In the first instalment of a series aiming to present different views on higher education, its past, present and future, through the lenses of scholars, we are publishing the brief commentary of the interviewer, Gábor Molnár, followed by his conversation with Calum T M Nicholson, Director of MCC’s Climate Institute. Dr Nicholson read social anthropology at Trinity College, Cambridge, and migration studies at St Antony’s College, Oxford, and completed his PhD in human geography. He researches the social consequences of climate change. Earlier he served as a development consultant and a researcher for the UK Parliament. At the University of Cambridge he has taught courses on international development, migration, the political aspects of climate change, and the impact of social media.

When choosing a BA, MA or PhD Course, even when deciding on majors and minors, students are faced with a decision. Round themselves or sharpen their edges? Nowadays, with heavy government support for highly specialized disciplines, the number of students choosing the latter is as high as ever. In a world where a career is a hassle, and not a privilege for most, we most consider if we want to further distance ourselves from the principle these institutions were founded on: the love and thirst for all knowledge.

Calum TM Nicholson is an advocate for seeing the whole. He thinks it’s important to question our assumptions. He realizes that an individual also contains a plurality of perspectives, not all of which are reconcilable, and that this isn’t a fault, but an irreducible feature, of being human. Our institutions, particularly educational ones, should work to accommodate this very human impulse, rather than suppress it.

***

After I had enough dots to connect, I came to the conclusion that Calum is sought after in academic circles not because of his answers but rather his questions.

I definitely have my topics where I’m a ‘proper’ expert. But the truth is, whenever I teach on anything, I try and teach in a way where there’s two levels to it. On the one hand, there’s the content of what we’re talking about, but the truth is students may not be that interested in the topic of climate or migration.

So, I always think ‘how can I present my work in such a way so that there’s something of value in it for all the students, regardless of their interests’? Even if you’re not interested in the subject matter that I’m talking about, I’m typically giving it only as an example to illustrate a broader point. I might, for instance, use ‘climate migration’ a case study to illustrate a way of thinking about problems in the world, and the problems with how we conceptualise our problems to begin with.

And so, the reason I can talk on a range of topics is

because it’s not really about being a subject specialist. It’s about asking the right questions, in the right order.

I usually use a given topic to try and draw attention to a way of looking at problems more generally, which you might then be able to apply to other problems, superficially unrelated to the one we’ve been discussing. One of the reasons I like giving different talks to the same audience is that eventually students start to pick up this way of thinking—of finding the general pattern across a range of particular cases.

Can you get by without ever answering?

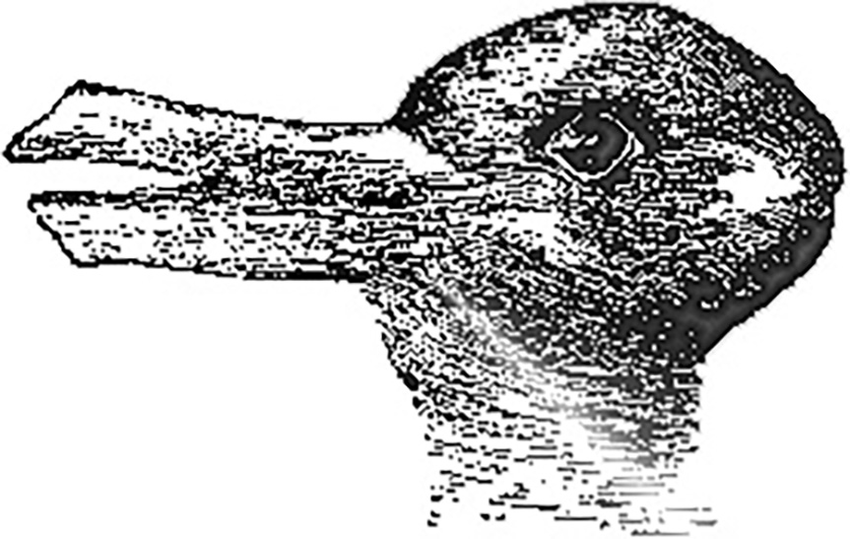

Well, there’s a difference between a fact and an answer…. It’s not that I’m not giving an answer to avoid taking a position—that’s not the point. My point is that there are almost always two ways of looking at a fact. This is best illustrated with the famous image of the ‘duck/rabbit’:

The fact is that there is an image. But whether it’s a duck or rabbit is down to how you interpret it. This the question of what we do with the facts, how we act on and with them, is quite subjective. Arguments can be made either way.

The problem we’re having today is I think we’re becoming a culture that’s increasingly obsessive about the factual, technical detail, and we’re losing that sense of the whole into which it fits. And the whole isn’t about facts. It’s about interpretation of facts. Ducks and rabbits. That isn’t a fault, but a feature, of being human.

Do you think that we can teach generalists on the same scale that we teach specialists nowadays with the same model, university or higher education?

So, it used to be that you went to university to be developed as a person.

It was an end in itself…meaning you were an end in yourself—not just an economic actor, but a citizen, a person, a human being.

But these days, it’s tricky because what has happened in the last forty years is that universities in general have started to be run on a neoliberal technocratic model. We only prize technical skills, or narrow forms of ‘expertise’. We have lost sight of the value of the generalist. I think we have a general problem in society now of having a culture that is not conducive to teaching people how to think in a general sense, nor to incentivize them to do it because most people are incentivized just to watch their own small patch.

Related articles: