In recent times, due to the tragic conflict between Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, there has been an increased interest in Eastern Slavic affairs in the West. The three formerly close countries are now engaged in a bloody war, and while most people still struggle to understand what led to this deadly conflict, the end of it is still nowhere on sight. Eastern Slavic nations’ history is not only of war, however. In fact, the history of the similarly Eastern Slavic Rusyns quite encouraging. The Rusyns, a tiny nation in the Carpathians, whose ancestral homeland is now spread across the territories of Ukraine, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland and Romania, have lived with Hungarians for over a thousand years, and although the relationship has not always been perfect, there is much to learn from the shared history of Hungarians and Rusyns about cooperation and tolerance.

Who Are the Rusyns?

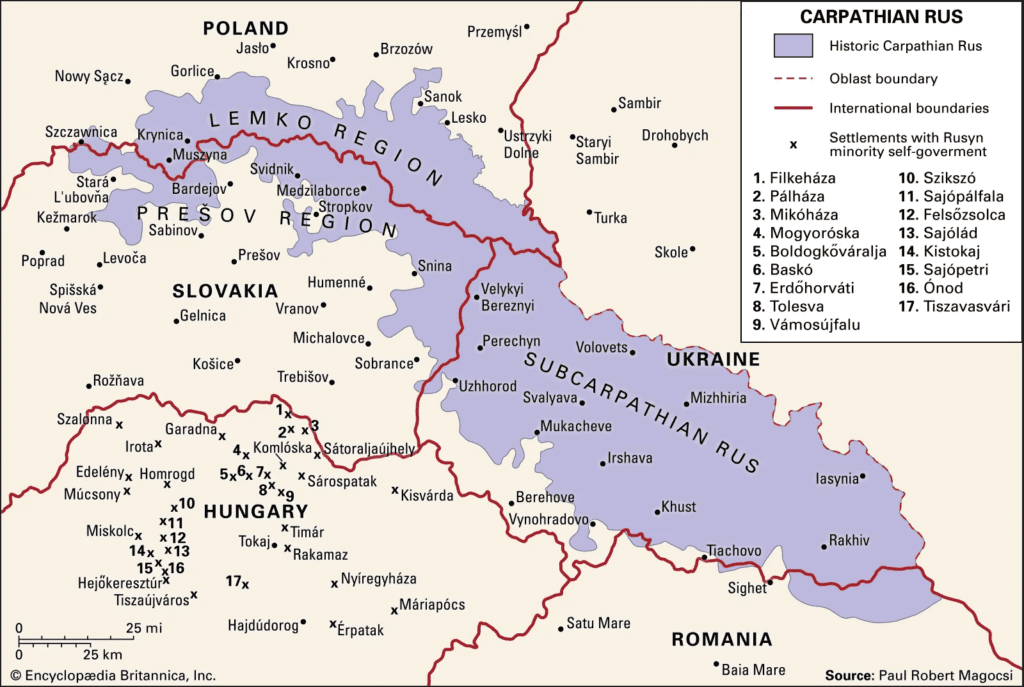

Rusyns, also known as Rusnaks or occasionally Ruthenians, speak an East Slavic language, treated either as a Carpathian mountainous dialect of Ukrainian or as a separate language with regional varieties. Initially an Eastern Orthodox ethnic group, Rusyns became religiously divided due to centuries of historical isolation, with both Eastern Orthodox, Catholic and Greek Catholic denominations being widely followed amongst Rusyns today. The Rusyns have lived at both sides of the Carpathian Mountains ever since eastern Slavic tribes arrived in the region between the 5th and 7th centuries.

Historically, the Rusyns lived in the mountainous regions of the Hungarian Kingdom, which significantly hindered their ability to communicate with some other parts of the realm. As a result of these restrictive geographical circumstances, multiple ethnic subgroups emerged within Rusyns. Boykos, Lemkos, Hutsuls and Dolinyans are the most well-known such subgroups. The root ‘Rus’ in the word ‘Rusyn’ ethnonym indicates the small nation’s shared origin with Russians. Despite the shared origin, the Rusyns, most likely, had never been part of any Slavic politeia until the 20th century—up until recently, Rusyns lived side by side with Hungarians.

For centuries, the shared history between the two nations was largely characterized by mutual cultural influence and exchange without the presence of forced ethnic assimilation. Elements of Hungarian culture have become integral parts of Rusyn traditions. For instance, Rusyns use the Hungarian terms gulyás, bogrács (cauldron) and leves (soup) spelt with Cyrillic letters when transcribed. The Rusyns folk costumes are similar to some Hungarian ones. In the picture below, the Hutsul man is wearing a garment strongly reminiscent of Hungarian folk attire. He even has a traditional Hungarian shepherd’s axe (fokos) in his hands.

To a high degree, the language of the Rusyns is mutually intelligible with other East Slavic languages. Nevertheless, the Hungarian linguistic influence is not limited to vocabulary that is associated with sharing the same administration, high culture and education with a dominant ethnic group that happens to speak a different language from the small minority. Instead, the Hungarian language’s influence on Rusyn can be widely observed—from the above-mentioned cuisine-related words to terms that have Slavic equivalents as well. These shared Rusyn-Hungarian words pronounced in the same way in both languages but spelt with different alphabets include ‘gift’ (Rusyn ‘ояндик’–Hungarian ‘ajándék’), ‘garden’ (‘керт’–‘kert’), ‘good’ (´йов´–‘jó´), ´hunter´ (´вадас´–‘vadász´), ´sure or indeed´ (´бiзувный´–‘bizony´). Else then these, many other Hungarian words, too, are used by Rusyns to describe a wide range of topics. In short, over the centuries, Hungarian words gradually made their way into the core of the Rusyn language, playing a significant part in the everyday communication of Rusyn people.

Peaceful Coexistence — A Shared Hungarian and Rusyn History

Important events in the Rusyn’s ethnogenesis are intricately connected to Hungarian history. Besides intermingling with the Hungarian population, Rusyns also played a role in the assimilation of the Cumans, who migrated to the Hungarian Kingdom from the great steppe seeking refuge from the Mongolian invasion. Béla IV provided Cumans with shelter, and they have since been a part of the Hungarian population, settling both in Transcarpathia and in the Great Plain. The presence of the Cumans explains the naming of numerous Hungarian locations with the word ‘kun’ in their toponyms: ‘kun’ in Hungarian means ‘Cuman’ (e.g., Kiskunság). The Rusyns also played a role in the re-population of southern Hungary, after it had been liberated from the Ottoman Rule. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Habsburg monarchy launched programs to recolonise the previously devastated lands, and as a result, hundreds of Rusyn families moved to Bács-Bodrog and Szerém Counties helping the revitalisation of these region. The descendants of these Rusyn settlers are still present in today’s Serbia and Croatia as a recognized minority.

Prior to the Austro-Hungarian compromise of 1867, Rusyns were assimilated into the Hungarian population only spontaneously. Mixed families were fluent in both languages, however, due to the dominance of the Hungarian language, children typically preferred to speak in Hungarian. A noteworthy figure who embodies the integration of Rusyns into Hungarian society is Károly Mészáros (1821–1890), a scholar and civil servant born into a Rusyn family from Ung County. In his autobiography, he wrote: ‘On account of my birth, upbringing, and political persuasion, I am Hungarian to such an extent that I do not know a single word in Russian or Slavic; however, because…I am a member of the Greek Catholic Church, and because I live among Russians (Editor’s note: Rusyns were called Russians at the time in Hungary), I am familiar with and appreciate the needs and legitimate wants of these people.’

Mészáros’ story is not unique among Rusyns. Other prominent Rusyns, such as Demeter Kerekes, the Greek-Catholic priest of Hajdúdorog, also experienced a similar integration process. He was described as someone who ‘did not know Russian well, as is usual with Greek Catholic priests in the Plain, what is more, he was proud to be a Hungarian—while at the same time being greatly attached to the Greek Russian religious rites…due to their special poetic character.’ As demonstrated by these examples, while assimilation did happen gradually, overall, the two nations lived side by side peacefully without the smaller nation being forced to use the larger nation’s language.

The way in which Rusyns, along with many other nationalities, integrated into Hungary in the past provides a model for other nations on how to successfully live together with members of different ethnic groups. This integration process involves creating opportunities for education, cultural exchange, job placement, and infrastructure development. These so-called soft power mechanisms encouraged people like Mészáros to identify as Hungarian nationals while retaining their ethnic roots and religion. By following this approach, multi-ethnic countries could benefit from the unique talents of individuals from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

While overall, Rusyn–Hungarian coexistence was successful and peaceful, there were episodes in Hungarian history, too, when the relationship was not ideal. For instance, the Lex Apponyi of 1907, along with some other legislation adopted after the Austro-Hungarian compromise, hindered the development of Rusyn education in the Kingdom of Hungary. Although hardly due to ethnicity-based discrimination, in the 19th century certain economic hardships led some Rusyns to seek fortune abroad, eventually creating a significant Rusyn diaspora in the USA. Furthermore, due to the Trianon treaty and the political turmoil of the 20th century, Hungary and Rusyn heartlands eventually ended up being separated from each other. In a tumultuous hundred years, before finally becoming part of Ukraine, the Rusyn-inhabited region of Transcarpathia was controlled by at least four different states: Austria-Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the USSR. These drastic political changes led to local Rusyns jokingly remarking about how to travel to five different countries without ever leaving their village.

Today, the Rusyns, similarly to other ethnic groups, have their own national self-government, and receive regular financial contributions from the central government. Hungary continues to create opportunities for the prosperity of Rusyns abroad as well. The Hungarian government invests significantly in the Transcarpathian region, where Rusyns, Hungarians and Ukrainians alike benefit from Hungarian government support.

Cooperation Instead of Restrictions of Minority Rights

As opposed to the unfounded accusations of xenophobia and anti-migration sentiments, Hungary has a long history of successful integration of other ethnic groups. The example of Rusyns shows that Hungary has essentially been successful in peacefully integrating other nationalities while allowing them to preserve their sub-identity. It’s important to note Hungary greatly benefited from the coexistence and cooperation with Rusyns and other Slavs. For example, more than 20 per cent of the Hungarian language and terminology that was once alien to the newly arrived Magyar nomads was adopted after meeting and collaborating with Carpathian Slavs.

Instead of trying to assimilate millions of foreign individuals that are impossible to integrate, Hungary created soft power mechanisms that accommodated Hungarians and non-Hungarians alike, fostering collaboration on the basis of mutual benefits, not abstract ideology of diversity for the sake of diversity. Integration and assimilation in Hungary has happened more efficiently and more smoothly than in countries where external attributes of foreign groups are banned or where minority language rights are violated. If a country creates an attractive culture, develops as a powerful civilizational hub, builds infrastructure, invites workers whose skills are valuable, and simply creates a nice place to live in, no restrictive measures of forceful assimilation are needed — integration and loyalty to the state develop spontaneously.