, on average, 4 million 724 thousand people were working in Hungary and only 203 thousand were unemployed. Never before have so many people worked in Hungary. The employment rate for 20–64-year-olds exceeded 80 per cent, and the unemployment rate was 4 per cent, which is considered full employment. We are now the seventh best performer in the EU on both indicators, with the second highest improvement between 2010 and 2023.

Hungarians are particularly sensitive to whether they have a job, a livelihood that allows them to provide for their families in dignity, and whether they feel that this job is stable or whether they feel at serious risk of losing it. In fact, there is a well-known saying in Hungary: ‘if there is work, there is everything.’ We spend most of our lives preparing for our vocation and then practising it. A good job or profession is not a constraint and even if you work hard, it is not considered slaving away.

St Benedict, the principal patron saint of Europe, spoke of the dignity of work in his Regula Sancti Benedicti as early as the 6th century. A thousand years later, both Luther and Calvin extended the concept of vocation to all human work. Only Marxist ideology, born in the 19th century, is based on the idea of class struggle, on the opposition between the capitalists and the working class. By imposing a class-struggle approach that forces us into slavery, we weaken, not strengthen, the labour market and the economy. Moreover, our pension and social security systems are only sustainable if many people are in work and if incomes are rising.

A Little History

In Hungary, when the Communists came to power in the late 1940s, they set themselves the goal of full employment, which meant employing women. They achieved this by severely punishing unemployment, calling it ‘social parasitism’ (‘közveszélyes munkakerülés’ in Hungarian), a crime. This criminalization was part of the law until 1989.

As a result, 67.5 per cent of people aged 15–64 were working in 1960, including a third of women in this age group. The rates continued to increase until the 1980s, with young people staying in school longer and starting to work later, and women having almost full employment until the age of 55, when they reached retirement age.

Between 1989 and 1992, after the change of regime, one third of jobs were lost in Hungary; according to some estimates, as many as one and a half million. On the one hand, more than half a million people became unemployed, and the number of people retiring before retirement age, disabled pensioners and other inactive statuses multiplied; on the other hand, it became almost impossible for young people to find work after completing their education. No other country that underwent a system change has experienced such a decline in employment. For more than two decades, the loss of a job became the most frightening threat and the least manageable risk for the Hungarian population. And an attitude among young people became widespread: ‘I don’t want to grow up and start my own life because I don’t know how I’m going to make a living.’

The lowest level of employment in Hungary was recorded in 1997, when only 3.6 million people were in work.

Then, under the first Orbán government (1998–2002), the number of people in employment increased by almost 300,000, and the figure of 3.9 million remained stagnant for years.

After 2002, many real economic indicators stagnated or worsened, which unfortunately made us one of the few countries in Europe that did not benefit from the transatlantic economic expansion that lasted until 2008; even our employment rate started to decline in 2006, while the majority of EU countries—even the rest of those that joined in 2004—were still on an upward trend, and we were overtaken by all other Central European countries in the years 2004–2008.

From 2007 onwards, our employment rate for men was the lowest in the EU, and for women it was only above that of the Mediterranean countries. It is fair to say that the global economic crisis of 2008 had a more negative impact on men’s employment in our country than on women’s, and in many families, women became the breadwinners during this period.

How is it possible that the crisis of 2008 already had an impact on the Hungarian labour market in 2006? The figures show that the most destructive effect on the Hungarian labour market was not the global economic crisis, but the flawed economic and social policies of the time. The result was tragic: by 2010, the year of the change of government, we had become a laggard in almost all areas, both in regional competition and among EU countries.

The living standards of Hungarian families had fallen catastrophically, with almost a third of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2010. This was compounded by higher unemployment rates than the EU average and low wages in predominantly low value-added jobs.

A Turnaround after 2010 Towards a Work-Based Society

The right-wing turn of 2010 has brought radical changes in almost every aspect of Hungarian life. From practically its first day in office, the Fidesz–KDNP government has emphasized the need to create jobs and that a work-based society must replace a neo-liberal, welfare-based economic policy that discourages employment.

The change of government in 2010 brought a radical turnaround in all areas of life, but the long overdue tangible results were not easy to achieve. The right-wing government was only able to create a work-based society in several stages, while the impoverishing measures previously introduced by left-wing governments to attempt to stimulate consumption, namely foreign currency loans, caused an increasingly serious livelihood crisis.

At first, nearly 470,000 unemployed people searched for work, while the tax system set up by the left did not encourage employment at all, as the employers’ social contributions were high, making it a major expense to hire a new employee. Furthermore, the personal income tax was also high, but more on that in a later article. Also, in many cases, workers received part of their income ‘in the black’ because of the two-rate tax system—the second rate already affected those on below-average incomes.

The real change came after the government introduced the flat tax system and gave employers more incentives to expand their workforce and to employ legally. Alongside the change in the tax system, employment incentive schemes, in retrospect, proved effective, such as the rule that investment grants in certain EU tenders could be awarded to only those who committed to increasing their workforce.

In addition to encouraging employers to take on workforce, another key task of the government was to create jobs:

the right-wing administration set itself the goal of creating one million new jobs until 2020.

And this target was met: one third of the increase came from a reduction in the number of unemployed and two thirds from a reduction in the number of inactive people under 65.

Not Everyone Got a Job Straight Away

This has not been an easy task for the Orbán government, as job creation has proven to be a time-consuming task and Hungary’s left-wing economic policies had led to a prolonged crisis, with recovery only accelerating from 2013.

As a temporary solution, the government introduced the restructuring of public work and widened its possibilities from 2014. Public work schemes were in part designed to provide income to people in communities where there were no jobs. It was also intended to get people back to work who had been out of work for years or even decades. In addition to re-integration, the public work programme was extended to develop the participants’ employability skills—for example through training—to help them find work in the primary labour market after the programmes ended.

The government came under fire from the opposition because the number of public employees reached sky-high levels in the first few years. However, the secondary labour market offered much lower wages than the competitive sector, and the government also provided subsidies to help people move into the primary labour market. As a result, there are now fewer public workers than under the left-wing government, down to 65,000.

Targets for 2030

Our labour market indicators have not deteriorated during the period of the polycrisis that began with the 2020 pandemic, and in fact employment has grown steadily in recent years. We intend to maintain this trend in the coming years. The government has set a target of achieving an activity rate of 85 per cent for the 15–64 age group by 2030.

In 2023, the active population, i.e. the combined number of employed and unemployed, accounted for 78 per cent of those aged between 15 and 64. Last year, only Iceland and the Netherlands exceeded 85 per cent in Europe. Even with the number of people in this age group, currently at 6 million 158 thousand, decreasing, this target can only be achieved if the number of employed people increases by almost 300 thousand. This will require a much higher share of atypical employment, both for young people and for those with young children. In Hungary, only 4.1 per cent of the employed work part-time for less than 36 hours per week on average, which is the fourth lowest in the EU, although the proportion of people occasionally or regularly working from home has increased since the pandemic.

Quality Jobs, Highly Skilled Employees

To this day, the government is unfairly attacked for subsidizing assembly plants, i.e. low value-added, mainly industrial facilities, and thus increasing employment.

In reality, a significant share of new jobs after 2010 was created in the high-tech sector, i.e. in high-tech industries and knowledge-intensive services. This, of course, required highly qualified employees. The figures speak for themselves: in 2010, only 16.5 per cent of the workforce had a university degree. By 2023, this figure had risen to 25.1 per cent, meaning that more than a quarter of today’s workforce has a tertiary education.

Whereas in 2010 more than a quarter of the much smaller workforce had completed a maximum of eight years of primary education, the figure is now only 17.5 per cent, and only 1 per cent have not completed primary education.

We can state that we are no longer the country of assembly plants that we were before 2010. In 2022, 6.4 per cent of total employment was in the high-tech sector, the fifth highest in the EU.

It is to be hoped that this trend will continue, and that the gap between regions and social groups will continue to close over the decade ahead, while the gap between more developed countries with a more prosperous history and our own will continue to narrow.

Piroska Szalai is a labour market expert, a researcher at Economy and Competitiveness Research Institute of the Ludovika University of Public Service.

Kristóf Nagy and Mátyás Zsolt Varga are journalists at Mandiner.

Related articles: