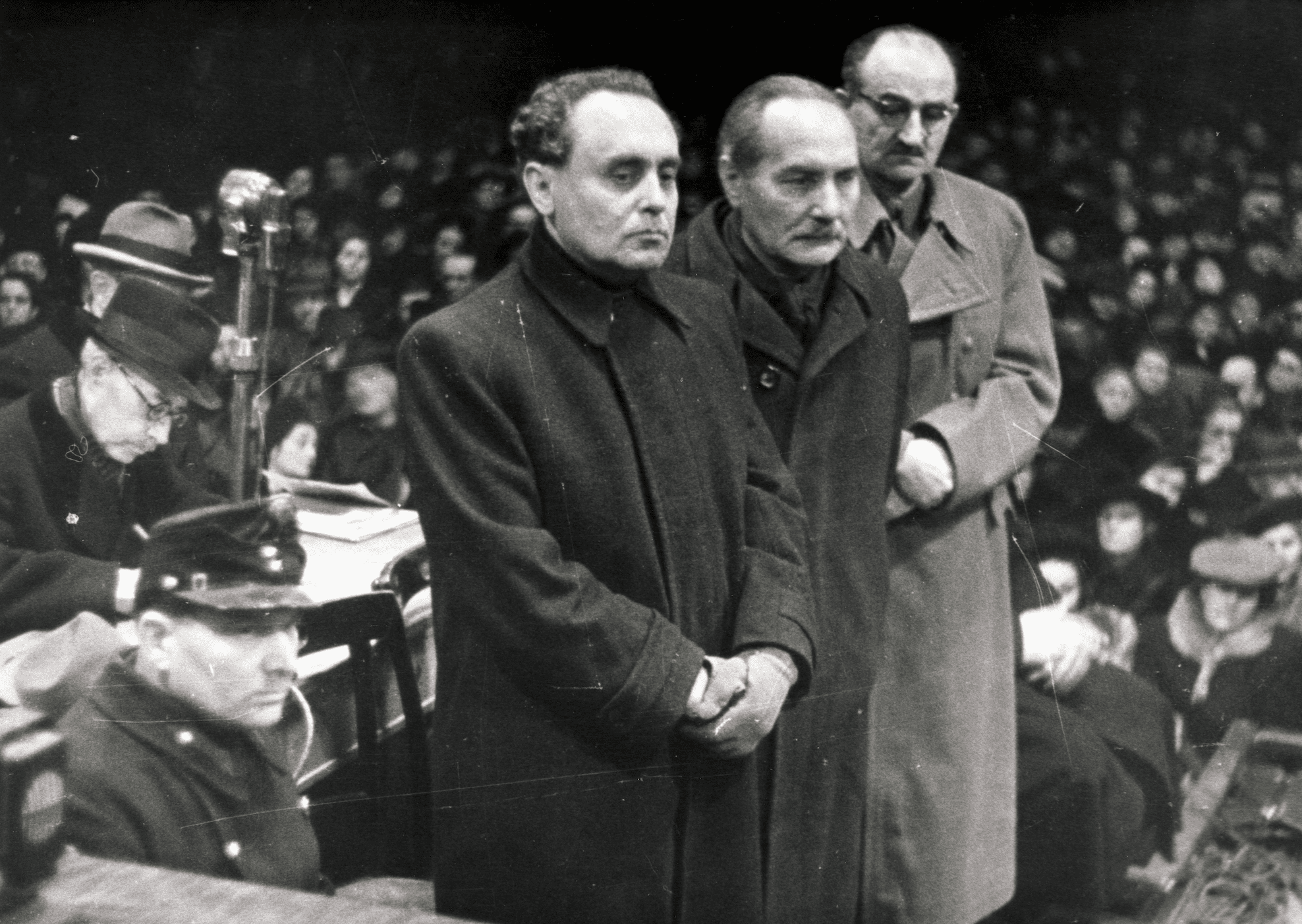

The sentencing of pro-Nazi or Arrow-Cross war criminals often served a political and historiographical agenda at the People’s Tribunals, albeit subtle and hidden. The mere terminology of the cases – such as the constant references to “fascism”, “German fascism” and “aristocratic (úri) fascism” – was a diversion that would set the course of Hungarian Communist historiography for the coming five decades: Nazi policies of nationalisation, property confiscation, the omnipotent state and deportation of minorities – all similarly present on the Soviet political program – were to be described as “fascistic” or “aristocratic”, and the term “socialist” was to be avoided in connection with Nazi supporters or Arrow-Cross policies. Such meetings of opinion could not always be evaded though: an amusing example was the case of Arrow-Cross dictator Ferenc Szálasi, who corrected the Communist judges’ misquotation of Karl Marx and who forced Communist prosecutor György Marosán to agree with his critique of Capitalism. On another occasion – and perhaps through a slip of tongue – the Communist prosecutor even admitted that Szálasi was correct in attacking Jewish bankers.[1]

Interwar Hungary saw a return of Habsburg-style liberalism in the 1920s, before slipping into a tenuous Axis alliance and seeing the Nazi occupation of the country in March 1944. The Sovietisation of Hungary demanded the discrediting of all liberal, democratic and capitalistic traditions as undesirable, and therefore a “straight line” had to be drawn from the white counter-revolution of 1919 to the 1944 October Arrow-Cross takeover, mashing together Horthy’s meagre starts in the rural city of Szeged with the last efforts of Arrow-Cross and German resistance in the Westernmost town of Sopronkőhida. The “straight line” between “Szeged and Sopronkőhida” (two important historical dates symbolised by geographical names) was an important point stressed by the People’s Tribunals through and through. Self-avowed radical revolutionaries – often with past left-wing careers, as in the case of Arrow-Cross journalist László Temesváry, ex-editor of a Socialist daily – were presented as “conservative”, “aristocratic” or “Capitalistic” “elements of subversion” during the trials, in spite of the loud protests of the accused, who, in fact, had dedicated most of their careers to fighting big land owners and “Jewish” banks.[2]

Interwar Hungary saw a return of Habsburg-style liberalism in the 1920s, before slipping into a tenuous Axis alliance and seeing the Nazi

PHOTO: FORTEPAN / BERKÓ PÁL

Special attention was given to Arrow-Cross henchman and later minister Emil Kovarcz, who, as a young cadet, took part in the 1920 murder of two Socialist journalists. The murder – which took part 26 years before the trial – could hardly be classified as a war crime, and People’s Tribunal judges have on other occasions declared that crimes that had happened during the 1919-1921 counter-revolution were outside of their jurisdiction.[3] This double murder was different though, as Admiral Miklós Horthy was supposedly the mastermind behind the killings: Kovarcz was pestered with long questions ranging across dozens of pages of court proceedings until he finally admitted that according to his vague memories, it was Admiral Horthy who gave the order for the murders more than the quarter of a century ago.[4] Another counter-revolutionary pogrom-monger, Ferenc Molnár had to admit that he and his friends nicknamed their clubs used for killings “Horthy-sticks”.[5] Such – often pathetic – efforts were made in order to prove Horthy’s guilt as the ex-governor had escaped into exile and could be blamed with little else than non-action during the Nazi invasion of the country and the Holocaust; as for the latter, deportation of Jews or assistance to it rarely formed a part of the accusations.

Between 1946 and 1948 around 200,000 Hungarians of German ancestry (Volksdeutsche or sváb in Hungarian) were deported from the country, following the guide of a large-scale Soviet plan of Eastern European population replacement.[6] Communist propaganda at the time was largely racist and anti-German, often accusing random Hungarians whose surname ended with the letter “r” of having had German forefathers (and consequently Nazi sympathies); Soviet movies and articles at the time made good use of the fact that the Hungarian word for cockroach (svábbogár) literally means “German bug”. Hungarian racial biologist Lajos Méhely’s court proceedings went underway at the time when anti-German rhetoric soared in the country; the Communist prosecutor consequently thought that Méhely’s writings – which sought to protect Hungarians of “pure racial ancestry” from mixing with Jews and Germans in order to preserve a clean blood-line – were a good reason to ease his sentence, as they testified to “his seething hatred of Germans” – an attribute which, according to the prosecutor, was “nice” and “democratic”.[7] In other cases, charges of “racism” and “spreading racial nonsense” were criminal charges – in this case, they were seen as a laudable “democratic” merit.

Hungarian political life in the interwar period was largely “national” in its rhetoric, with both liberals and radical right-wing politicians employing patriotic if not openly racist terminology

Hungarian political life in the interwar period was largely “national” in its rhetoric, with both liberals and radical right-wing politicians employing patriotic if not openly racist terminology. It is therefore difficult to make a clear distinction between political affiliations and groupings based purely on their self-identity: Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky, rescuer of Jews and a martyr of the anti-Nazi resistance called himself a “nationalist radical” just like most followers of the Arrow-Cross did. However, People’s Tribunals rarely bothered with such nuances and delicate distinctions; Hungarian nationalists, both anti-Nazi and pro-Nazi, faced trials alike. László Budaváry, a Catholic and a nationalist – but also a deadly enemy of the Arrow-Cross and author of one of the few known illegal pamphlets that called the attention of the populace to the horrible nature of deportations in 1944 – was tried for his racist newspaper articles; he protested in vain by citing one of his texts in which he wrote of Stalin as a ‘murderer, but one that at least hates the Jews’. There was certainly something comical about Budaváry citing his respect for Stalin’s anti-Semitism to defend himself; the court similarly found his arguments lacking and sentenced him to 10 years in prison.[8]

Trials launched against monarchists, steadfast conservatives and classical liberals served an even more unabashed resolve to rid the country of democratic opposition. István Friedrich, an ex-supporter of Habsburg emperor Charles IV’s return attempts to Hungary and a politician who was perhaps most well-known for having armed the country’s Jewish population during the 1918 pogroms out of Christian Zionist convictions, was arrested in 1951 and given 15 years in prison. The charges included his determination to return private property confiscated by the Communists, and a supposed attempt – barely detailed by the court – to restore the Habsburg Empire. Hugó Payr, a one-time wrestling champion and a devoted libertarian who often protested anti-Jewish legislation in the national assembly, was arrested with the same charges.[9] The Soviets had a more difficult time in dealing with Hungary’s greatest conservative statesman, the physically fragile, but iron-willed Count István Bethlen. Bethlen served as prime minister of Hungary between 1921 and 1931; his leadership brought economic prosperity and the repression of pogroms and left- and right-wing radicalism alike.[10] A strong and determined democrat with no far-right stains on his career posed an immediate threat to the emerging pro-Soviet dictatorship; thus, one night in April 1945 he was hauled off to a train to Moscow, never to be seen again. Though not immediately related to the People’s Tribunals, the way the largely Soviet-controlled authorities dealt with this politician – arguably the largest obstacle in the way of the Sovietisation of Hungary – symbolises the general direction of political developments in the country between 1945 and the utter Communist takeover of 1948.

Having looked at the trials of Arrow Cross men, radical right-wingers, ethnic Germans and Monarchists, the picture regarding the People’s Tribunals has not become much clearer. In fact, if these trials – separate in their conduct and themes, but largely same in their nature and outcome – could prove anything, then it is that the Soviet-style system granted only one sort of equality to its political opponents: equal misery and injustice before the law.

[1] Karsai László, Karsai Elek, ’A Szálasi-per [The Szálasi Case]’ Budapest: Reform, (1988), 101.; Szerencsés Károly, ’Az ítélet: halál. Magyar miniszterelnökök a bíróság előtt [Sentenced to Death. Hungarian PMs in the Court Room]’ Budapest: Kairosz, (2009), 337-338.

[2] See the cases of Ferenc Fiala, László Temesváry and Emil Kovarcz: Budapest Főváros Levéltár [Budapest Metropolitan Archives, from hereon: BFL], VII.5.e.1950.3919., 43-44.; XXV.1.a.1945.4832., 125-126.; XXV.1.a.1946.1494., 6.

[3] See for example the case of Franciscan friar István Zadravecz, during which the court proclaimed its reluctance to deal with a 1919 murder charge: Veszprémy László Bernát: ’”Ne hagyjátok őket elcipelni!” Zadravecz István és a holokauszt [„Do not let them be taken away!” Friar Stephen Zadravecz and the Holocaust]’, Sapientiana, 2016/1, 78-91.

[4] BFL, XXV.1.a.1946.1494, Kovarcz trial papers, 1-42., admission at 24.

[5] BFL, VII.5.e.1950.6785.00012, Ferenc Molnár and others’ trial papers, 12.

[6] Fehér István, ’A magyarországi németek kitelepítése 1945-1950 [Deportation of Hungarian Germans, 1945-1950]’ Budapest: Akadémiai, (1988)

[7] BFL, VII.5.e.1950.235.I.0165920, Lajos Méhely trial papers, 58., 80.

[8] BFL, XXV.1.a.1945.778.I.0121114, László Budaváry trial papers, 65-67., 23.

[9] BFL, XXV.60.e.0012201.1951, István Friedrich and Hugó Payr trial papers, 28., 48., 104.

[10] For an English language account of Bethlen’s life and politics, see: Romsics, Ignác, ‘István Bethlen: A Great Conservative Statesman of Hungary, 1874–1946’ New York: Columbia University Press, (1995)