The following is a translation of an article written by Emese Hulej, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

Once a pupil at the Baár-Madas Reformed Grammar School for Girls, Éva Kohner was a true lady, hailing from successful ancestors. But then came the war, flight, hiding, and emigration… And then the beginning of a new chapter on the banks of the Thames in London. Discover the story of the Baroness through the lens of Magyar Krónika!

Baroness Éva Kohner, whose eventful life story was unknown even to some of her colleagues, died in London three years ago at the age of ninety-eight. All they knew was that the professor was a woman of straightforward character, with an open mind and a good sense of humour, or, at most, that in addition to her love of arts, especially music, she was also a big football fan. Here in Hungary, few people know the name of Éva Kohner, but in professional circles, she is well known, as her work,

particularly her research on the effects of diabetes on the eye is internationally outstanding.

As a professor at the prestigious Hammersmith Hospital and Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, she was the head of several important research groups as well.

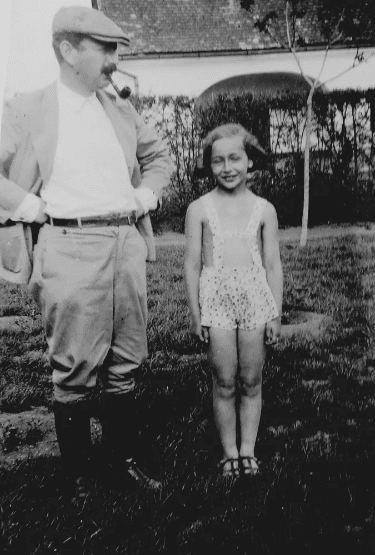

The young girl left the country in 1949 and took a portion of Hungarian soil with her to emigration in the small wooden box in which she had collected peanuts as a child. The soil was from Szászberek, because there, in a village near Szolnok, was the family’s property, a children’s paradise with a swimming pool and tennis courts. The family had a castle there and a prosperous model farm around it. It was little Éva’s real home, the Hungarian countryside, a place for long carriage rides, cycling, and happy summers when she could hide among the acacia trees with her favourite books.

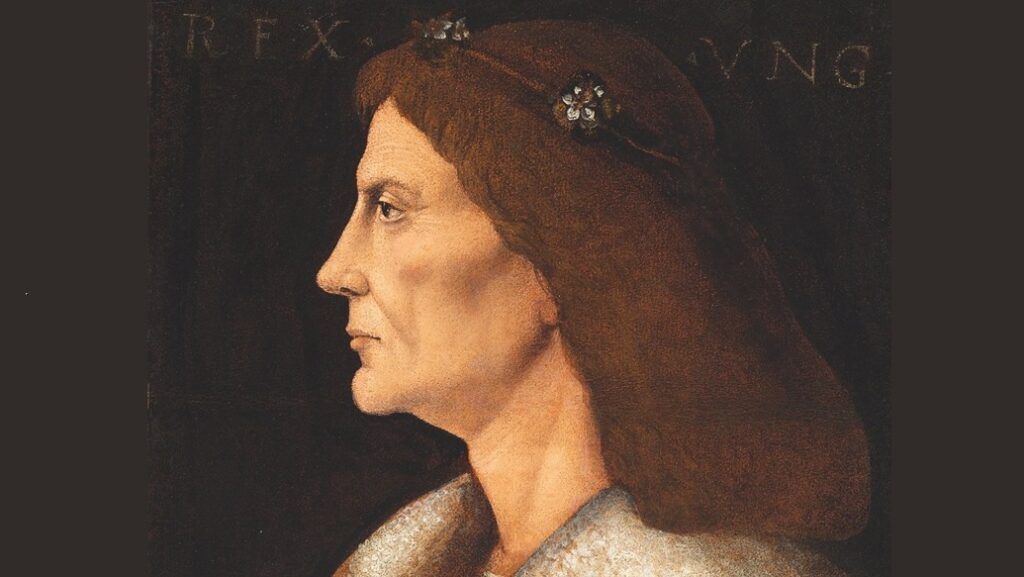

The family’s roots can be traced back to Náthán Mózes Kohner, who set off as a produce merchant from Leipzig to the Czech Republic and then to the Hungarian capital. His descendants took part in the building of the railways and were respected as citizens of ‘irreproachable character and decent behaviour’. Éva’s uncle, Adolf Kohner, became a member of the economic elite between the two world wars, was an art collector and art patron, and is considered one of the founders of the Szolnok Artists’ Colony. In addition to paintings by Goya, Courbet, Manet, Renoir, and Gauguin, his collection included three Munkácsy paintings as well, several landscapes by László Paál and the famous painting titled Pacsirta (Lark) by Pál Szinyei Merse.

As a patron, he supported painter Adolf Fényes, but also the Museum of Fine Arts itself, and was one of the first in the country to become an automobile owner. His family was one of the assimilated Hungarian Jewish families that became pillars of the economy and culture. They celebrated both Christmas and Easter, professing themselves to be true patriots and committed Hungarians. Franz Joseph offered the family a barony in 1913, which then took great care in raising the next generations. The family prospered, they invested in banking and industry, then bought land and established a model farm on it. They excelled at cattle, pig, and horse breeding, had a distillery, several mills, and a cannery, too. They were also given a noble first name: Szászbereki. In time, they built a beautiful Art Nouveau mansion, or rather a castle, on the estate.

The family’s Budapest base was in Kígyó Street, from where little Éva went to school. She had a kindly German nanny who loved the two Kohner girls and was devoted to the family, but one day she asked permission to go home and cast her vote for the Anschluss. Born in 1929, Éva Kohner was a student at the legendary Baár-Madas Reformed Grammar School for Girls, attended services at the Calvinist congregation of Pasarét, and was still on the confirmation list in 1943.

When Jews were required to wear a yellow badge, members of the Christian Jewish Association of converts were given white stars, including Eva, who was even secretary of the association for a time. But when the Germans occupied the country, the exemptions were no longer worth anything. Although even with a yellow badge, the young girl was not subjected to any atrocities at the Pasarét congregation of the charismatic pastor Sándor Joó, the family was soon forced into hiding. Éva’s father was taken away, a victim of the Holocaust, and then the post-war peace period which ended in nationalization also affected the family.

The young girl first emigrated to Vienna to escape the communists, and as a theatre enthusiast, she happily took a job in a ticket office, but soon moved on to London. She went to medical school in England, chose ophthalmology as her speciality, worked under renowned pharmacologist Colin Dollery, and had a distinguished career. Her publications on the effects of diabetes on the eye were well known to his Hungarian colleagues, too, but it was decades before she was able to return to Hungary for congresses. She also made it to her home village of Szászberek, where she was welcomed and tried to help the local community as much as she could.

It is a sad end and the irony of fate that

she, who had done so much for the sight of others, had to live the last period of her life almost blind.

She was suffering from macular degeneration, which probably prevented her from writing the story of her exciting and long life, full of twists and turns.

Read more about famous Hungarian women:

Click here to read the original article.